Spider-view: “Hero Worship” (Alien Costume Saga, Part 16)

This Marvel Team-Up issue tells a winning story about herosim without coming across as heavy-handed or preachy

—by Nathan on November 27, 2020—

Heroes.

We admire them, right? Men and women, real or fictional, that we’re drawn to because of their strong, moral characters, their courageous deeds, their staunch resolution in the face of adversity...we honor them and emulate them. For some, their “hero” is the firefighter or police officer who saved their lives; for others, it’s the parents who sacrificed so much in raising them from childhood to adulthood. Many faces, many names, but united in purpose and direction.

Marvel Team-Up, like many comics from the proud creators of Captain America, the X-Men, and others, featured dozens of heroes, many fans know by heart, others they may have been introduced to for the very first time. What may surprise you is that some of those superpowered people have heroes of their own, men and women they look up for inspiration in the line of duty.

This is one of those stories, one that touches on a hero’s hero.

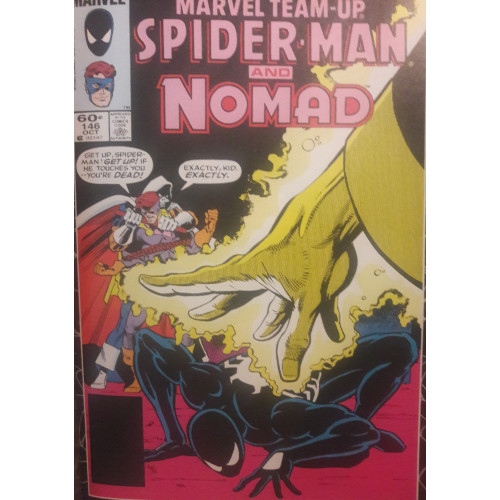

“Hero Worship”

Writer: Cary Burkett

Penciler: Greg LaRocque

Issue: Marvel Team-Up #146

Publication Date: October 1984

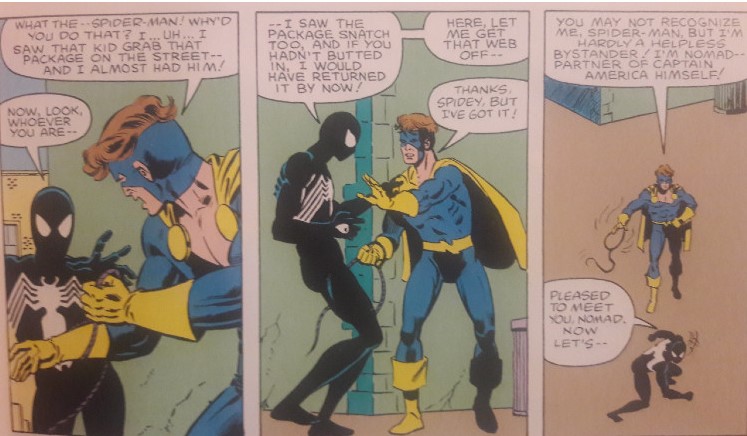

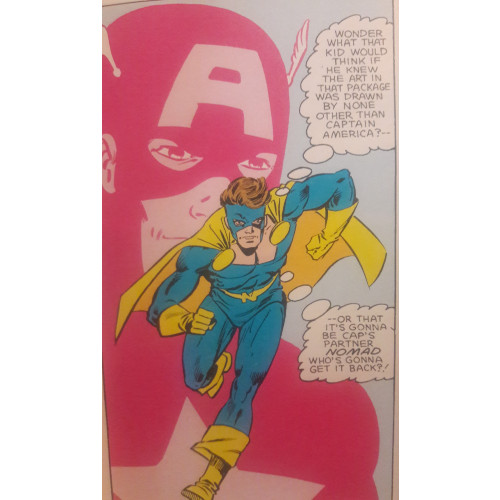

The masked man Spidey works with in this issue is Jack Monroe, going by the name of Nomad. He’s a character, much like other heroes Spidey fights alongside in these issues, I have not had much exposure to in my comic book reading. I do know that he was the sidekick of a Captain America in the 50s while Steve Rogers slumbered in ice and, years after this story debuted, he was murdered by the Winter Solider, aka “Bucky Barnes,” Steve’s original sidekick. But that has little to do with this story.

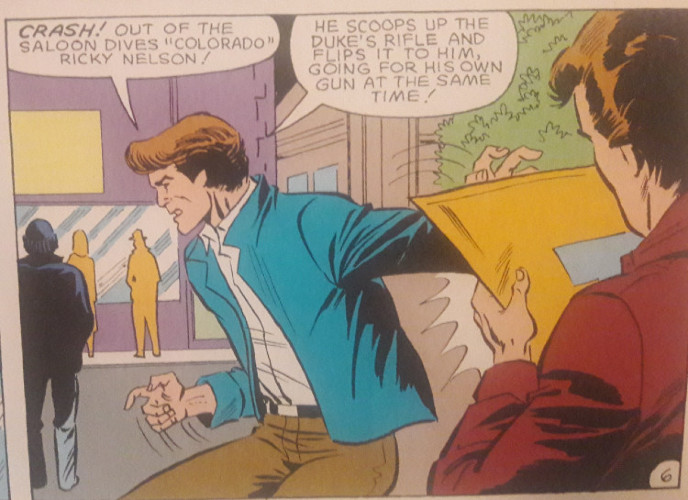

Perhaps the only factors from Jack’s history that are relevant to this tale are (1. He was put into suspended animation back in the 50s and (2. He knows Steve Rogers. The first factor largely leads to some awkward dialogue between him and a plainclothes Peter Parker, whom Jack meets prior to bumping into Spidey. Peter is confused when Jack speaks of an old John Wayne Western like he saw it back when the film premiered, which is true! The scene, played for laughs, actually plays well into Burkett’s theme of admiration of other people’s heroes. John Wayne is, clearly, an inspiration to Jack, given how enthusiastically Jack speaks of the film.

Jack’s admiration for one other hero, the Star-Spangled Man With a Plan, is less verbally regarded and more nodded to and then depicted in Jack’s actions. At one moment, Jack gets a hold of a foe’s shield and flings it like he’d done while training to duplicate Captain America’s own prowess with a metal Frisbee. His quick thinking in rescuing a young boy from a burning building, not to mention his own willingness to enter the conflagration, all seem to stem from whatever courage was planted in him by Cap’s example.

Oddly enough, the same cannot be said for Peter Parker. In a story that hinges on this notion of “hero worship,” I was surprised and a little disappointed that Peter, either as himself or as Spidey, never mentioned any of the heroes he “worships”--one could argue that the “death of Uncle Ben” angle has been used so many times by this point it’s more of a cliche than a lesson to reflect upon, but it’s still a bummer not to hear Peter’s reflections on the notion. No hints exist, no nods point to any of the individuals that have inspired Peter to be the hero he is today, and considering that Nomad views Steve Rogers in such high regard, I would have loved to hear how that applies to Spidey as well, to balance things out.

On the flip side, Burkett’s lack of Spidey references means the story never gets bogged down by expositional fluff. No one goes on for pages and pages about the positive qualities of heroism, no one gets a pep talk about what it means to be a hero or how you can live your life inspiring others. Messages such as these are fine and dandy, but comics tend to fumble the ball most times when they try to insert a moral in their tales. The dialogue is heavy-handed and obvious, reliant on description and repetition over subtle metaphors.

Instead, Burkett gives us a young boy named Tony and uses this character to get his message across. Tony, for some strange reason, looks up to a local gang of street toughs and their “fearless” leader, begging for an opportunity to join their ranks and prove he’s got the stuff to be one of the Butcher Dogs (ooh, menacing!). As the issue goes on, and as the Butcher Dogs continually reject his interest, he begins viewing them through a different lens and, once he’s rescued by Nomad, decides to set aside his dreams altogether for a new purpose. We don’t get much of Tony’s background--like where he’s from, where the heck his parents are or if he even has any, or what his relation to the members in the Butcher Dogs is--but Burkett still crafts a character you can empathize with; the boy becomes a mouthpiece of sorts for Burkett, but not in an overly obvious, irritating way. Burkett isn’t trying to hit you over the head with “Pay attention to this kid! He’s the crux upon which my thematic message hinges!” Enthusiasts of narrative are certainly familiar with the method of using one central character to become a microcosm for the plot’s entire message, and in some cases, it becomes blatant to the point of painful. Tony isn’t some kind of fabled “Chosen One” who you’re constantly reminded will determine the fate of the universe; he’s just a kid who’s been dealt a bad hand who, by story’s end, sees a glimmer of hope after his interaction with Nomad and Spidey.

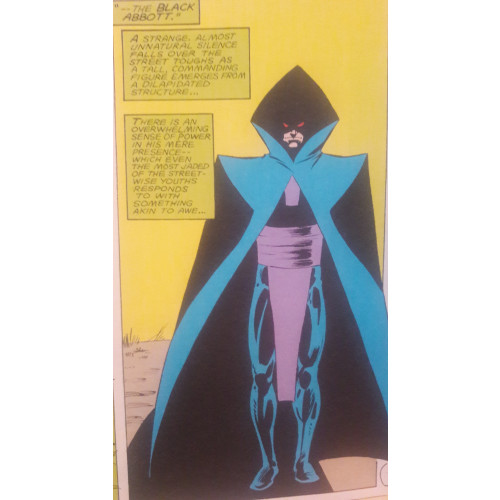

But when you have a clear intention to define how things should be, like a young boy’s life that should be filled with hope with promise, you often need to juxtapose it against how things should not be. Hence the supervillains. Burkett brings back a classic villain, Taskmaster, whom Spidey had faced in MTU #103 (which I, unfortunately, do not have access to currently), and also introduces an original creation: the Black Abbott. Abbott’s own story will be revealed in a few issues, but for now, the mysterious man with mental manipulation abilities remains a shadowy threat. LaRocque’s design for the character is brilliant, shrouding the villain in dark robes, and Burkett crafts enough secrecy around him to make him ominously riveting. Given religious undertones, Abbott nicely steers clear of stereotypical Bible-thumping baddies who quote verses out of context with an overly dramatic flair. Abbott’s tone and mannerism still indicate some form of religious background, and Burkett makes it clear that the villain is utilizing his background in a twisted way, but he comes across less as a preacher gone mad and more like a misguided fanatic.

Burkett’s theme of heroism gets warped by Taskmaster and Abbott as well when Taskmaster tries to recruit several of the Butcher Dogs for Black Abbott’s organization. Here, serving a greater cause is seen less as an act of sacrifice and more for the allure of profit. Black Abbott doesn’t even discuss his plans for the Butcher Dogs, making no comments about world domination or upending the established order. It all seems to be part of the mystery Burkett’s weaving through the issue about his new villain, which I will say is established decently. Burkett showcases the supervillain’s abilities against his foes but keeps him on the fringes, clearly working to set Abbott up for a future display of strength.

This is, I believe, only the second MTU issue we’ve encountered that is only a chapter within a larger narrative. Until now, other than the David Michelinie-penned two-parter starring Captain Marvel and Starfox, other Team-Up arcs have been standalone stories. I enjoy seeing Burkett and LaRocque establish elements that they intend on carrying over into other issues; this issue feels a little weightier, knowing that pieces will transition over into additional chapters. Seen as a single issue, MTU #146 does feel a little unfinished, but that’s only because it wasn’t intended to be a one-and-done. Impressively, Burkett doesn’t really lead you to believe this is the first chapter of a bigger story--no cliffhangers, no references to larger plans at work, etc. In hindsight, though, I prefer it that way. He leaves Abbott hanging out in the background, letting the reader wonder if the character will ever return. Since he comes back in the very next MTU tale, your patience is rewarded...and you didn't even know you were waiting!

My complaint about Spidey still stands, and since he doesn’t necessarily partake in the thematic elements Burkett unspools regarding heroism and the impact people can have on the lives of others, his appearance feels more based on his regular appearances in MTU rather than his own contributions. Elsewhere, Burkett manages to craft a decent story about heroes inspired by other heroes and even how that idea is compounded--the tale ends with Tony inspired, not by the Butcher Dogs, but by Nomad after Jack rescues him. The idea is a nice one, a positive note to leave the issue on and one, as I said, that doesn’t feel overly preachy (“Remember, kids, it’s good to be nice to people!”). For a medium that often struggles to lay out moral messages plainly but with good taste, I’m glad to see that Burkett and LaRocque succeed where others have failed.