Distinguished Critique: Superman: Birthright Review

Mark Waid's series proves to be an effective, if not the greatest, retelling of the iconic hero's oft-repeated origin

—by Nathan on August 19, 2023—

On his blog, writer Mark Waid has detailed his reaction to watching Man of Steel for the first time (which I've sourced from a site quoting the story as I cannot seem to access Waid's original post). He describes that, at the moment Superman chooses to kill Zod, a “crazy guy” stood up in the theater, shouted at the screen, and nearly left until his more mindful girlfriend calmed him down.

Waid then admits the “crazy guy” was him.

Waid has written at least two iconic depictions of Superman–Kingdom Come, a 1996 limited series illustrated by Alex Ross, and Superman: Birthright, the early 2000s retelling of Kal-El’s origin. The former tells of a possible future Superman who, after being persuaded to put on the cape he previously hung up, asserts a dominant authority over a new generation of young, reckless superhumans. The latter details Superman’s formative first foray into flying feats of fancy, a retelling of the Man of Steel’s early days 17 years after John Byrne’s update. A “last” Superman story vs. a first.

Last year, I examined Birthright through a more academic lens, deconstructing its narrative components for a graduate course assignment. Think of it as an extended summary. This is a deeper dive into what I consider one of my favorite Superman stories of all time. How does Waid’s take differ from Byrne’s? What does he add to the Superman mythos in this new iteration of a timeless tale? And what is it about Birthright which makes it stand out from the many, many other depictions of Superman's origin?

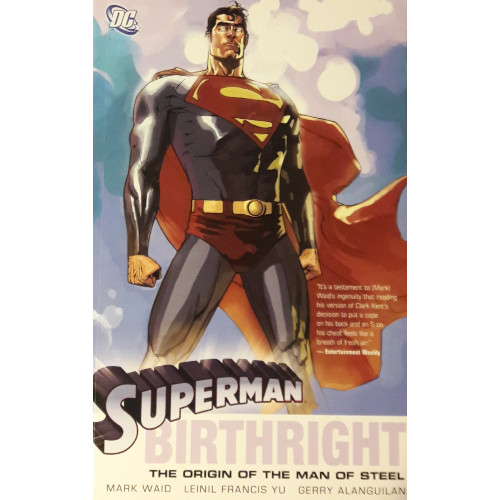

Superman: Birthright

Writer: Mark Waid

Penciler: Leinil Francis Yu

Inker: Gerry Alanguilan

Colorist: Dave McCaig

Letterer: Comicraft

Issues: Superman: Birthright #1-12

Publication Dates: September 2003-September 2004

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

As I mentioned in my review on Byrne's post-Crisis on Infinite Earths take on Superman's origin, the ending to Man of Steel irks me. Byrne's Superman blatantly discards his Kryptonian heritage for his Earthly, American upbringing. And as I commented in my “For the Man Who Has Everything” review, Superman works better when writers view him at the intersection of “Last Son of Krypton” and “First Son of the Kents.” The alien and American heritages intertwined.

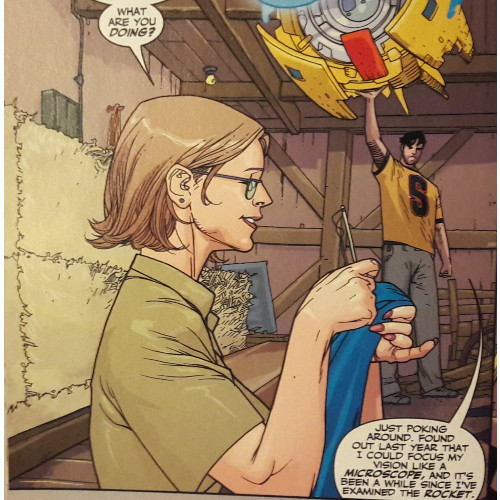

Mark Waid understands this dichotomy perfectly, allowing the connection between Clark’s former and current homes to influence who he is as a person and hero. From almost the start of the series, after a brief retelling of Clark’s rocket-propelled infancy, Waid juggles said dichotomy beautifully. Clark voraciously devours whatever knowledge he possesses regarding Krypton, adapting its culture to his life however he can while remaining true to the principles his human parents instilled in him. This is, as the title implies, Clark’s “birthright.” He’s an ambassador of a dead people, striving to fit in with this living world as a human bridge between two extraordinary, different races.

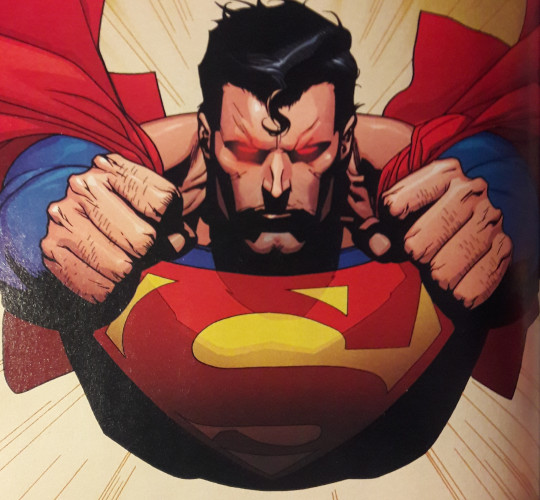

Superman’s “S” symbol permeates Kyrptonian society, and though it stands for “hope,” Waid unpacks that notion better than Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel does. Snyder simply relegates the “S” symbol to a few lines of dialogue. To Waid, the symbol is inherent in Superman’s understanding of himself and his world. It signifies Clark’s entire race, his whole culture, a constant theme/image weaving its way through Kryptonian history. The symbol itself stands for hope, making Clark realize the legacy he’s supposed to carry as not only a human hero but as a representative of his people. When villains later co-opt the symbol for their own nefarious purposes, Superman has to literally take it back. His symbol, and the memory of Krypton, is not meant to be abused in such a fashion.

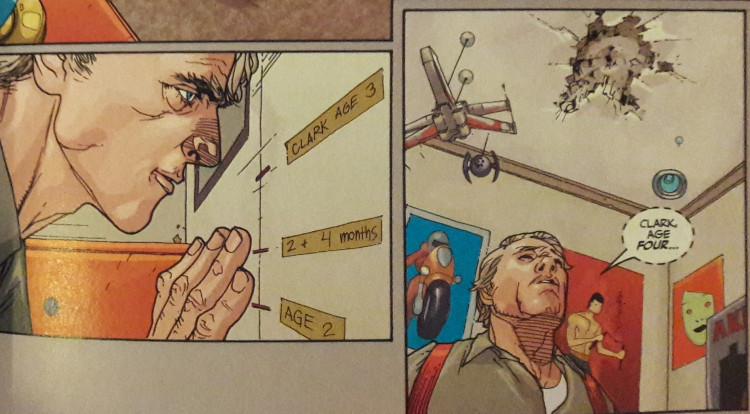

Simultaneously, Waid explores the human side of Clark. Early scenes between Clark and his parents showcase just how integral they are to his life. Clark’s heritage may be connected to Krypton, but his formative years are tethered to Earth and Smallville. Waid includes beautiful imagery such as a dent in the Kent’s ceiling Clark made as a child or Clark with bundles of seed he helps his father move. Waid wonderfully showcases the unique struggles and advantages that come with raising a child like Clark; a few later scenes see Jonathan Kent struggle to understand his son as he comes to grips with the young man’s decision to go, as Jonathan sees it, “play superhero” in the big city. He’s forced to grapple with Clark’s plans, with Martha encouraging those plans, with the idea that the son he’s known and loved all his life is not just your average kid. As Clark strives to understand the two halves of himself, so must the Kents force themselves beyond initial frustrations to understand that same dichotomy.

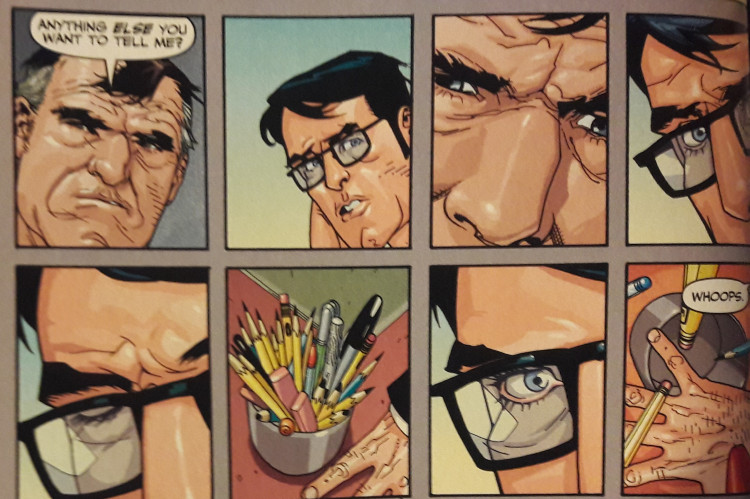

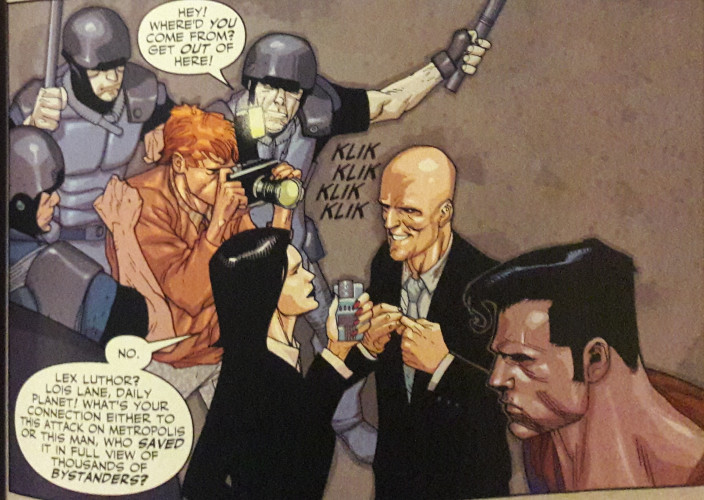

Naturally, any analysis of Clark’s “human” side also includes his interactions with Metropolis, The Daily Globe, and its pool of staffers including Jimmy Olsen, Perry White, and long-running love interest Lois Lane. Waid crafts these first interactions as well as he creates scenes with the Kents; the often-aloof, klutzy Clark Kent uses his awkwardness to great effect as he bumbles along with his superior and coworkers. A couple different scenes picture Clark apart from other Globe employees, either listening in on a conversation about him from a few pedantic coworkers or being completely overlooked by janitorial staff shutting down the office for the night. In other words, he does his job too well…yet to hilarious effect. Periodically, Waid stresses the point a bit too much–Clark’s first interaction with Perry White sees the new reporter intentionally knock over a pen holder (literally, one might say, leaning into his disguise); as much as this helps establish Clark’s “klutzy” nature, the art and dialogue fail to make the moment seem purely accidental.

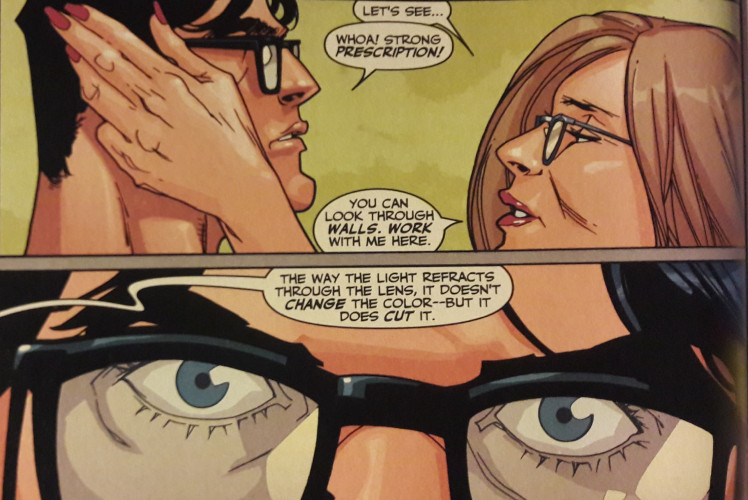

Waid is better able to rationally justify several of Clark’s choices behind his bumbling reporter persona. The fit young man hides his size under bulky jackets; he alters his voice when talking as Superman; he wears a pair of glasses to minimize the bright blueness of his eyes. Waid goes through these alterations piece by piece, crafting a unique visual persona for Clark to assume. One can easily slap a pair of glasses over his eyes and run with the simple notion that no one would be able to tell the difference between Clark Kent and Superman; Waid, to his credit, attempts to establish particular reasons behind these decisions, working them into the narrative rather than letting the notions stand silently on their own.

Lex Luthor, Superman’s arch nemesis, is given almost as much page space as Clark. Where other writers had developed him as a madman or a corporate businessman from the get-go, Waid dips into the character’s past to better understand how he became the ego-centric mogul who holds Metropolis in the palm of his hand. Waid tethers Lex’s past to Smallville, a previously introduced bit of continuity Byrne seemingly retconned with his series. Some of Waid’s more powerful scenes see Clark and Lex develop a friendship as Clark tries pulling Lex out of his self-created shell.

Waid establishes Lex’s mannerisms and personality as, not just the result of his genius, but as something deeper, a personality issue perhaps. Lex behaves far differently than his peers, and even the adults around him, and for all his intelligence seems genuinely incapable of crafting natural human relationships…outside Clark. Waid forges this connection of “otherness” between them–Clark, the actual alien, befriending Lex, who feels like an alien or at least as out of place as a person can feel in their hometown. Both boys are different in their own way and all Clark wants to accomplish is help Lex better understand his uniqueness. But Lex struggles to listen and understand from Clark’s perspective, even as he wishes people understood him better. These conflicting mannerisms extend into adulthood, as Waid crafts an antagonist who isn’t necessarily evil for the sake of villainy or greed…but as someone who just wants to be seen. Like Clark, Lex has his own “birthright” to grapple with.

What Waid does best is give his characters a lens to focus their growth through. In this case, the key word really is “birthright.” The word focuses on the purposes, powers, and possibilities Waid’s characters are born with, and the struggle throughout the series becomes how those characters respond to those details. You see it in how Clark wrestles to reconcile his Kryptonian powers and purposes with the Kents’ virtues. You see it when Jonathan Kent struggles to view his son, the boy he raised from an infant to a man, embracing a superhuman side of himself Jonathan doesn’t fully understand. You see it in how Lex fails to fashion meaningful relationships with most folks and squanders the one he does form, sinking deeper and deeper into himself as a result.

As he crafts fantastic characterization, Waid never forgets this is a superhero comic, even if it is a pithy, introspective superhero comic. A good chunk of the series’ third act is dedicated to Superman’s battle against a fake Krptonian army as Luthor attempts to ruin the goodwill Clark has created in Metropolis. No other “supervillains” appear throughout the series, but Clark is given the chance to stretch his sun-soaked muscles against gunmen, terrorists, and naturally occurring disasters. There’s a grounded, vaguely post-9/11 aura permeating the series. Sure, chunks of green space rock and robots appear, but most of Waid’s series feels engagingly and refreshingly down to Earth.

Birthright is perhaps not quite as joyful as Byrne’s renditions–moments in Man of Steel certainly feel more “fun” than modern depictions of the character–but Waid's origin story never comes across as excessively grim. More serious undertones run through the story, but at its heart, Waid’s story is entertaining for all the right reasons: strong writing, a great cast, powerful themes, and a Superman you’d never confuse with a bird or a plane.

A scene near the end tethers beautifully to the beginning, serving as one of the most emotionally cathartic moments I’ve read in a comic. It brings Waid’s story full circle, reminding viewers of where Superman came from and how his origins shaped his present. As you skim the final panels, you realize how deep Superman’s identity is tethered to home–whether it’s the planet he doesn’t remember, the small town where he was raised, or the metropolitan city where he established his superhuman persona–and how important his birthright truly is to the man and hero he’s become.

This story–Superman's origin and formative years–has been told and retold...a lot. It's not just Byrne and Waid. I intend on reviewing other takes on the character's early days by Mark Millar, Geoff Johns, Jeph Loeb, and Max Landis. Heck, even Kurt Busiek's Secret Identity series is an origin story for a version of Superman, and I hope to review that too. And that's not counting the sheer number of parodies which have included some twisted facet of Clark's classic coming-of-age tale. Of all of these, Birthright has become for me the definitive version of Superman's origin, retcons and shifting timelines and big event stories be darned. Gorgeously written, cathartic, and never losing its human element, Birthright makes an incredibly strong argument for why Superman has been around as long as he has...and if we can get more comics and movies written as well as this series, he may never leave us for whatever is up, up, and away.