Spider-view: “Kraven’s Last Hunt”

This J.M. DeMatteis-penned classic remains a deep, engaging exploration of one of Spider-Man's original enemies

—by Nathan on March 24, 2021—

When people talk about Spidey’s greatest storylines, “Kraven’s Last Hunt” is reverently spoken of in the same breath as “The Night Gwen Stacy Died,” “The Kid Who Collects Spider-Man,” Amazing Fantasy #15, "Nothing Can Stop the Juggernaut," and “The Death of Jean DeWolff." A celebrated epic among Spider-fans, KLH has stood the test of time and, as stories such as “The Grim Hunt” and Nick Spencer’s “Hunted” no doubt attest to, continues to influence the modern Marvel mythos.

But setting its legacy aside for a moment, I want to dive into the story itself—as countless others have done before me—and zero in on what makes this particular tale tick. Why is this so beloved by Spidey’s readers worldwide? Why, even thirty years later, does “Kraven’s Last Hunt” routinely top lists of favorite Spidey stories? Though I cannot answer for the collective fanbase, I can certainly save a word or two on my own behalf.

So put on your favorite lion fur vest and leopard print pants (all the REAL fans have ‘em) and help me claw our way through one of Spidey’s darkest adventures to date.

“Kraven’s Last Hunt”

Writer: J.M. DeMatteis

Penciler: Mike Zeck

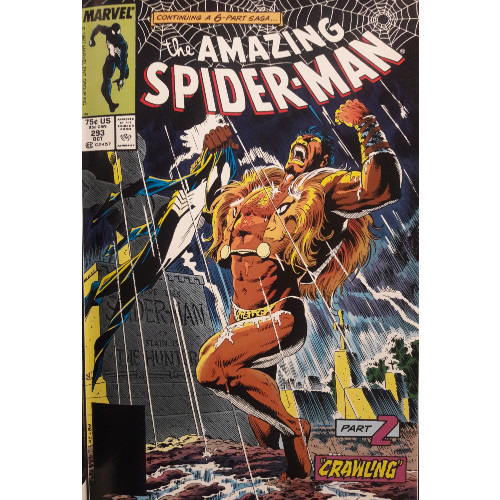

Issues: Amazing Spider-Man #293-294; Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man #131-132; Web of Spider-Man 31-32

Publication Dates: October 1987-November 1987

J.M. DeMatteis, in my mind, stands head and shoulders above most of his contemporaries when we’re talking about Spidey writers of the 80s and 90s. Several of his stories focus more psychologically on characters, especially villains, digging into their intentions and motivations fantastically and displaying a depth of personality few writers achieve. While stories like the three-part “As Dreams Are Made On…” or “The Gift” admirably showcase DeMatteis’ talent (as I hope to discuss someday), “Kraven’s Last Hunt” is arguably his finest work.

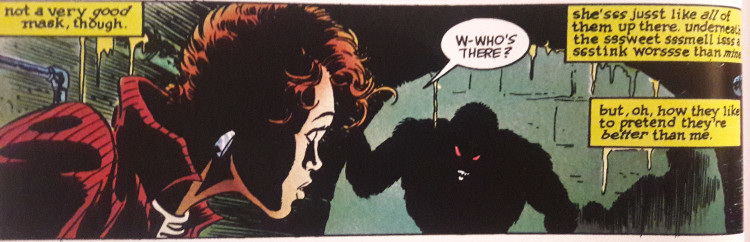

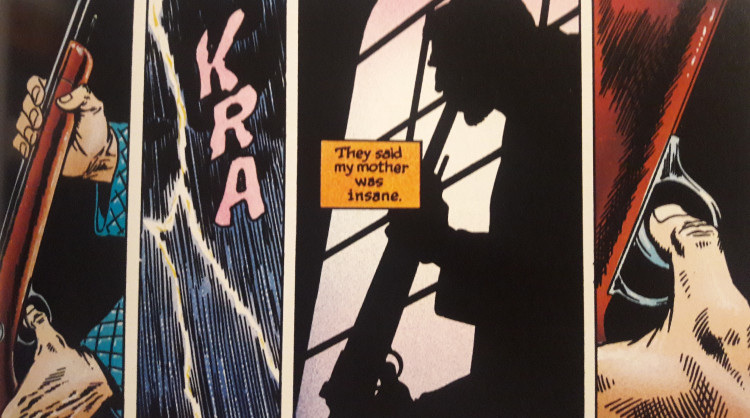

Unlike those aforementioned stories, DeMatteis dramatically plays with dialogue and narrative throughout the story. We get at least four separate character POVs throughout the tale—our hero Spidey, his newlywed wife Mary Jane Watson, our villainous Kraven, and the animalistic Vermin—and I’d argue there are moments when a fifth POV appears, representing a division between Peter’s conscious and subconscious. This interplay of perspective is used to beautiful effect throughout the whole story; through each lens, we are offered a unique look at events as they unfold.

Peter is less the hero of the tale as he is a victim of events going on around him—his perspective is latched onto concepts of death, including fear of his own and those around him (some of whom have recently passed, such as Ned Leeds, and others who are still alive and dear to him). Mary Jane serves as almost an “everyman” throughout the story, giving as a fantastic glimpse into a new side of Peter’s “power and responsibility” mantra. Peter’s married to MJ now, he has a new responsibility in the guise of a wife to love and care for, and though scenes of MJ longingly looking out a window while Peter’s away or wishing Peter could save her from certain grim situations may seem flat, they in fact point to an interesting character dynamic: she isn’t just a new bride waiting for her husband to return from work; she’s been pulled into Spidey’s life as a superhero and, alongside her husband, will witness the pain and bear the trauma of the lifestyle he leads.

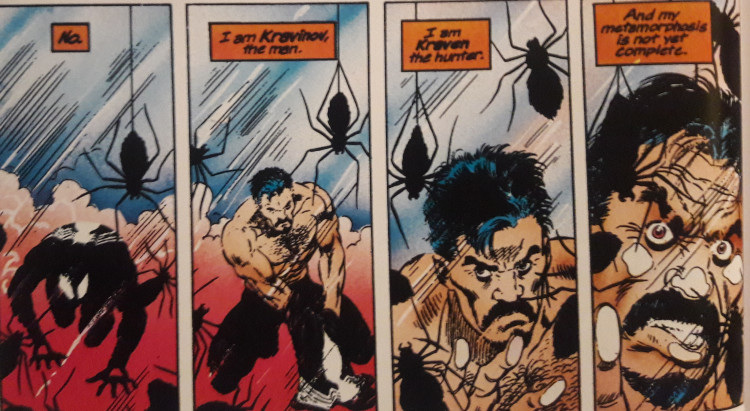

As the villain of the story, Kraven is offered a new level of depth I don’t believe readers had yet seen from him. DeMatteis introduces a nationalistic aspect to the hunter, a furor buried deep within Kraven’s psyche and driven by his family’s ties to the old country, Russia. Kraven is, certainly, hunting Spidey in this tale because the hero is the one prey who has always evaded him; but even deeper than that, in Kraven’s mind, Spidey represents the twisted lack of honor and dignity that has consumed civilization. Kraven represents one ideal (whatever honor he found in the old country) going out and “killing” a contrary ideal (Spidey representing the lack of dignity in Western civilization) and then proceeding to replace those corrupted principles (shooting, burying, and then becoming Spider-Man). That’s probably simplifying it a tad too much, but the part to focus on is that the “Spidey vs. Kraven” conflict gets elevated from a “hero vs. villain” tussle to a “philosophy vs. philosophy” battle. It isn’t a concept used much moving forward in their relationship, but for this story, it alters Kraven from a gimmicky villain to a well-written antagonist.

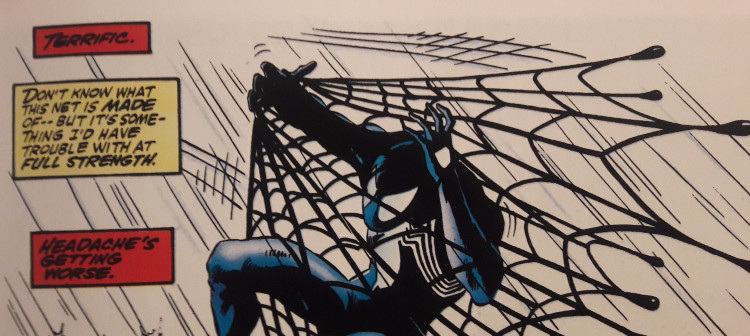

Vermin, though a very minor character, also plays an interesting role in the tale. He serves as Kraven’s final “test,” if you will. Introduced in Marvel Team-Up #128 by DeMatteis, Vermin was defeated by the combined might of Spidey and Captain America. By going after and capturing Vermin on his own, Kraven proves a level of superiority over Spidey (no, not like Doc Ock—we’re not going there just yet). Their battle is beautifully fluid: Mike Zeck’s pencils bring every moment of the fight to life, and details such as metal pipes, dirty sewer water, even torn costume fragments wonderfully complement DeMatteis’ dialogue and inner monologues. Zeck is illustrating a much darker narrative than Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars, and his work for KLH is a nice comparison to his popping alien backgrounds and colorful characters from that ensemble crossover.

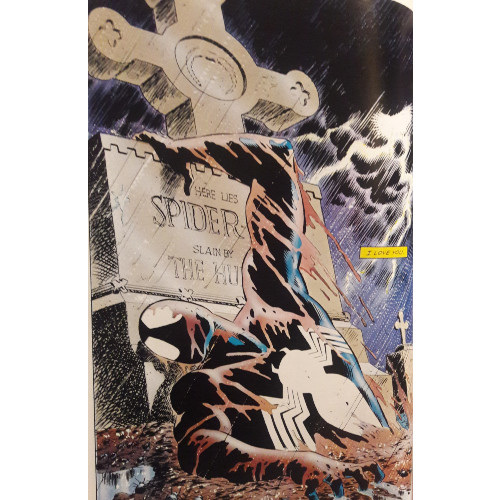

Speaking of the art, so many story beats in this six-parter have become classic images for fans, courtesy of Zeck: Spidey getting shot by Kraven; Spidey being buried alive; Kraven assuming the role of Spidey and going ape on thugs while clad in a black costume; Spidey valiantly breaking through the rain-soaked dirt and freeing himself from the grave; Kraven shooting himself at the end of the story’s fifth chapter. Zeck handles the subject matter gracefully, bringing in as much visual darkness as necessary. His backdrops are dark, often laden with clouds or rain; his characters are grim; his action scenes show a heightened brutality to give you the full weight of Kraven’s evil. It’s one thing for Spidey just to say that Kraven’s “out of his mind”; it’s another for him to say it while the reader can see Kraven pulling his widest J. Jonah Jameson-imitation smile, the barrel of a shotgun aimed right at our hero’s head. Not only is DeMatteis’ script complimented by Zeck’s artwork, it’s validated by it.

Kraven’s death is also worth discussing. Back in 2010, when “Grim Hunt” first released, I was ecstatic that writers were bringing back the long-deceased villain. And, sure, we could get into the whole “nobody really stays dead” conversation, but I’d rather focus on the fact that an impactful Spidey villain was returning to the stable (so what if he disappeared from ASM for nine years afterward?). I don’t think, however, that Kraven’s resurrection demeans his death in KLH. In the 21st century, perhaps Kraven’s rhetoric about Russia and civilization isn’t as meaningful, and perhaps that side of him has been lost since his resurrection, but in the context of KLH, his death (and the reasoning behind it) carries decent weight. Kraven finally defeated Spider-Man. Spidey eventually unburied himself and reclaimed the mantle, but to Kraven, none of that mattered. Forget Doc Ock and the Green Goblin and all those guys who want to kill Spider-Man for the sake of getting him out of their way or because they hate that pesky wall-crawler oh so very much. At the time, none of them had “beaten” or “supplanted” Spidey the way Kraven had. And with that mission finished—with a total victory that, as DeMatteis’ dialogue shows, is completely justified through Kraven’s warped perspective—the Hunter fires his gun one final time.

Well, okay, not “final” final, but in 1987, it was pretty significantly settled as “final.” Kraven was kaput.

He “killed” the Spider; he became the Spider. It was all Kraven needed to do, and it was done.

Needless to say, “Kraven’s Last Hunt” isn’t intended to be a happy tale. It’s purposefully designed to make you think, to look at these characters in all their complexity and wonder about them. You see Peter’s fears come to life as his worries regarding death hit too close to home when Kraven drugs and buries him for two whole weeks; you watch MJ’s fears unfold as she brutally takes her own dread out against a rat in her apartment home; you watch Kraven’s descent into madness as he literally consumes spiders even before he metaphorically consumes one; you behold Vermin’s worries about the world and, even though he’s not the nicest of characters himself, you pity him. Important as the overarching storyline is, and as impactful as it has been over the last thirty years of comics, it’s the characters who bring the tale to life. Their interplaying narrative threads, woven together in rich and complex ways, show a level of consideration for the story that few other writers can hope to achieve.