Spider-view: “Torment”

The first arc in Todd McFarlane's Spider-Man title is gorgeously visualized yet narratively underwhelming

—by Nathan on February 5, 2022—

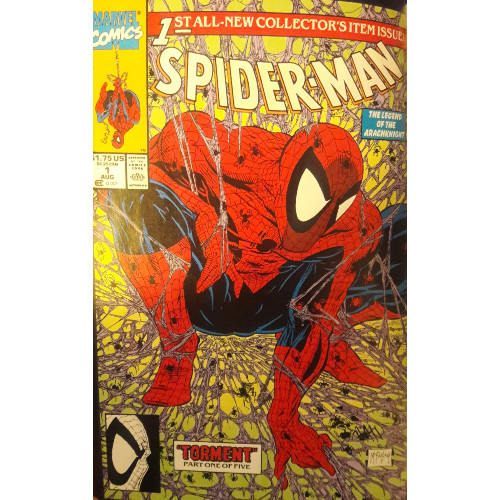

In 1990, superstar artist Todd McFarlane, known for his work on Amazing Spider-Man alongside David Michelinie (where and Michelinie introduced Venom) and his time on The Incredible Hulk with Peter David, was given his own monthly Spidey series to illustrate and write: Spider-Man.

Yeah, just “Spider-Man.”

Referred to jokingly as “the adjectiveless Spider-Man,” the title was a massive hit right off the bat, the first issue selling 2.5 million copies alone. A lot better writers than me have discussed the series’ impact on the comic book market and the ramifications from even this single decision–it was no doubt that having a McFarlane-led Spider-Man series (with, don’t forget, a bunch of variant covers) would inspire collectors to invest in the comics. But the notion of giving a creator a title and allowing that creator most of the creative control over its development, primarily a creator known for his fancy art over anything else, leads to interesting narrative decisions.

I want to examine McFarlane’s first arc, “Torment,” and see with what eye the famed artist approached the various aspects needed to tell a good Spider-Man story…and if he tells one.

“Torment”

Writer: Todd McFarlane

Penciler: Todd McFarlane

Issues: Spider-Man #1-5

Publication Dates: August 1990-December 1990

I’ve said elsewhere that the purpose of this blog is to primarily study Spider-Man stories themselves, not necessarily the history surrounding the panels and pages. In my original post outlining the purposes of this blog series, I mentioned how I’d rather avoid focusing on “background information.” I cited the “Clone Saga” as an example–when I get to reviewing that mess of a narrative, I don’t want to get hung up on the fact that Writer X discussed with Writer Y about making this decision or that decision. I do believe, however, that certain background details warrant examination…such as the fact that Todd McFarlane wrote and illustrated the first fifteen issues of this fourth ongoing Spidey title.

Based on “Torment,” I’d love to say McFarlane viewed Spider-Man as his baby, as a genuine canvas for his creative output. Maybe he did. Maybe I should give the guy credit for really sifting through the words and art to find the proper balance between the visual and the verbal. In certain instances, “the artist as writer” works well on a title. Jack Kirby’s original Eternal series is pretty entertaining, as is Walt Simonson’s stint on The Mighty Thor. Frank Miller showcases complete control over his narratives when writing and illustrating Daredevil and The Dark Knight Returns. Jeff Smith’s Bone is proof that a writer can also invent the world around him and not lose sight of a stirring saga.

I guess McFarlane isn’t any of those guys.

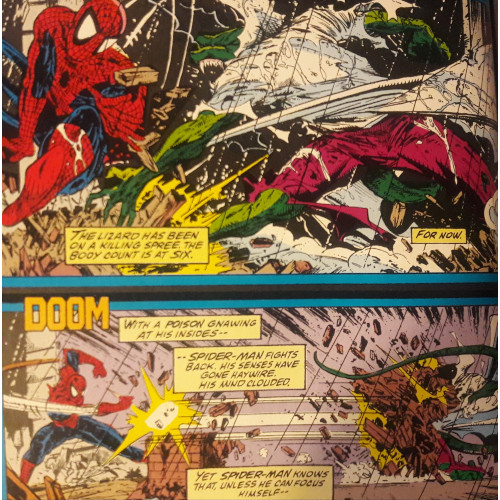

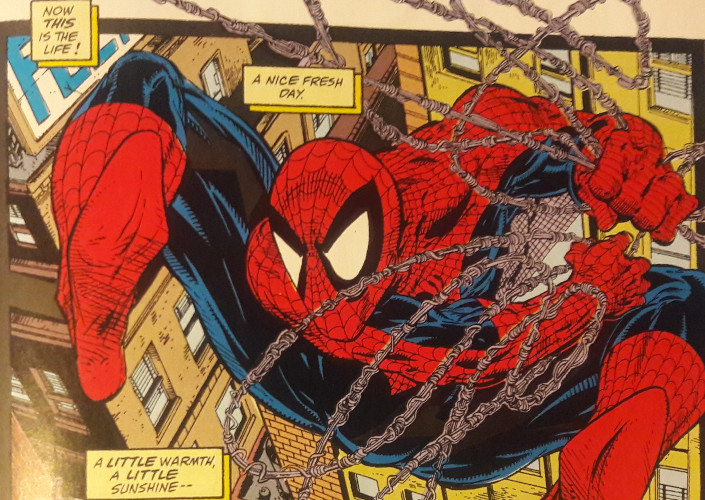

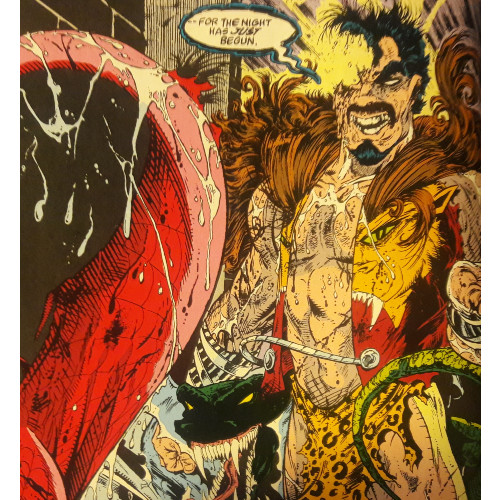

Naturally, the art is fantastic. McFarlane’s strength lies in the wonderful detail he fills his panels with. Spider-Man’s webbing is an interlaced bundle of fibers; you can follow the movement of individual strands as they coil around one another, each line distinct and defined. His Lizard is an overpowering mass of muscle and rage, a savage monster–perhaps, in my mind, one of the more animalistic depictions of the villain (and certainly the most animalistic at this story arc’s time of publication). McFarlane plays wonderfully with shadows and light, and as most of his story takes place at night, he artfully injects horror into his environments as well as his chracters. Dark streets and alleyways hide deeper shadows, blood drips freely, rain spatters the world in drops and runs in rivulets. The detail is incredible.

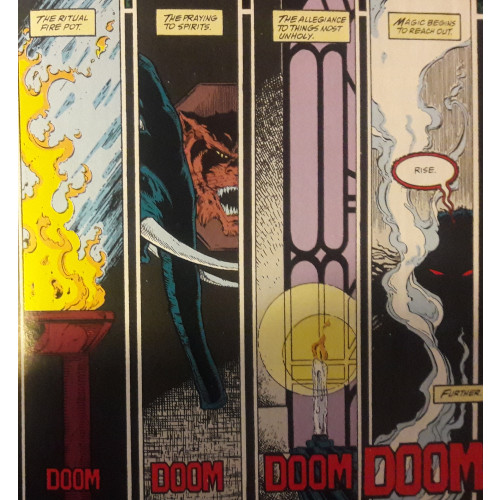

But McFarlane must also weave a narrative tethering these people, places, and particulars together, and this is where his pencil skritch-es along the pages. The story itself isn’t terrible by any means–the Lizard, mindlessly controlled by Calypso, a former ally of Kraven the Hunter, prowls the darkness, seeking Spider-Man. It’s a simple premise, yet McFarlane makes the whole thing work across five issues…mostly.

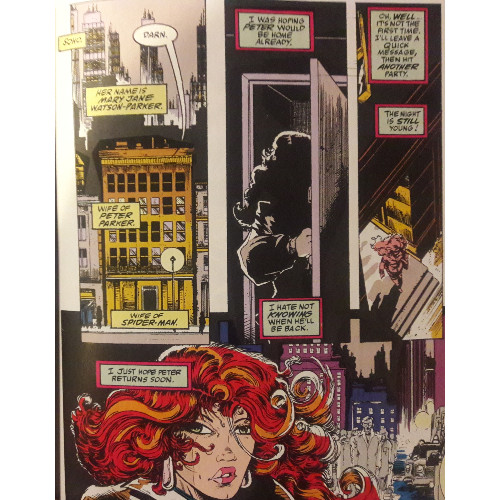

The first issue–the $2.5 million seller–is a lot of set up and goes by rather quickly. I actually surprised myself when flipping to the last page, hoping for a bit more meat than what I received (me and the Lizard both, I suppose). The other issues play off each other well, and McFarlane seems to better understand cliffhangers and tension as he goes along. But the first issue merely sets up the main players–Spidey, the Lizard, and MJ (Calypso comes later)--and saves the action for later.

The rest of the story worms well along, featuring some spectacularly illustrated action sequences between Spidey and his reptilian rival and decent pacing. Cliffhangers involve an exploding mansion (Kaven’s former residence), a seemingly resurrected Kraven the Hunter (a wonderfully graphic visual), and Spidey at the mercy of the Lizard’s claws. Interesting ideas are seeded here and there–Calypso’s hunger for revenge against Spider-Man, McFarlane utilizing this very minor villain to further Kraven’s post-“Last Hunt” story, is an interesting premise; her use of the Lizard taps into Curt Connors’ scaly alter ego’s more violent nature; attempts are made to draw contrasts between our web-swinging hero and his darkness-dwelling foe. And, if this were merely a series of visuals, you’d get that. From an artistic standpoint, McFarlane totally controls the story. He times the plot beats well, puts Peter in grim situations, plays up the horror of a murderous lizard monster and a zombie-fied Kraven.

But then McFarlane opens his mouth, and the visuals are hampered by a series of half-formed thoughts, weak dialogue, and mindless narration. I don’t think McFarlane is being lazy or thoughtless–I think he’s trying to make a point and attempting to draw connections between characters. In execution, unfortunately, the idea doesn’t work.

“Rise above it all” is a mantra McFarlane returns to repeatedly, tagging each splash page with the phrase and connecting it to New Yorkers, Spidey, and the Lizard. It’s an attempt at commentary, weaving in this concept of asserting one’s self, moving past tribulation, rising against tides of difficulty. Yet the awkwardness of the phrase, particularly in McFarlane’s stilted methods of leading up to the words in each issue, cuts off most attempts at poetry or pithiness. Just the word “Rise” may have sufficed or an inclusion of “Torment,” the narrative’s title. “Rise above it all” just doesn’t read as well, and instead of becoming associated as a strong, poetic tether to each of the issues, ends up limping its way through each appearance.

The concept of “rising” works visually at moments–the Lizard rises from the depths of the East River in a shower of water, spittle, and snapping teeth; Spidey is forced to scramble from a mound of rubble (where McFarlane draws a fantastic comparison between Spidey’s current predicament and the grave he dug himself out of in “Kraven’s Last Hunt") after a defeat at the Lizard’s talons; he later escapes the wreckage of a burning building. But, as I mentioned earlier, this only works from a visual standpoint. The words are redundant instead of additional, merely copying the visuals' underlying meaning without deriving anything greater from them.

As I said, McFarlane isn’t being lazy…you can tell he’s really trying to insert ideas and notions. The “rise” mantra seems like his attempt at creating a verbal connection across issues, his consistent reference to Spidey as “a hero” or “our hero” tries to draw the reader in, and even how he maneuvers between speakers–Spidey’s thoughts, MJ’s thoughts, Calypso’s backstory, an omniscient, second-person narrator–may be a nod to “Kraven’s Last Hunt,” which used a similar method. But where J.M. DeMatteis’ dialogue felt intentional, where characters were fleshed out and voices were unique, McFarlane’s dialogue and speakers feel jumbled, not fully realized. It’s like he threw whatever words he wanted into his script and went with the rough draft.

The same can be said in how he tries moving his characters through the plot, particularly Spidey and MJ. McFarlane brings a base understanding of the characters and their relationship, which isn’t an uncommon occurrence. As I’ve noted previously, both Christopher Priest (as Jim Owsley) and David Michelinie have struggled to incorporate MJ meaningfully in their stories. McFarlane uses her in as simple a fashion as possible, having MJ juggle between worrying about Peter and going out partying because, what the heck, her husband’s Spider-Man! He’ll be fine! You glean no new understanding about MJ through her evening escapade as Spidey fights for his life. McFarlane’s version isn’t supposed to be as cold or thoughtless as Priest wrote her–if anything, I believe you’re supposed to see MJ as confident in Peter’s capabilities. But McFarlane’s execution is not satisfying, making me mentally wrestle with whether MJ really is that confident in her husband or actually a hint careless.

This new, adjectiveless Spider-Man title was supposed to be a premier series, casting one of comicdom’s favorite hot artists in the role of superstar, giving him the chance to control the ins and outs of a narrative rather than delivering art for another writer’s story. From an illustrative standpoint, McFarlane soars, bringing a bit of horror to the world of Spider-Man and drawing a dark yet detailed New York. His story, on the surface, is nicely tethered to “Kraven’s Last Hunt,” is paced fairly well, and utilizes good tension to keep the reader interested in the developing plot. But McFarlane’s words–the method in which he conveys his plot and his cast’s internal thoughts and drama–often fail like an empty web-shooter. His prose is basic, unable to fully grasp the depth of these characters or offer little understanding beside their base personality traits. He stabs at deeper notions but fails to thread unique character connections effectively through the entire piece. For a story that consistently notes a sense of rising above, “Torment” tends to stay beneath the surface like a gator, waiting for easy prey to come along.