(Strand)om Stories: Black Panther Epic Collection: Panther’s Rage Review

While it gets off to a slow start, this Epic Collection provides a mostly compelling examination of the Black Panther's earliest adventures

—by Nathan on February 7, 2021—

Of all the heroes in the Marvel Universe, Black Panther was never a character who appealed to me until recently. As in, the last year or so. I knew who he was and was aware of some of his history, I had seen the Black Panther film starring the lamented late Chadwick Boseman a few times (as well as his other appearances in the MCU), but I was never really drawn to the character. Shortly after Black Panther was released, I took a stab at reading Christopher Priest’s late-90s/early-00s run on the character, but stopped shortly after starting. I can’t quite remember why. I may have grown bored, or I may have found more entertaining tales. I suspect the latter.

Earlier this year, I found some time (thanks, COVID-related shutdowns) to try Priest’s run again, and lo and behold, I enjoyed it much more. I read the entire thing, and I’ve since purchased the run in the hopes of reading it again. I loved Priest’s characterization and his handling of the world. Yet, I admit, I found myself rather lost at moments where I was unfamiliar with T’Challa’s history. So I decided to give some older tales a shot.

Fortunately, Marvel has collected some of the Panther’s earliest stories in their magnificent Epic Collection line. Two volumes have been published so far for the Wakandan king (with another one planned to release in about a month), meaning I had the ability to reach into the past and examine Panther’s first forays into herodom. Looking at the volume as a whole, how do those first stories shape the character and influence who he is today?

Black Panther Epic Collection: Panther’s Rage

Writers: Stan Lee, Don McGregor

Pencilers: Rich Buckler, Billy Graham, Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Keith Pollard

Issues Collected: Fantastic Four #52-53, Jungle Action #6-24

Volume Publication Date: March 2019

Issue Publication Dates: July 1966-August 1966; September 1973-November 1976

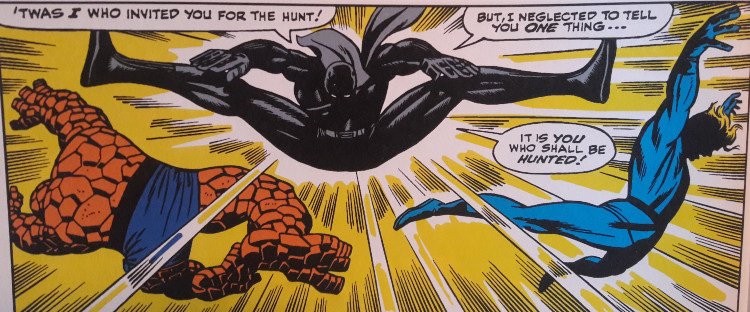

I have heard some consider Lee and Kirby’s original two-part introduction of the Black Panther, as seen in their Fantastic Four series, as “almost unreadable.” Undoubtedly, this has to do not only with T’Challa’s portrayal but also the racial stereotypes presented in the creators’ depiction of his African homeland of Wakanda. Some of this is certainly true, but I’ll straight up admit that I feel unable to comment or critique how Lee and Kirby (and, later on, McGregor) accurately or inaccurately portrayed their subject matter. At moments, Wakandan society does feel a little off (a valid complaint is how some parts of Wakanda are technologically magnificent while others are rooted in poverty), but I never got the feeling that Lee or McGregor turned up their noses at the characters or their world. Perhaps there isn’t the best understanding of how an actual, African society or kingdom would function, but the portrayal doesn’t necessarily come across as intentionally disparaging or damaging.

McGregor, specifically, adds a lot of depth to Wakanda in the pages of Jungle Action. Under Lee and Kirby, Wakanda exists only as a backdrop for their two-part FF story; when McGregor steps in, the kingdom flourishes. Diagrams depict T’Challa’s opulent palace, and a much-needed map details the boundaries of the country. Over the course of his twelve-part epic, “Panther’s Rage,” McGregor takes T’Challa from his palatial surroundings to the heights of snow-capped mountains and back down to the dredges of an eerie swamp. Wherever T’Challa roams, danger follows close behind, and not just in the form of enemies. McGregor showcases a world teeming with life, from serpents to white apes, to rhinos and crocodiles, and perhaps oddest of all, dinosaurs. That’s right, friends: the Black Panther successfully fights off a hungry T-Rex at one point. Heck, his archenemy Killmonger’s plan centers on the colossal prehistoric beasts. In climate and creatures, Wakanda is diverse. Understandably, the Jurassic Park elements feel a tad out of place; though intended to make Wakanda unique as a country, rampaging dinos instead turn the African kingdom into a quasi-Savage Land. The introduction of dinosaurs is a “jump the shark” kind of moment that feels more jarring than inventive.

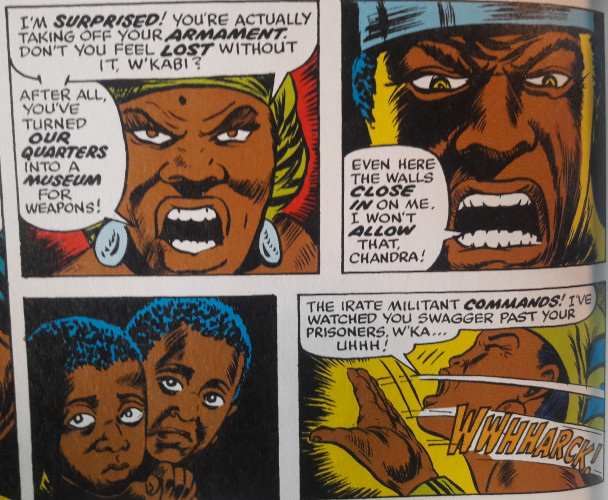

Elsewhere, McGregor’s characters are also unique and engaging. Love interest Monica Lynne receives much screen time; she’s never really given her own story, but McGregor uses her as a “mouthpiece” of sorts, an analogue for the reader to relate to as she navigates this new world of wonder. Perhaps Monica may have been better used as a bridge between the western world and Wakanda--I wonder, if Monica had highlighted some of the disparity between T’Challa’s technology and the state of some of his people, would the tales be slightly better received now? Monica is certainly relatable, but she does sort of drift between chapters. Other Wakandan characters, such a W’Kabi and Taku, are given their own arcs; though these are not quite as deep or engaging, they add complexity to the story and help balance out some of McGregor’s frenetic action sequences.

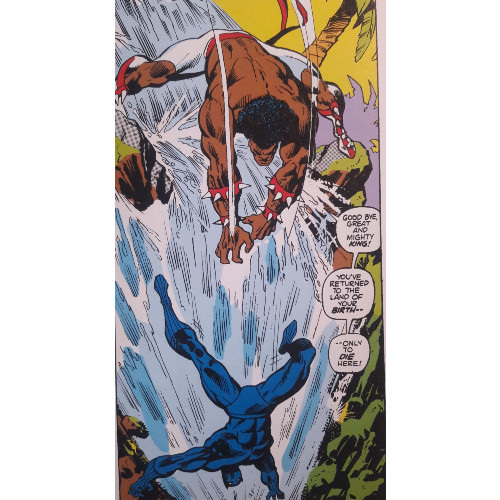

T’Challa, certainly, receives the panther’s share of characterization, and McGregor doubles down on the heroic aspects of the king. One of my complaints about Priest’s run was how “Batman-like” T’Challa became: he had plans within plans and always seemed to bring along the right tool to equip at the right moment. Contrary to Priest’s depiction, McGregor makes T’Challa vulnerable. The guy is put through the ringer--defeated by Killmonger and tossed off a waterfall (which film fans will certainly recognize as the inspiration for the movie’s climactic tussle between the two opponents); ravaged by white wolves; tethered to a cactus-like tree; tossed around by a white ape. T’Challa fights foes after foe, human and animal alike, always rising above his physical limitations to secure victory. He relies on his cunning and physicality, a “never say die” attitude that pushes him past the limits of his strength. He’s heroic, undaunted, and always capable. “Driven” is a good word to describe this Marvel monarch, guided by a willingness to risk life and limb for his people.

McGregor’s story takes a sudden shift at the end of “Panther’s Rage,” as T’Challa journeys with Monica to the American south to investigate the murder of her sister. Smaller in scope, this tale is also unfinished by time the Epic Collection ends (though it’s wrapped up in the second volume). McGregor wrestles with themes of racism and violence as he brings the Panther face-to-face with the Ku Klux Klan and another group of anti-African American terrorists. The issue of racism, as far as I can tell, is handled deftly--McGregor seems to certainly be making a point through this tale, though it’s not presented as heavy-handed nor does it provide an all-encompassing “whites are evil” message. There’s balance to be found in these issues. The evils of racism are solidly addressed while the reasons behind such evils are appropriately confronted as well.

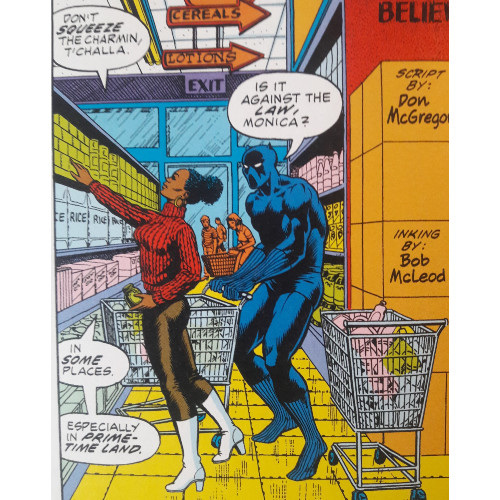

Additionally, McGregor seems to really enjoy the “fish out of water” aspects of T’Challa journeying to America. The Panther is not presented as foolish or ignorant of American customs; in fact, he seems to like the country quite a bit. It’s entertaining, therefore, to have a scene where T’Challa travels with Monica to the grocery store, dressed in full Black Panther regalia. Readers may find it humorous, and while it’s certainly fun, McGregor uses the scene to make a point--why should T’Challa feel ashamed to wear his royal garb, even in a land that is not his home? McGregor doesn’t necessarily make a huge argument in regards of one culture adapting to another, but for T’Challa specifically, it’s a good point. T’Challa is not afraid to adapt to American culture when necessary, but he also believes in keeping his unique personality and customs. Why should that not be acceptable?

A tad more depth can certainly be found in these later issues, and it’s definitely a shame that Jungle Action was canceled prior to McGregor finishing his KKK story arc. McGregor makes some engaging social commentary without being harsh, somehow managing to be relatable to today’s issues without handling the subject matter like writers today might. His efforts to humanize T’Challa as he navigates our society are entertaining, not necessarily for comedic effect, but to give a look at how an individual from another nation might interact with our American culture.

To call this Epic Collection a “mixed bag” would do it a disservice. Though the Lee and Kirby issues feel dated in some respects, the same cannot be said for McGregor’s stint. His tales are compelling, his drama and action guiding you through each chapter and developing plot point. With “Panther’s Rage,” combined with stunning art and gripping layouts by Rich Buckler (of The Death of Jean DeWolff fame) and Billy Graham (not the American evangelist), McGregor shapes T’Challa’s earliest solo adventure very nicely. Future stories, such as Priest’s run and the Black Panther film, owe a debt of gratitude to McGregor and Co. Without their work, where might the king of Wakanda prowl today?