Distinguished Critique: Crisis on Infinite Earths Review

This classic, catastrophic condensing of the DC Universe excites and amazes, but its bombast and agenda cultivate more set-pieces than engaging character moments

—by Nathan on April 25, 2023—

The multiverse.

A spiraling cacophony of worlds, a puzzle of diverging pieces laid atop one another, an environment where the you on one Earth may be a completely different person than the one in another. Comics have adhered to the concept for decades, crafting several universes where different events transpire in an alternate fashion than in some company’s mainstream world. What if the Flash wasn’t Jay Gerrick but Barry Allen? What if Spider-Man was killed by Kraven the Hunter instead of drugged and buried? What if Superman had never been found by the Kents?

In the 80s, DC decided to cut back on their multiversal diet in a quite literal fashion. Marv Wolfman and George Perez brought their talents to the twelve-issue limited series Crisis on Infinite Earths, intending to slim down the DC Universe, scaling back and creating a much more organized place for the likes of Superman, Batman, and other heroes to roam. The series is considered a classic, a highwater mark in not only the careers of both men but a watershed moment in DC history. It seems like as good a place as any to begin our romp through the DC Universe. As I started in the 80s with Marvel, so I begin with DC in relatively the same era. Nearly forty years later, how well does the series hold up as a narrative?

Crisis on Infinite Earths

Writer: Marv Wolfman

Penciler: George Perez

Inkers: Dick Giordano, Jerry Ordway, Mike DeCarlo

Colorists: Anthony Tollin, Tom Ziuko, Carl Gafford

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: Crisis on Infinite Earths #1-12

Issues Publication Dates: April 1985-March 1986

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

I’ll admit, right off the bat(man), I’m not a huge consumer of DC comic books. I have a small-yet-growing collection which pales in comparison to my Marvel trove. I’ve certainly read various stories and seen movies over several years, but in comparison to my understanding of the Marvel Universe, my knowledge of DC canon is much lighter. As a result, I am not necessarily tackling Crisis from the point of view of a fan who deeply understands the intentions behind the crossover epic or the historical ramifications of the series. I am examining this as a much more casual reader, mainly interested in the broad narrative appeal rather than the more specific intricacies as they relate to the DCU at large.

I do know this, however: Wolfman and Perez’s saga was intended to pare down the number of universes contained within the DC multiverse; credit must be given them for approaching this from a narrative perspective. It would have been so easy to dedicate a single issue or a handful of panels to a cataclysmic event which saw worlds wiped out by the dozen. Wolfman and Perez took what could have just been an editorial edict and integrated it into the universe itself, a wonderful re-framing of the situation. It’s highly entertaining when you view the series from this lens. All of a sudden, the enormous Anti-Monitor isn’t just another galaxy-threatening villain: he’s the intentions, desires, and demands of the DC higher-ups...and, if they get their way, he succeeds. Sort of. Yet he’s framed as this colossal bad guy, a godlike threat to be ended by our collective cast.

Wolfman and Perez, in a sense, toy with the reader. Perhaps this comes from the benefit of hindsight. I don’t know if Crisis was initially marketed as “the end of the multiverse as you know it.” I’m not certain if readers, heading into these issues for the first time, were aware of the series’ end goal. But coming into the series over thirty years after its initial publication, you see the amusing dichotomy at play: a villain who must be stopped, just like any other villain, but his machinations, largely, have the support of his creators or his creators’ bosses. What are our heroes to do?

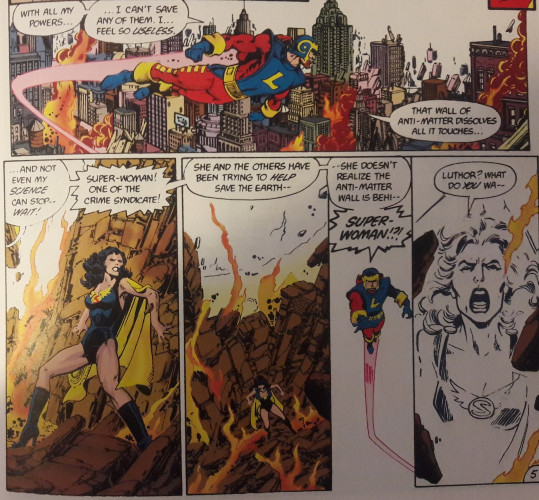

The narrative itself, while not entirely gimmicky, does feel encumbered by this “eliminate the multiverse” injunction, though not at first. Certainly, Wolfman does his best to encapsulate the idea within an entire story, to keep the massive fluctuation from feeling gimmicky or like a random idea thrown in because it needed to happen. He and Perez set the stage beautifully, teasing the Anti-Monitor’s plot without providing too much detail. The series opens with universes engulfed. The Crime Syndicate of Earth-2 struggle to keep a wave of anti-matter energy from consuming their world. Heroes and villains alike perish from these devastating incursions. The stakes cannot be more massive.

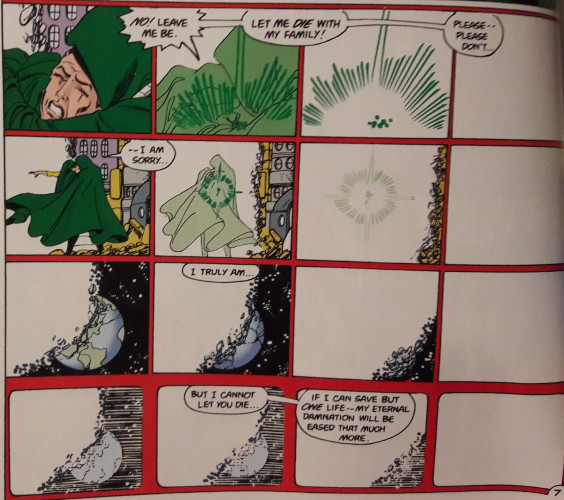

Perez’s artwork, particularly his ability to play with panels and utilize the space between panels, gorgeously captures the pandemonium in all its detail. His backgrounds and character work are fantastically rendered, showcasing the raw emotions displayed by our heroes. You see the fear written on the faces of men and women who, normally, would be able to stand up to threats like this wave of devastating energy. They’re shaken, desperate. They’ve fought so many villains, halted so many threats, yet even they are powerless against a pure wave of anti-matter.

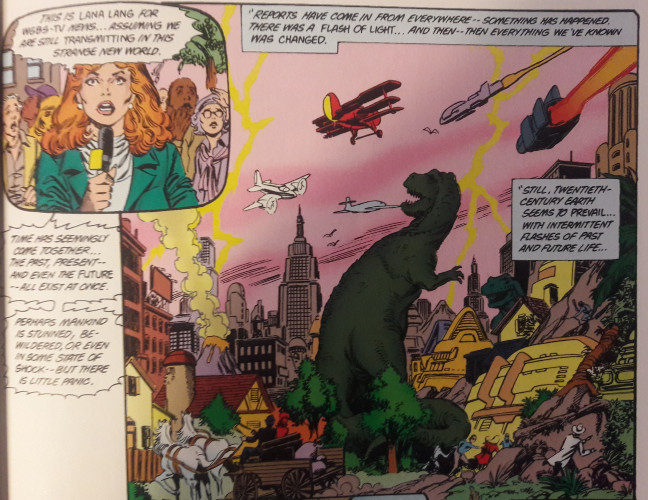

Wolfman’s story isn’t a mystery, but it’s a slow burn that constantly builds upon itself. And this “building” is where the narrative often becomes stuck. The story is so huge, so massive, that Wolfman feels the need to constantly one-up himself but never adequately seeds recurring conflict to justify the length of twelve issues. The Anti-Monitor always, always seems one step ahead of our heroes, his machinations hinging on a level of fervent ridiculousness that, today, would seem parodical. Giant towers rise from the ground on several earths, forcing our heroes to confront shadow monsters in pitched battles which usually feel indistinguishable from one another. Worlds literally collide, causing havoc as entire timelines blend and merge. Heroes confront the Anti-Monitor directly several times, once at the very beginning of time itself. I'm all for wacky pandemonium on a cosmic scale, but your stakes should feel realistic even when the action doesn't. Jim Starlin's Infinity Gauntlet works precisely because of the human element–at the heart of a story about the temporary demise of half a universe lies a villain with a crush on Death and heroes waging war on the side of life. That element seems vague in most of Wolfman's narrative; it exists, but it meanders in-between the bombastic action sequences.

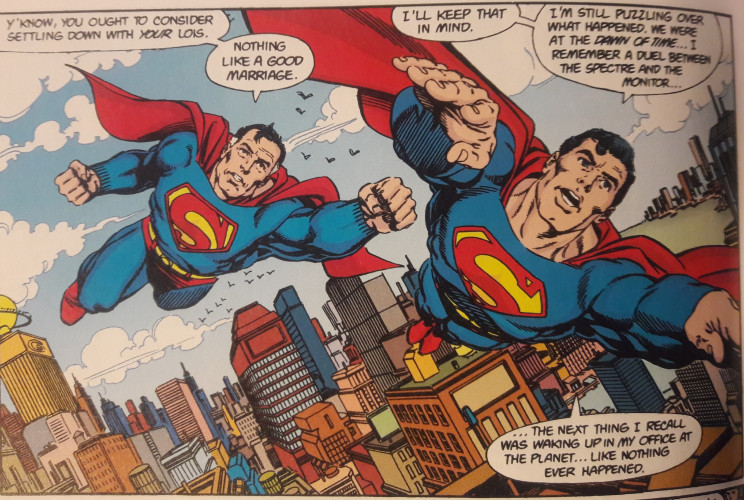

I suppose, then, I wished for more consistently engaging characterization. Wolfman's narrative often succeeds best when he weaves smaller conflicts into the universal-scale happenings. The “colliding worlds” piece brings several unique aspects to the series and some engaging conflict as people from different worlds and timelines struggle to figure out just what is going on. Their confusion is palpable and creates engaging strife that Wolfman writes wonderfully when he’s not scripting cosmic battles. But at some point, his attempt to constantly eclipse himself becomes goofy and stale; his desire to overshadow what happened before is itself overshadowed by sheer ridiculousness. When the Anti-Monitor enacts his third or fourth “plan within a plan,” the repetition is obvious. Wolfman even uses the final issue’s doubled size to enact some last-minute, extra action sequences, pages which could (and, in my opinion, should) have been used for more character driven moments.

Perhaps it’s the scope of Wolfman’s conclusions which makes the final issue in particular feel egregiously underwhelming. Once the dust has settled, the DC Universe is irrevocably changed. Yet those changes are largely left for various other series to explore and navigate, however that occurred. Granted, you could argue that’s the point–similar to how Marvel’s Super Hero Secret Wars crossover allowed their heroes’ respective titles to deal with the crossover’s fallout, so were relaunched titles with Superman, Wonder Woman, Flash, etc. intended to deal with the ramifications and simplicity of a unified DC universe. It wasn’t necessarily Wolfman’s prerogative to explore the ramifications of the simplified world. But powerful moments are left to single panels depicting funerals, mourners, characters reeling from the chaos which has ensued. The moments are interesting to reflect on but leave too little an impression to last beyond these frozen seconds.

During the series, Wolfman does attempt to course correct this with flashes (no pun intended) of characterization. As I stated, his opening kicks off the story entertainingly–heroes work with their greatest foes to keep the anti-matter from spreading, and Lex Luthor of Earth-2 kisses his wife farewell one last time after firing their infant son off into the unknown (sound familiar?). A scene between Supergirl and Batgirl works to effectively contrast the two characters without resorting to their male, adult counterparts (making me wonder how often the two have been paired as Superman/Batman team-up analogues). Supergirl’s later demise is constructed fantastically, heightened by a last-ditch effort against the Anti-Monitor and her cousin’s pained reaction to her death.

Characters react well to the circumstances around them, especially as individuals from the past and future interact with each other after being thrown together. And several heroes, aware of Wolfman’s brand new earth, briefly explore the newly minted landscape with awe and fear. An older Superman realizes his version of Krypton no longer exists, and Jay Gerrick and Wally West work through a reality without Barry Allen. Again, several ramifications are left unsaid, such as Wally picking up Barry’s mantle and becoming the new Flash. Still, promises are given to fans wishing to read series that were jumpstarted after Crisis.

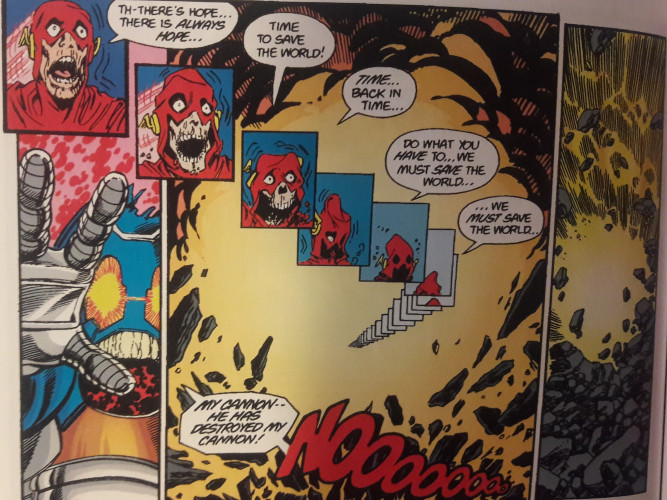

What we’re left with is a series divided–Crisis is, by and large, successful in carrying out its massive premise. Yet Wolfman’s hampered ability to navigate such an enormous plan makes for a somewhat jumbled, repetitive, stilted story. He maneuvers characters at Flash-like speeds, leaving a whole host of DC heroes and villains feeling little more than blips on his cosmically attuned radar. The impact is certainly far-reaching, yet the interesting, character-related ramifications feel lost in the shuffle. Moments shine here and there–I, at last, fully understand the enormity of Barry Allen’s sacrifice–but to pluck out a handful of moments from this twelve-issue saga feels a little defeating. Perhaps it’s impossible to expect a thoroughly engaging story given its absolutely insane premise or expect Wolfman and Perez to keep you interested in every single character to dot the page. They do attempt to hone in on certain characters–Supergirl’s death wouldn’t be quite as impactful, admittedly, if it weren’t for her earlier discussion with Batgirl. But Crisis, in working to narrow the scope of the DC Universe, strangely feels too big at times to properly hook the reader. Oddly, it’s through the smaller sequences that the series really leaves a big impression, making so much of its universally massive premise feel like fluff floating through a radically changed, somewhat blank-ish slate of a DC Universe circa 1986.