(Strand)om Stories: Weapon X Review

Barry Windsor-Smith's seminal tale successfully explores how the man named Logan became the berserker called Wolverine

—by Nathan on January 31, 2021—

I’ll be the first to admit that this “tether” is a really, really big stretch. As I’ve stated previously, the purpose of this particular series is to blog about stories which don’t fit within my Spider-view timeline but are tales I want to blog about anyway. Yet, the one qualification I mentioned in the first (Strand)om Stories post was that some sort of connection, however tenuous, will probably exist. So how’s this for a loophole? In previous posts, I’ve examined X-Men stories and an Iron Man tale, the latter penned by David Michelinie, a frequent Spidey writer. The final chapter of that Iron Man narrative was illustrated by Barry-Windsor Smith, who provided the words and pencils for Weapon X, which I am reviewing here. It’s a bit of “six degrees from Spidey'' situation, but I’d like to review this tale, so I’m letting it slide.

From his first appearance, Wolverine was a man of mystery. Questions buzzed about where he came from, what his real name was, what exactly his background was...over the years, tidbits were dropped. Chris Claremont, if I’m correct, was the first person to name him “Logan” and established the pint-sized prowler as a member of the same Canadian military group that James Hudson (Guardian of Alpha Flight) belonged to. I couldn’t tell you all the details Marvel writers released over the years, but I do know this: Weapon X is a treasure trove of facts for any fan wondering how exactly Logan transformed into the Wolverine.

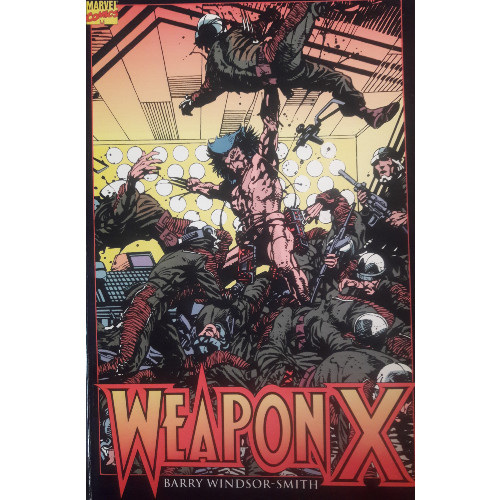

Weapon X

Writer: Barry Windsor-Smith

Penciler: Barry Windsor-Smith

Issues Collected: Marvel Comics Presents #72-84

Volume Publication Date: April 1994

Issue Publication Dates: March 1991-September 1991

Before I begin, I should note that other volumes collecting this story exist, specifically tomes published in 2008 and 2020; however, all these volumes cover the same issues, so there seems to be no difference between any edition of this particular narrative. I purchased mine as a set of Wolverine volumes, which also included Old Man Logan, so I won’t complain.

Not to damage my credibility, but I should remark that I’ve always had a soft spot for the much-maligned X-Men Origins: Wolverine movie. I’m not terribly fond of Deadpool as a character overall, so seeing him cannibalized in bringing Ryan Reynolds’ sewn-lipped nightmare to the screen never fazed me much. Regardless, that film doesn’t hold a candle to Barry Windsor-Smith’s twelve-issue extravaganza.

This is the story that Origins could (and should) have been.

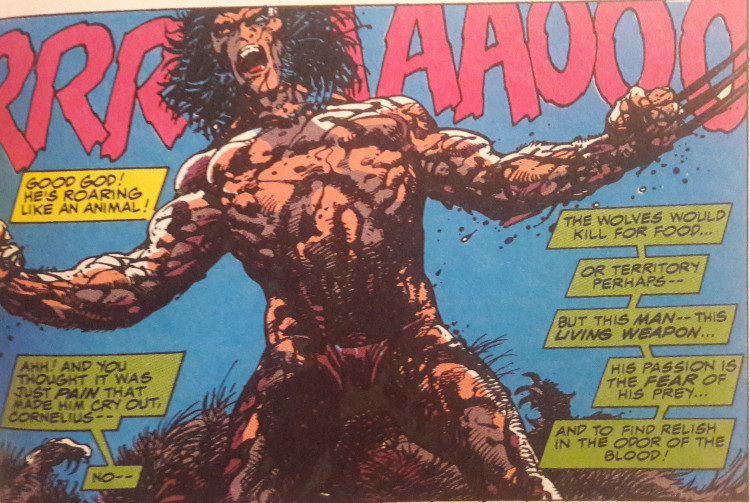

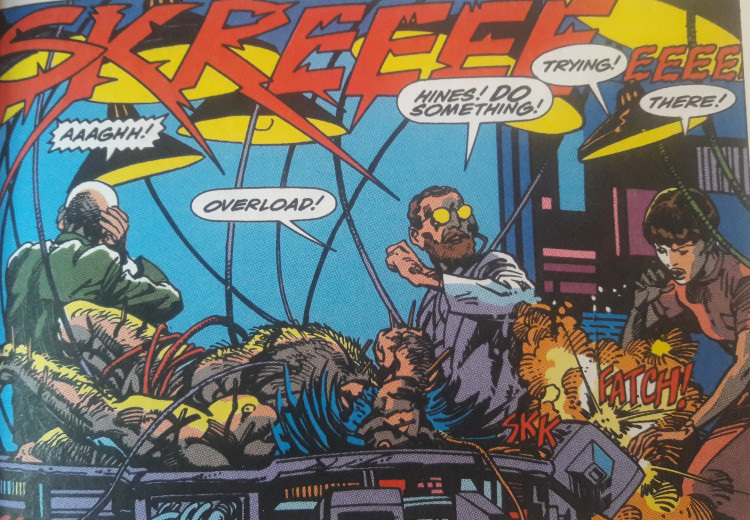

The comic is drenched in injustice, from the moment Logan is kidnapped, to the various procedures run on him, to the tests he’s put through, to the final sequence that sees him go absolutely berserk. Here’s a guy, living a normal life, who is one day violently yanked off the street so a bunch of dudes in lab coats can brainwash him into becoming an assassin. It’s evil, pure and simple. Windsor-Smith makes it absolutely clear that you’re supposed to empathize with Logan. “What have you done to me?” the mutant shrieks in agony at one point after being bombarded with needles and tubes and fluids. The scientists working on him, though occasionally not without compassion, force day after day of trauma upon Logan, striving for results.

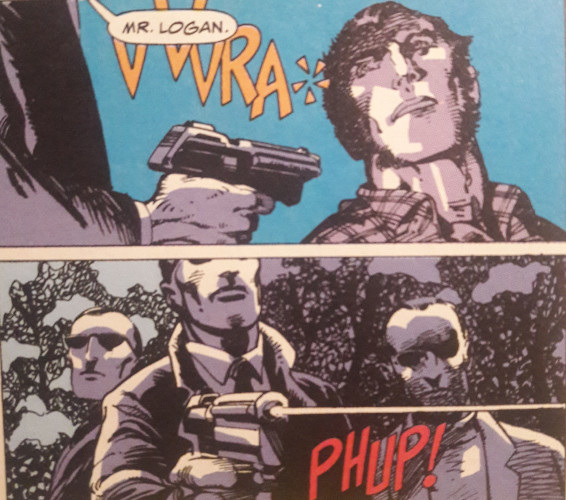

It’s a remarkably different way of viewing the character. For much of the story, Logan comes across as helpless, unable to alter his situation or free himself from captivity. You have to remember that he’s not the merciless fighter or mutant superhero he'll become known as just yet. He’s just a man with long, sharp bones that pop out the backs of his hands and, hey, someone thinks they’d look real nice with a shiny, chrome finish.

Even when Windsor-Smith enables Logan to cut loose--for example, in a scene where he goes up against wolves--that helplessness remains. Logan acts, not of his own accord, but at the whim of these scientists, doing whatever tasks are assigned him and oftentimes being outright controlled. Heck, at one point, the guy goes up against a bear in a short yet nifty sequence. Even then, even as Logan decapitates the grizzly before it can chow down, there’s little sense of victory. It’s a cool scene, one of the most memorable in the whole story, but it’s further proof of Windsor-Smith’s premise: Logan has lost control, and not in a “crazy berserker” kinda way.

The closest any film has gotten to properly depicting Logan’s captivity (and subsequent freedom) is X-Men: Apocalypse, where he bursts free and wreaks bloody vengeance on the complex holding him. But even that film only gets it partially right. What movies fail to realize about Logan’s experience as a guinea pig is the trauma associated with his time in the program. Origins has him escape as soon as he receives his adamantium claws, forgoing the agonizing preparations before the procedures and months of tests afterward. Apocalypse shoehorns in a rampaging Wolverine because, hey, Wolverine’s cool when he’s gutting people, forgetting how much of a victory he experiences when he’s finally free.

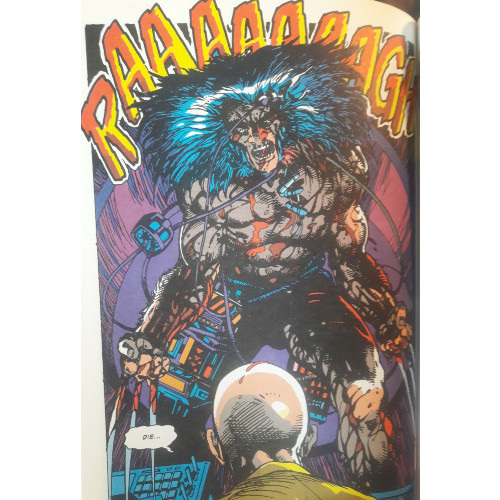

At the risk of spoilers, I’ll say this: Wolverine does leave the program, and though it’s sort of in the way you’d expect, it’s not necessarily a massive bloodbath. I mean, there’s a bloodbath, but Windsor-Smith plays with your expectations. When Wolverine breaks free, it’s much more cerebral than you’d imagine. He doesn’t just kill his enemies, he makes them realize that any control they once believed they had is now gone. It’s far more liberating than seeing a guy run down a hallway, cutting down soldiers.

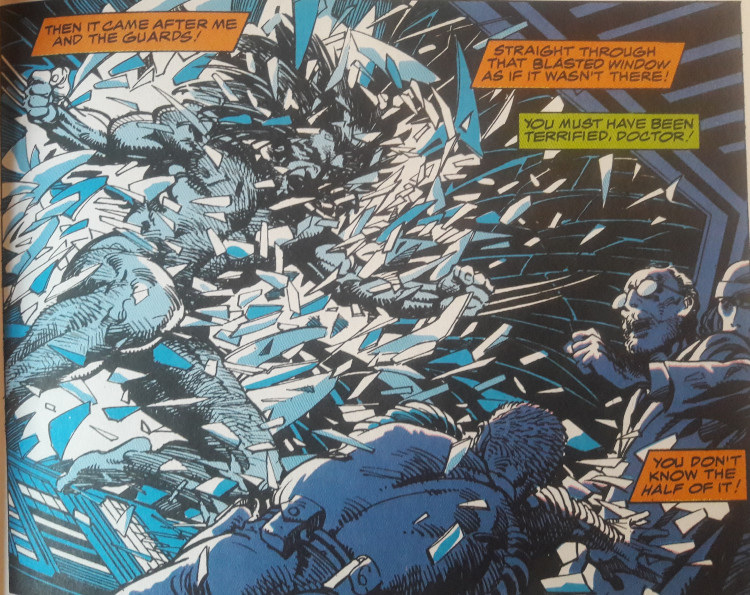

But people die. Windsor-Smith dedicates about a fifth or so of the story to an incredible sequence where Wolverine just up and rampages. He steers the comic towards horror, and for the first time in the story, you maybe question Wolverine a little. You start to wonder if maybe he’s going too far. Visually, the sequence is wall-to-wall action, reminiscent of a horror movie. Wolverine becomes more than a man or mutant; pushed to the edge, he embraces his animalistic ferocity. It’s like watching Alien or Jurassic Park, seeing the small humans against something other (or perhaps inhuman) they thought they could control. Is it violent? Yes. But is there satisfaction in knowing the Wolverine on the hunt? Morbid as it may sound...yes.

Even then, though you don’t necessarily cheer on the scientists, you certainly feel for their situation. Doctor Cornelius has enough of a conscience to at least question his superior, to wonder about the morality of it all. Yet he’s also a busy worker bee, a “yes man” who puts his morals aside when it comes to matters of obedience. Ms Hines, a personal assistant more than a scientist, feels more like a victim than anyone else. Maybe she chose to be part of the Program or maybe she got roped in (Windsor-Smith never clarifies), but she certainly exudes a more compassionate persona toward Logan than her compatriots.

But Professor Thorton...he’s the man you love to despise. Ruthless to the core, he pushes his agenda and pushes Logan and his subordinates. Occasionally, he wades into murky, cliche “mad scientist” territory, his dialogue coming across as a little wonky. Of the three “human” characters, he is also the least we learn about. No background, not even much in the way of personality aside from his blind fanaticism. Still, he’s easy to hate.

Visually, Windsor-Smith possesses complete control over his narrative. His dialogue boxes and speech bubbles in particular are fascinating to watch, especially when he deviates from a standard “left-to-right” reading pattern. Dialogue boxes can work their way in an almost semi-circular pattern up certain panels, making for a disjointed but entertaining reading experience. I never found myself questioning why he chose to place certain boxes where; instead, I was intrigued enough by the pattern itself just to enjoy what he was doing. Windsor-Smith’s detail is incredible, especially his backgrounds. The Weapon X lab, though it never fully feels like a truly “lived in” environment, is still filled with doodads and monitors galore. It’s "creepy underground bad guy/government institution base" to the max.

I did take issue early on with Windsor-Smith’s narrative: Logan’s kidnapping is described as almost coincidental, that the scientists simply targeted a military operative with good fighting instincts. The scientists are, in fact, surprised by Logan’s healing factor, shocked when his claws pop out for the first time, astonished that he’s a mutant. I wish Windsor-Smith had leaned into the idea that Weapon X “conscripted” Logan because he’s a mutant. The concept that Weapon X finds out about Logan’s other beneficial attributes seems a bit difficult to swallow. “Oh, look, the guy we picked for our assassination program just so happens to have claws! And animalistic rage! And he can shrug off bullets! This is better than we planned! 11/10!” I believe it would have made more sense for the Program to see those desirable traits in Logan and take him for that reason.

Beyond this complaint, Weapon X deserves the praise it receives for being a rather famous Wolverine story. It’s often spoken of among other tales such as Old Man Logan and Chris Claremont and Frank Miller’s original Wolverine miniseries. Barry Windsor-Smith, fully in control like a calm Wolverine, does the best he can to craft a well-told, eerie, yet sympathetic portrayal of Logan. It’s certainly an origin story for the character, displaying his transformation into one of fiercest fighters in the Marvel Universe. But, as we’ll hopefully see soon, it’s not the only origin story for our metal man.