Random Reviews: Maus

A singular accomplishment, Maus uniquely, poignantly shares a narrative which history should never forget

—by Nathan on June 15, 2024—

Approximately six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust by Nazi Germany. That number doesn't even take into account the other people–including gypsies, Poles, war prisoners, and people with disabilities–whose lives were stolen. Shot. Starved. Gassed. Burned. The sheer horror of the event cannot be adequately described by the numbers alone.

A very recent survey found that over 245,000 survivors still live in over 90 countries, approximately half of that number in Israel, with the oldest survivors at 112 years old. Nearly 80 years after the end of World War II, men and women live as reminders of the Holocaust, each with a story of what they endured.

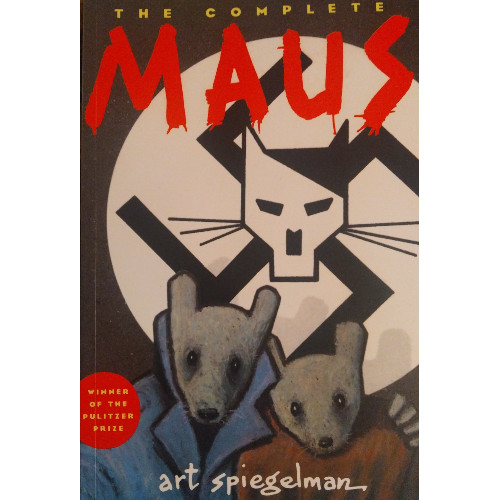

In 1980, American cartoonist Art Spiegelman began publishing, chapter by chapter, his literary magnum opus in the pages of Raw, a comics anthology published by Spiegelman and his wife over 11 years. Maus was eventually collected in trade paperback form and still circulates quite heavily today. I picked up a "Complete" edition from Amazon a while back and, in an effort to examine more graphic narratives from the early 80s, finally took a few weeks to give it a read.

I cannot, within this review, fully express the scope or the ever-present historical impact of the Holocaust, nor will I try to. It's my hope for this to only serve as a recommendation for anyone who wants to read the story of a survivor representing all those others who survived and maintaining the memory of those six million who did not.

Maus

Writer: Art Spiegelman

Penciler: Art Spiegelman

Inker: Art Spiegelman

Letterer: Art Spiegelman

Issues: Raw (vol. 1) #2-(vol. 2) #3

Volume Publication Date: October 2003

Issue Publication Dates: 1980-1991 (intermittently)

Publisher: Raw (issues), Penguin Books (collected edition)

On an interior page of the first volume of Maus, right before Chapter 1 begins, Art Spiegelman quotes a somewhat surprising individual: Adolf Hitler, the dictatorial leader of Nazi Germany. "The Jews are undoubtedly a race," the Fuhrer concedes, "but they are not human." Such a statement justified a litany of atrocities, but one can also see how Spiegelman was, also surprisingly, inspired by the claim. For the Jews represented in Maus are not human either. They are mice. Likewise, the Germans are cats, the Poles pigs, the Americans dogs, and the French frogs.

When I encountered my first image of Maus, in the pages of the 2004 edition of the Warman's Comic Book Field Guide (a strangely specific source, I know), I noticed that dichotomy immediately: cats and mice are often depicted as mortal enemies, with cats preying on the little rodents. The parallelism between this predator/prey relationship in the animal kingdom and the horrors of World War II made sense, primarily from a creative standpoint. It's only while reading Maus that I've come to understand the deeper picture, and that quote from Hitler puts the whole thing in the proper perspective. Spiegelman treats his primary subjects as the very rodents the Nazis saw them as, fashioning them as objects of disgust and as subhuman, worthy only of chasing, hunting, maiming, and killing.

Our house has had problems with mice lately, and my dad has set several traps for the little critters. The bait was set, a mouse would approach, the trap would snap down on its neck, and my dad would discard the corpse like we do all our household refuse: in a big, plastic bin, to sit and wait and rot until the garbage disposal folks hauled it away with the rest of the trash. By depicting the Jews in a similar fashion, Spiegelman turns the tables on us: we see them as the Nazis see them–or, we see them as "Nazi cats" would see them–and we are tasked with cultivating the sympathy necessary to hope these mice survive. Push aside your prejudices against actual mice and find the humanity in the characters Spiegelman portrays as other than human.

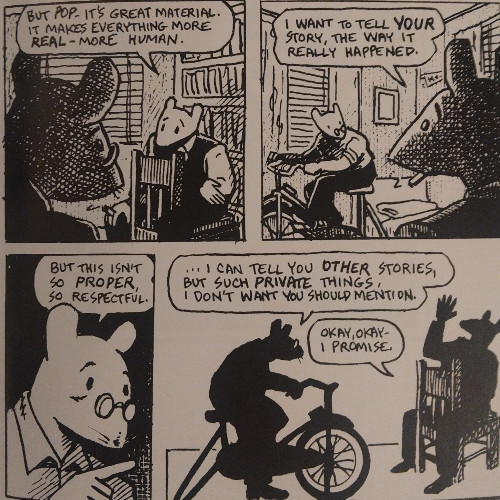

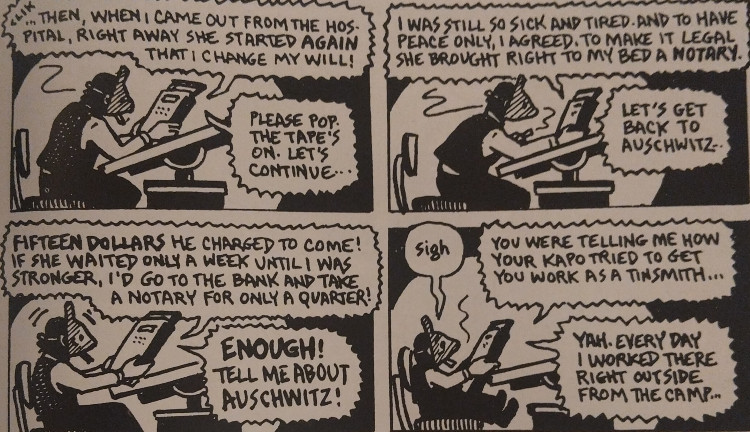

With this imagery forming the visual hierarchy of characters, Spiegelman develops a two-pronged story. I was fully unaware, reading Maus approximately fifteen years after first learning of it, that Spiegleman creates a frame tale around the Holocaust. Spiegelman himself, cast as a mouse, spends a good chunk of the graphic novel interviewing his father, Vladek, about his and his family's experiences during the war. Set in the narrative's version of the present, these scenes are just as potent as the flashbacks and constitute more than just Spiegelman sitting across from Vladek with a tape recorder. Spiegelman is asked at points to visit and help his father and his second wife (whom Valdek married in the wake of his first's wife suicide), also a Holocaust survivor. The men take walks, go on errands, make one hectic flight from Florida when Vladek encounters some health issues. Spiegelman's own journey is far less treacherous than his father's experiences, but the story of his relationship with Vladek is just as important as Vladek's personal narrative.

"A Survivor’s Tale," the book's subtitle reads, and that notion of surviving, particularly against increasingly incredible odds, drives Vladek's story. The lengths to which Vladek goes to protect himself and his family not only before World War II but during his internment are incredible–the ruses he must keep, the sacrifices he must make, the risks he must take, all to survive another day. Vladek is logical yet not without emotion towards his fellow man, cunning yet not ruthlessly cruel, and Spiegelman goes to great lengths himself to also depict that Vladek, for all his cunning, could not have survived without several people he interacted with and connections he formed. Polish friends, fellow Jews, even a German guard who sees Vladek's worth as a prisoner beyond his Jewishness, all aid in keeping Vladek alive. Vladek and his family take extraordinary risks but so do so many others.

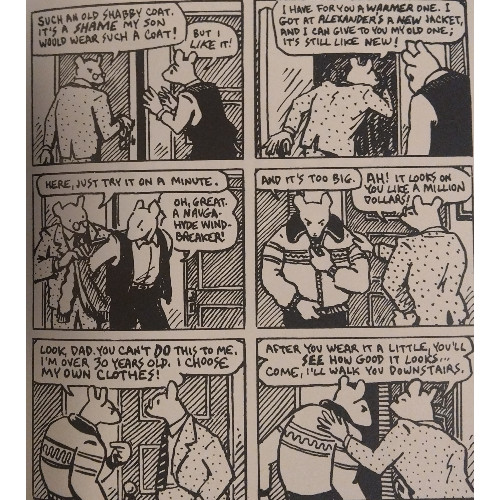

The Vladek we meet in the present is paranoid, brusque, and set in his ways (especially in some ways which–and more on this later–feel incongruent when considering his experiences); he's demanding of Spiegelman, fails to comprehend certain logical notions, follows specific routines, and transforms trivialities into trials. At moments, Spiegelman or another character questions whether Vladek's current attitudes and personality were impacted directly by the Holocaust, but Spiegelman leaves the answers uncertain. It's the reader who must attempt to trace the parallels–does Vladek discard his son's old coat without asking permission first because he knows of the discomfort of threadbare clothing? Does he meticulously count his pills as a result of always double checking his possessions while suffering in an environment where theft was commonplace?

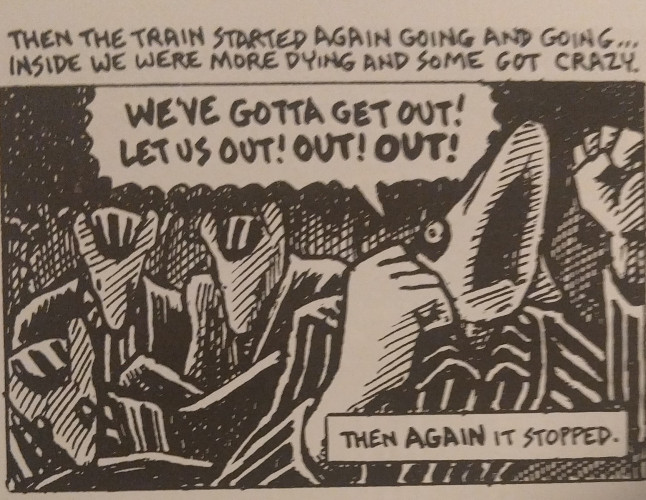

The cunning, logical Vladek is largely gone, and it's these contrasting qualities which help make the frame tale (tail?) as resonant as the flashback sequences. How did the Vladek who risked everything to save the lives of himself and his wife, who had to step amongst corpses to move about his confines, who spent miserable days among the dying in freight cars, who humbled himself further before those who already possessed an indomitable superiority complex, transform into the Vladek who drives his son and second wife crazy with his fastidious natures and routines? The man refuses to use matches to make certain he doesn't need to buy a new box. He disapproves of Spiegelman and his wife's decision to pick up an African American hitchhiker, reducing the man's race to a Jewish slur and assigning him the characteristic of "thief" because of some poor past experiences. When it's pointed out to Valdek that he, of all people, should be more understanding and tolerant of someone from a different ethnic background, he rebuffs the notion. How are we to reconcile these figures? And, again, can all of it be blamed on his experiences during the Holocaust? Likewise, when considering his wife, how much of her death can be attributed to her experiences?

This is the wrestling that Spiegelman, the "character," does under the pen of Spiegelman, the "writer." He's haunted by the loss of his mother, her specter hovering over the narrative as a voice lost, unable to share her side of the story. At moments, Spiegelman shouts at his father, demanding he not become distracted and return to the narrative he's telling. He hangs his head and wonders why, why, does Vladek behave this way? He insists he can buy Vladek a box of matches if he needs a new one, for cryin' out loud! There is a gulf between these mouse-men, one born not only of generational differences but vast experiential differences. Yet the moments of anger and shouting are matched with quieter sequences of reflection–Spiegelman, listening to a recorded conversation between himself and his father, jumps at a point where he raises his voice at Vladek to steer him back on track. He sighs, momentarily ashamed at his conduct. Spiegelman's narrative is not only a way of preserving his parents' story but of coming to terms with the horrors they endured, of coming to a point where he sees the world through his father's eyes and, just maybe, better understands the reasons Vladek views reality so differently.

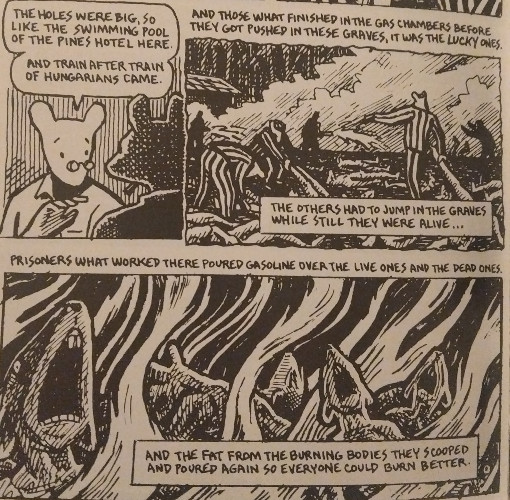

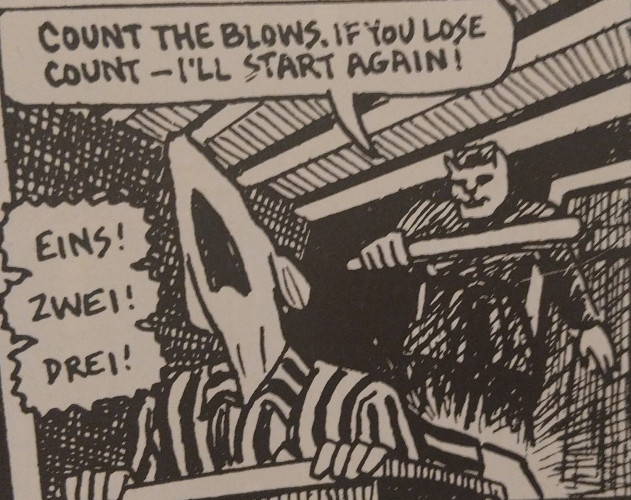

Maus doesn't shy away from the horrors of the Holocaust–we witness the agony of internment, the hopelessness behind begging eyes, the deaths from fire and bullets, the removal of identity (adding another layer to the "Jews as mice" imagery Spiegelman creates as you watch the Nazis further dehumanize individuals who aren't even portrayed as human). The animal characters add a thin layer of disconnect, but that provides a challenge, forcing you to constantly remember this is based on actual events and that if you begin turning your brain off at the sight of another mouse dying another horrible death, you have become complicit in the very reductionism Spiegelman challenges. Not every mouse is given a name or personality, but each mouse represents one of the six million dead. Each mouse embodies someone who was systematically terminated because they were decreed to be problematic, different, inferior, inhuman. I say this because I found myself slipping at moments and had to make myself look past the cartoon-esque style of art presented in Maus to absorb the reality beneath the ink and pen strokes.

To call Spiegelman's style "simplistic" would also mis-label and misinterpret his efforts. Spiegelman's art–kept to penciled and inked lines, without a splash of color–certainly feels aligned with the rise of black-and-white independently published comics, of which the 80s were a hotbed (look at Love and Rockets, Flaming Carrot, Nexus, the original Teenage Mutant Turtle Ninja issues). The lack of color encourages the reader to imagine the color, to weave in the red-hot anger of racist Nazi soldiers or the orange of flickering flames. You hone in on the details, observing how Spiegelman wrenches emotions from faces, both defiant and fear-filled. You note the seeming homogeneity amongst the mice when they're forced to wear their standard-issue concentration camp clothes, visually reinforcing the removal of identity and reduction of humanity. There's no color to see if one mouse is white while another is brown or black.

To reach the end of Maus and breathe a sigh of relief once Vladek is safely home from his horrific ordeal does little justice to the material. In the final panel, present-day Vladek has a slip of the tongue, calling a character by the name of a deceased loved one lost during the Holocaust. Spiegelman finished his father's story, but he subtly notes Vladek's story never really ended…not until, perhaps, the day he died in 1982, while Spiegelman was actively publishing Maus. The events are over, but the effect lingers. Spiegelman's mother is gone, along with her diaries, but her story doesn't end with her death, not when Spiegelman himself must grapple with the aftermath. Perhaps not all of Vladek's mannerisms and foibles can be traced back to the trauma he endured, but we can perceive the lingering impact of the Holocaust on his life. Yes, Vladek survived, but not every part of him made it through. Thus, Maus ends with a mixture of relief, celebration, and melancholy. We can take joy in Vladek's survival while sympathizing with his present troubles.

In 1992, Maus won a Pulitzer Prize, the first ever won by a graphic novel. As a singular narrative painstakingly detailing the efforts of one man straining to make it out of hell alive and his son's efforts to understand that hell, Maus deserves its accolades. Read this to better understand the Holocaust, yes, but read it also to understand the generational impact of such an event and how the stories of those who died and lived did not end with their deaths or when Jewish prisoners were liberated at the end of World War II. Vladek's is only one story out of literally millions but how Spiegelman presents it through this unique medium reinforces how complex and emotionally stirring Vladek's story is. During one scene, Speigelman wonders if detailing his father's narrative in comics form is appropriate; the critical reception of Maus over the last forty-plus years can lay his fears to rest, giving his father, his family, and millions of Jews a lasting legacy that defies the efforts made eighty years ago to erase them from existence and memory.