Distinguished Critique: Shazam!: Origins Review

This origin story neatly establishes a young hero's personality and motivations, even if some characters and concepts feel limited

—by Nathan on September 20, 2023—

His history fraught with tenuous legal battles and name changes, the DC superhero known as Shazam (once a Fawcett Comics character called Captain Marvel who couldn't use that name after DC's greatest rival adopted it for their own superhero) is one of the more famous Superman pastiches known to readers. I am not up on the character’s complete history, both within the comics and the industry which created and fought over his name, but I recently jumped at the chance to explore his New 52-era origins.

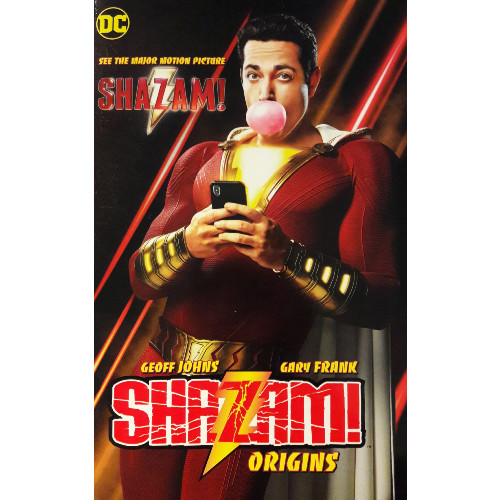

This Geoff Johns/Gary Frank (the duo behind Batman: Earth One, Doomsday Clock and Superman: Secret Origin) production retells a tale as old as 1940; the origin has been retold by the likes of Roy Thomas and Jerry Ordway, but with Johns and Frank’s tale, Shazam (no longer called "Captain Marvel") enters a new DC Universe with a new background, new characters, and a new emphasis on growth. Fans of the 2019 film with Zachary Levi may just want to take a glimpse at this tale, which serves as the inspiration and foundation for the movie.

Shazam!: Origins

Writer: Geoff Johns

Penciler: Gary Frank

Colorist: Brad Anderson

Letterers: Nick J. Napolitano and Dezi Sienty

Issues: Justice League #0 and #21, stories from Justice League #7-11, #14-16, #18-20

Publication Dates: May 2012-September 2012, November 2012, January 2013-March 2013, May 2013-August 2013

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

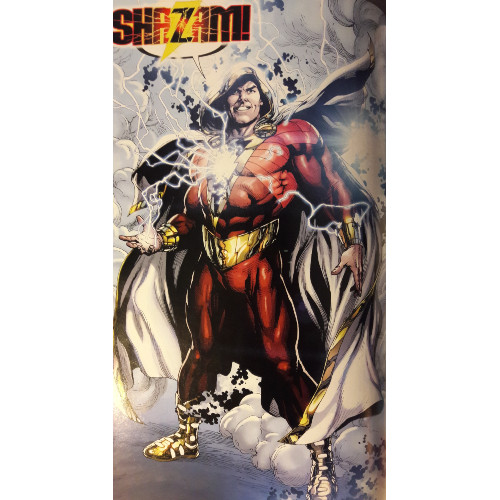

I am sure the Billy Batson of other-era Shazam comics is a nice kid. I am certain he’s deserving of the power which the wizard Shazam (yes, same name, two different characters) bestows upon him, granting him the combined powers and talents of mythical/biblical figures Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles, and Mercury. Having never delved into prior origin tales, I am uncertain how other writers characterized Billy prior to his run-in with the wizard.

Johns and Frank’s take on Billy is a tad rougher, a concept the movie played with as well. This New 52 Billy is an orphan and a bit of a punk. He runs away from foster homes, derides his case worker, and acts snobbish and rude to a new family whose home he joins as the narrative begins. "We’re not family," he tells the assembled foster kids. From the get-go, Johns and Frank seem interested in making their protagonist unique.

The decision aids them as the series progresses, particularly when Billy is confronted by the wizard Shazam. Seeing in Billy the embers of goodness and the potential for improvement, the wizard gives Billy his abilities…not because of a deep-seated sense of goodness but because he believes in the hero Billy may one day become. Again, I am not certain if this a deviation from prior source material–was Billy a better kid in earlier stories? Was he more worthy of the mantle of (previously) "Captain Marvel" and the powers of the wizard? What Johns and Frank do is set the boy up for transformation and spend a good chunk of the narrative exploring how Billy grows accustomed to and utilizes his newfound abilities. Can this unlikable, ungrateful kid really become a genuine, selfless superhero?

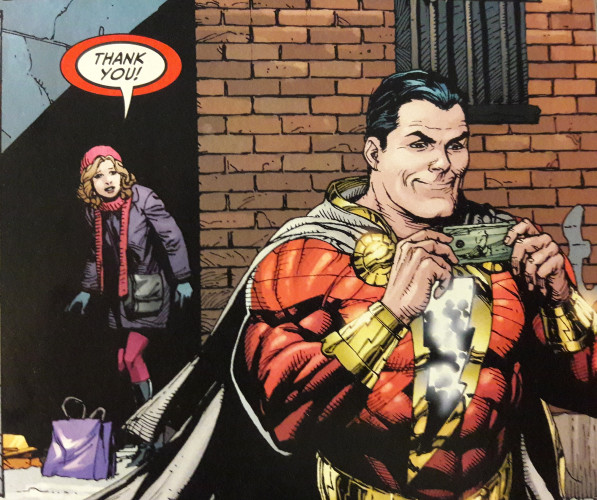

Like the film, the comic wonderfully explores how a young kid would first use his abilities. Billy and partner-in-crime Freddy Freeman run amok through Philadelphia, flying through the city, busting ATMs, planning on buying beer, and stopping the occasional crime (one of which they get paid for in return, and the boys start seeing the "crime busting" gig as a financial investment). Yet Johns balances Billy’s newfound joy and freedom in his abilities with the boy's attempts to fan the previously-established "embers of goodness" into a larger flame "I just don’t like bullies," Billy tells his new foster siblings after saving them from a couple punks, echoing both Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's classic "With great power..." mantra and Mark Grayson's philosophy in Invincible. It's a simple statement from the mouth of a child, yet it carries a powerful core which guides his actions as an adult superhero. "Bullies" aren't just the punks who shove you into lockers; they're also the jerks who connive against others, murder, cause all manner of havoc against an unsuspecting public. This leads Billy to become Shazam even when he gains no notoriety or compensation for his actions. The arc works well, giving Billy an opportunity to transform internally whenever he does externally.

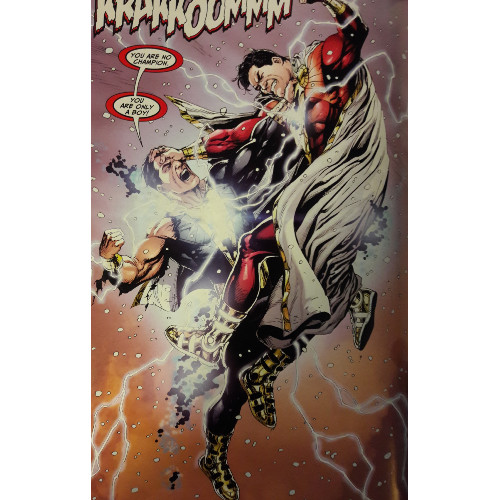

Johns interestingly parallels Billy’s journey with that of Black Adam, freed by scientist Doctor Sivana. Unlike the DCEU, which introduced Sivana as Shazam!’s primary antagonist and saved Black Adam for his own Dwayne Johnson-led release, the comic narrative dives straight into the Adam/Shazam conflict. Sivana is merely a conduit for which their enmity flows, and though he himself receives some magical abilities, he gains no powers. Adam is shown as an opposite to Shazam–an adult with incredible abilities who actually uses them to try and alter the world…but a world he wishes reshaped in his own image. While Billy learns to use his abilities heroically, Adam storms right out the gate, full of bravado, pomp, and a dark eye towards a world that has grown corrupt and fetid.

Like Billy, Adam is a creature guided by morals, surprisingly. These morals are just backed by vicious actions, such as when Adam drops a corrupt businessman to his death. Engagingly, Johns peers back through the centuries, examining Adam’s own origins for where his sense of right and the abusive use of his powers come from and offering a neat glimpse into the villain’s backstory (even introducing a decent twist which makes Adam all the more despicable). "You will see what I will do to free this world from those who enslave it," he tells Billy. In his own eyes, Adam is the champion Billy will never become–he strikes vengefully, decisively, assured in his abilities and the mission he follows. He’s less a villain and more of an anti-hero, Billy’s equal (if not better) in power but opposite in motivations and character.

Fans of the DCEU film may be curious to see where this story and the film divide; despite inspiring the movie, Johns and Frank’s narrative deviates in certain places…and, oddly enough, I praise the film’s creative choices in changing some stuff around.

For example, nowhere does the comic narrative discuss Billy’s parents–he’s simply an orphan, a lost kid in need of a home (despite how emphatically he rejects the concept). The movie chooses to paint Billy as abandoned, with his quest to track down his mom an engaging subplot which drives the character as well as establishes a deeper relationship with his foster siblings. The "abandoned" plot point also does a lot to explain why Billy behaves the way he does–in the comic, Johns simply makes him a brat, snotty because that’s just how Billy is. Perhaps the implication is that years of being jostled through the foster system have upended Billy’s sense of the world, but that’s honestly my opinion.

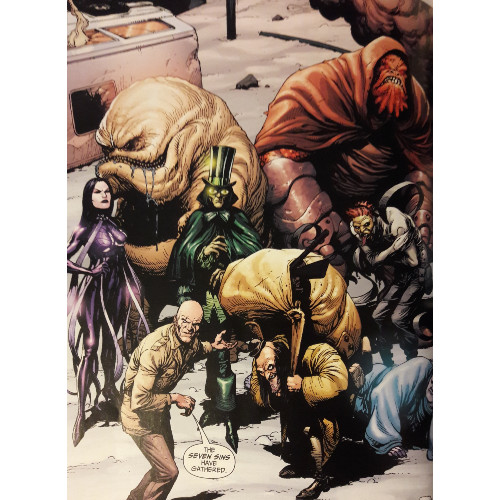

In the film, the Seven Deadly Sins are used more intriguingly than in the series. Johns spends a decent amount of time diving into Black Adam and Sivana’s own quest to wake each of the Sins. Yet, despite wonderful character designs thanks to Frank’s illustrations and Brad Anderson’s diverse color palette, none of the Sins stand out beyond their cosmetic appeal. The film, at least, attempts to make the Sins unique and allow them some decent weight as antagonists. Johns does little with them, bringing them all together near the end to possess a crummy character and transform him into the New 52 version of Sabbac, a demonic villain this writer wasn’t even aware of until after reading the story. I am sure the Sins have been used well in the time since, but their potential feels limited in Johns and Frank’s narrative.

This origin story was included as a series of back-up strips in several issues of the New 52 Justice League series, plus two whole issues of that series–perhaps this is why certain elements don’t feel quite as developed. Regardless, Shazam!: Origins still carries the weight and action of a well-told limited series. There’s a lot of heart that Frank and Johns both put into the narrative, and the focus of the whole piece is clearly Billy and his personal redemption, transforming into a true superhero, inside and out. Around Shazam is constructed a new world, with an old mythology reconstructed and fit into the gaps. A blend of old and new flits through the story nicely, making Shazam’s updated origins by and large a treat for DC newcomers and, hopefully, fans of the earlier Shazam stories I’ve not had the chance to peruse.