Spider-view: “Masques”

McFarlane's second Spider-Man arc fares as well as his first--wonderful visuals straining to carry a thematically lackluster story

—by Nathan on March 10, 2022—

Welcome, dear friends, to Part 2 of “Todd McFarlane’s solo romp around the Spider-verse.”

When last I discussed McFarlane’s Spider-Man title, I analyzed “Torment,” his first foray into a world he both illustrated and wrote. I praised his detailed art, the way he rendered the monstrous Lizard and Spidey’s webbing, but I criticized his ability to carry his story. The narrative itself was amusing and interesting, but McFarlane attempted a deeper, introspective gaze into our characters and ultimately came back up gasping for air with little to show for his deep dive.

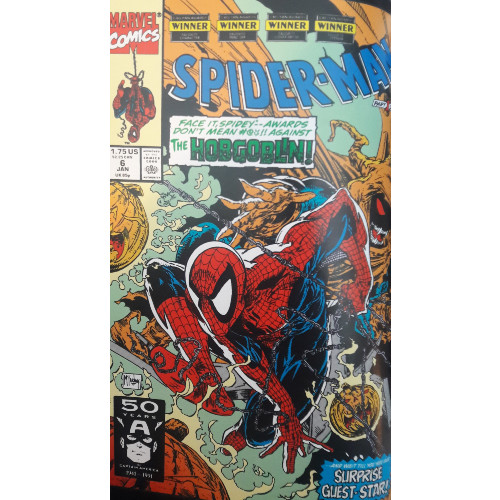

We’ll see that he tries something similar in this two-part follow-up, as McFarlane gets himself a little entangled in the long-running mystery/headache that is the saga of the Hobgoblin.

“Masques”

Writer: Todd McFarlane

Penciler: Todd McFarlane

Issues: Spider-Man #6-7

Publication Dates: January 1991-February 1991

The Hobgoblin (currently Jason Macendale) re-emerged recently, as part of Doctor Octopus’ resurrected Sinister Six, filling the spot left open by original member Kraven the Hunter’s absence. At the time, he was also possessed by a demon after a pact he made during the Uncanny X-Men “Inferno” crossover. Eventually, Macendale will split with the demon, resuming his activities as regular old Hobby while the monster becomes the Demogoblin. I mention that here because it is an arc I currently do not have access to and most likely will not cover. But you should know that, in "Masques," Jason is still bonded with his demonic roommate.

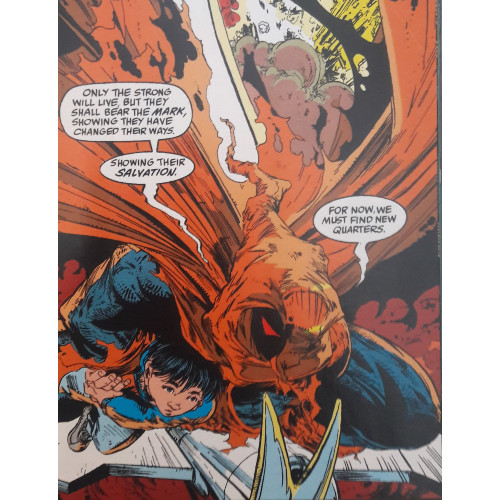

Interestingly, at some point, Jason had seemingly found religion. I am not 100% sure if this was McFarlane’s idea or if the notion had been planted earlier. On the surface, the idea of a guy inhabited by a demon finding religion and spouting generic religious lingo–he tells people to pray, he discusses salvation–is a very interesting take on Hobgoblin’s character. A brief, shallow glance at Hobgoblin notes the interesting juxtaposition between his current, possessed state and the lingo he verbalizes. Is this Jason’s way of combating the demon inside him? Is it the demon disguising itself through Christian-ese? Is McFarlane using the character to comment on religion or church structure or demonology?

The answer to that last question, easily, is no. I don’t think it’s necessary that each writer imbues their characters with super deep understanding or make everything they say or do poignant. But here you’ve got a guy possessed by a demon following a seemingly righteous road–at least, through his own twisted thinking–and McFarlane doesn’t follow the path. He takes the whole notion at face value, throwing in the right words and phrases but not allowing the concept to impact Hobgoblin beyond that.

I would love to know what McFarlane’s thinking was in making this character decision. Other writers had utilized the character, obviously. But Michelinie, in “Return of the Sinister Six,” simply brought in the Hobgoblin as Kraven’s replacement; he briefly comments on Macendale’s new inhumanity but doesn’t stress its importance. Gerry Conway, in a Spectacular Spider-Man story I didn’t cover, also makes a small mention of Macendale’s demonic influence but doesn’t let it impact his characterization. McFarlane actually makes Macendale’s possession part of his character in a potentially interesting way and may be the first writer to have done so. Unfortunately, as I stated in my “Torment” review, McFarlane’s words grasp at the surface layer of dirt beneath the character and don’t dig deeper. If anything, I’m left understanding that Macendale fully believes in his own righteousness–again, an interesting concept, especially through a demon-possessed character, but nothing McFarlane comments heavily on.

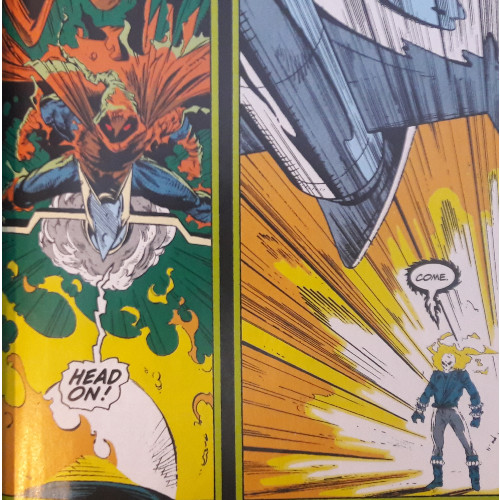

Additionally, McFarlane tries creating this juxtaposition between Ghost Rider (Danny Ketch, the second character to wield the motorcyclist’s mantle) and Hobgoblin. Rider, too, is possessed by a demon and, like Hobgoblin, speaks with a religiously-influenced dialogue. Both men behave as if they’re on the side of the angels, despite their demonic influences. Rider’s tactics tend to be more admirable–where Hobby kidnaps and murders individuals he deems sinners, Rider goes after people who are genuine criminals. Through Rider, McFarlane briefly touches on this notion that a character with such a grim basis could actually act heroically; Hobgoblin, in his own mind, thinks he’s a hero…but his actions prove otherwise.

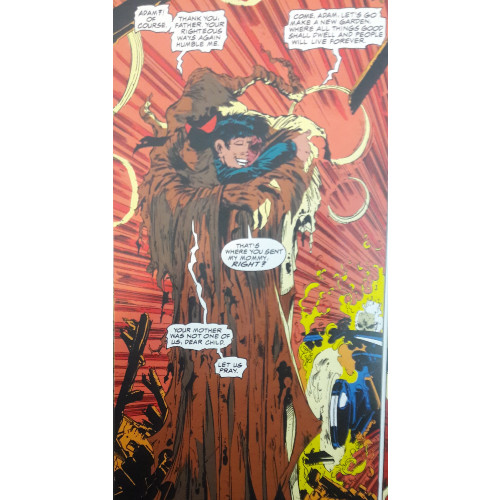

In the midst of this, McFarlane pulls in a young man Hobgoblin drafts to be his “disciple” after the villain murders his mother. The boy feels like he’s supposed to be the centerpiece of this two-issue saga, the character whom all the story beats are intended to revolve around. He’s the kid both Hobgoblin and Spider-Man are trying to save–the latter hopes to keep the boy away from the crazy, flying maniac spouting mumbo-jumbo, and the former hopes to pull the kid from a life of…something evil? McFarlane never actually explains why Hobgoblin murders the boy’s mother, along with several other people he’s kidnapped. They’re supposedly sinners, trapped in their own lies, that Hobby's decided to remove from existence. But are they? McFarlane never defines whether they’re people who’ve done degrading things like kick puppies or if they’re just a random assortment of people Hobby kidnapped. And as interesting as it might be for the Hobgoblin to take a young man under his (glider) wing, nothing much comes from the plot.

Check this as an example: near the end of the story, when Spidey asks the boy for his name, Jason’s young devotee replies, “Adam.” Spidey responds that it’s a very appropriate name. McFarlane’s thinking, I’ll wager, is that Adam was the first man created by God in Genesis; due to the story’s Biblical tones, Spidey must find the connection interesting. But it isn’t. McFarlane could have thrown in a variety of common Biblical names--Peter, David, Nathan (whoo! whoo!), Michael, Daniel, Matthew--and had Spidey respond similarly. There's nothing inherently interesting or poignant about the boy's name. Maybe if McFarlane was telling an alagorical story where Jonah Jameson was swallowed by a whale, he'd have a stronger tether to the original Biblical narrative. Fortunately, McFarlane doesn't beat us over the head with repetitive "first man" imagery, but he doesn't take care to craft an interesting connection either.

I don’t want to get all up in McFarlane’s face for trying to insert religious commentary. As a writer for Geeks Under Grace, I have analyzed several stories which reflect different religions or view religion, Christianity in particular, through a lens different from what I believe. Look at Neil Gaiman’s Eternals or Mark Waid’s Kingdom Come to see different writers’ views on God and religion. Though I disagree with those particular takes, I see their stories as wrestling with notions of God, organized religion, and their views on Christians. Were McFarlane interested in this type of dialogue or commentary, I think I would be more supportive of his efforts.

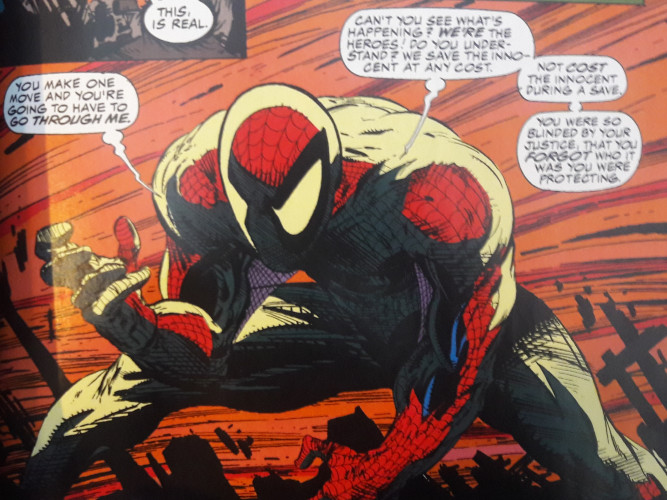

The problem is…he isn’t. He’s not engaging an audience, he’s not wrestling with his own beliefs, he’s not crafting commentary. Again, the ideas he inserts are interesting–particularly the two demon-possessed characters fighting for their own ideas of justice or righteousness–but are never deeply explored. Instead, McFarlane dumps in several familiar phrases and cliched words and calls it a day. He calls a character “Adam,” waiting until near the story’s end to tell us, as if the reveal is dramatic or profound. Like with “Torment,” his dialogue betrays his narrative. “We save the innocent at any cost,” Spidey tells Ghost Rider late in the second issue, “not cost the innocent during a save.” Interesting notion, but McFarlane’s attempt at making his phrases parallel one another is awkward. I acknowledge the attempted rhythm, but the result, here and elsewhere, is lacking.

“Masques,” like “Torment,” does possess (pun not intended) one saving grace (also not intended): its art. McFarlane shines yet again when applying pencil to paper, just so long as his lines, swirls, loops, and dashes are crafting characters instead of comments. Fight scenes between Spidey, Rider, and Hobby are bombastic, filled with eerie flames and high-octane explosions. For all the difficulty McFarlane has in crafting Hobgoblin as a righteous demon narratively, he succeeds in making the villain a grim monster–leering facial expressions, a long, tattered cloak, and a grimacing grin all succeed in giving the Hobgoblin his most demonic look since his pact during “Inferno.” One grand moment sees him turn a gargoyle into a new glider after Ghost Rider smashes the first; it’s incredibly appealing, visually, and a darn amusing idea that makes me wonder why other Goblin-themed villains hadn’t given their gliders a similar appearance.

Yet the visuals, grand as they are, cannot uphold McFarlane’s weak narrative. The entire story is tinged with intrigue: men possessed by monsters trying to do right in their own eyes, a boy taken as a hostage and turned into a disciple, a hero fighting for a child’s innocence. Sadly, McFarlane fails to capitalize on these ideas or turn them into engaging thoughts beyond mere surface-level observations. The depth is there, standing on the edge of a precipice. Unfortunately, close as it is to falling into something deeper, its feet are rooted to the edge, planted firmly by a gravity which McFarlane’s narration cannot overcome.