Distinguished Critique: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns Review

Frank Miller's famed, dystopian series redefines and revitalizes the Batman, shaping a new world around an old hero

—by Nathan on May 3, 2023—

Even superheroes get old.

One of the most interesting aspects to comics is how publishers handle time. Characters such as Superman and Batman have been around for eighty years, yet Clark Kent and Bruce Wayne have not become centenarians. They’re still young, healthy, in their prime. Comic book universes stretch out the aging process, keeping their prime characters as youthful as they can for as long as possible. Who’d been interested in reading the adventures of a ninety-year old Spider-Man for the next ten years?

But even superheroes get old.

Every so often, a story will veer off deep into the future, examining how our heroes would behave if they actually did age significantly. Old Man Logan saw a wrinkled Wolverine swearing off his claws...at least, momentarily. The recent Spider-Man: Life Story examined how Peter Parker’s life could change if he aged as the years progressed. And then there’s the father of all “old superhero” stories...or maybe the “grandfather.”

Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns.

But Miller’s magnum opus isn’t just the tale of a wizened and worn Bruce Wayne. His series is an examination of the changing face of superhuman narratives in the 1980s and how the perception of superheroes themselves was morphing in the public conscience. Miller’s story is heralded, along with tales such as Alan Moore’s Watchman and The Killing Joke (and, I'll attest, to an equally impactful but lesser publicized extent, Mark Gruenwald’s Squadron Supreme), as a lynchpin for darker, grimmer superhero narratives, particularly those over-the-top globs of excess which would dominate the industry in the 90s. Regardless of its legacy, Returns remains perhaps the most well-defined Batman story of its or any other generation, a grim gaze into the face of Gotham and a redefinition of her endearing first son.

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

Writer: Frank Miller

Penciler: Frank Miller

Inkers: Klaus Janson, Todd McFarlane

Colorist: Lynn Varley

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: The Dark Knight Returns #1-4

Publication Dates: June 1986-December 1986

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

Miller’s opening issue is, in my mind, one of the single greatest issues of comics I’ve read, a standalone favorite up there with Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1. Yes, it's the first chapter of a four-issue saga, but if you disassociate the issue from the rest of Returns, it remains a perfect reintroduction to Bruce Wayne and the idea of Batman. Miller’s series was published at a time when Batman was still associated with the more colorful, campy show led by Adam West. Returns swooped in, shook that version up, and dipped him in tar. No longer was Batman a gimmick or a goofy live-action cartoon.

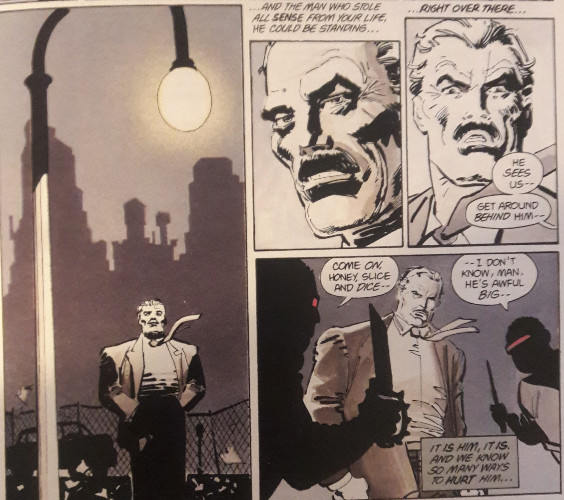

What’s perhaps most impressive about the series, particularly in how Miller starts his story, is how it presents the Batman/Bruce Wayne dichotomy. “Batman” is frequently referred to in animalistic terms, growling within Bruce Wayne. Retired for several years after the death of Robin, Batman has been subdued, suppressed. In one of the inaugural issue's first pages, Bruce finds himself drawn back to Crime Alley, where his parents were murdered before his eyes years before. As he ruminates on the past, he’s assaulted by a pair of thugs from the “Mutants,” a gang which has overrun Gotham (and have no association with the X-Men). He doesn’t fight back. Despite the howling in his gut, Bruce ignores “Batman.”

Miller expertly pulls Batman out of retirement as the pages build; at first glance, some might believe Bruce simply dons the cape and cowl again to battle this new “Mutant” menace, but such an interpretation misses a key aspect: the Mutants are merely the method through which Bruce steers his righteous anger. What brings Bruce back to the bat is the overwhelming sense of dismay and disgruntlement towards what his city has become, twisted with perhaps a touch of guilt. The impetus for Batman’s return is actually Harvey Dent, who, despite years of therapy to heal his internal turmoil and plastic surgery to fix his external scars, turns back to crime as Two-Face. The mission isn't over. It was never over. Bruce has just finally admitted it to himself.

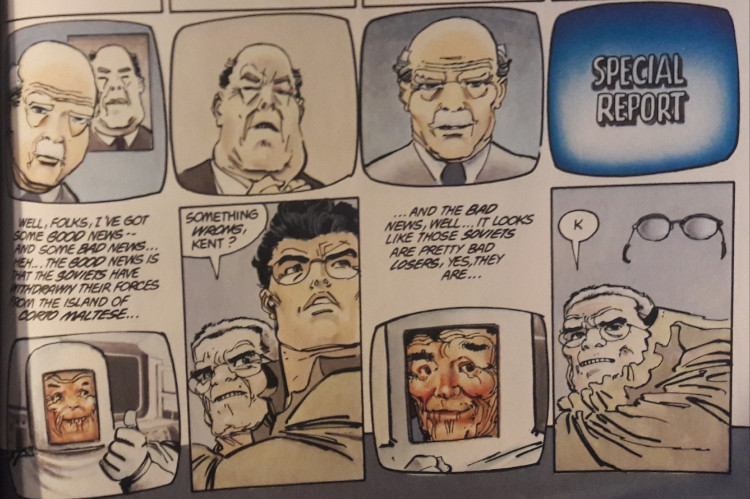

Years before, Bruce retired, gave in. And, over time, Gotham has fallen prey to darker minds. Batman returns to shove the darkness back. Yet it’s a newer world that Batman finds himself in, and Miller capably crafts a strong, realistic realm for our Caped Crusader to be reborn into. We’re sucked into an 80s-style era where the Cold War wages on, Russia threatens the U.S. with a giant EMP missile, and Ronald Reagan dithers on about unity and fortitude while hiding behind the safety of a television. Media itself plays a massive role throughout Miller’s story. Television screens and newscasters pop up in supporting roles, always giving their spin on a breaking story. Humor and tragedy alike flicker across the screens, with Miller’s talking heads barely affected emotionally from any outcome. One newscaster placidly remarks they have footage of a bomb going off in a subway; two others who get into a verbal argument are shushed by a third, trying to keep tempers even.

A sense of bizarre realism weaves its way through the series, particularly in how news is disseminated. You’re treated, at moments, like an audience member, like a Gotham citizen tuning into the evening news. The broadcasts allow Miller not only a way to convey his personal rhetoric but to frame certain sequences: bits of plot and subplots are verbalized by news reporters, such as the fact that incoming GCPD commissioner Ellen Yindel has saved the life of a senator, an event hinted at earlier. Gothamites themselves are frequently on screen, describing their view on events. It’s a bizarre yet satisfying form of manipulation that Miller wields. You, the reader, are given glimpses into events as they actually happen–such as the return of Batman or his final fight with the Joker–while being readily subjected to the subjective perspective of regular citizens. These Gotham City inhabitants are colorful and varied, offering a variety of outlooks, often contradictory, even to themselves. Interviews catch men and women behaving and speaking in ways contrary to how they frame themselves. Each segment flows into the overall plot, but Miller also makes these sequences engaging reading on their own. Not every scene is centered on Batman, but these moments add a well-rounded and lifelike feel to the narrative.

“Time” and “age” become highly important themes. Miller's Batman is old, a little creaky, somewhat rusty as he restarts his vigilante career. Yet his bravery and endurance blossom as they did when he was younger, and even if his methods have changed, his mission remains the same. He uses a gun to save a little boy; he utilizes a tank to scatter mobs of Mutant gang members (don’t worry, it's loaded with rubber bullets); he momentarily contemplates killing the Joker and ending their war forever. This Batman is certainly darker, but he’s couched within his era. The world outside has grown darker while he’s been away; he must grow darker to match. Regardless, his purpose and identity remain as rigid as they’ve always been. He’s here to save Gotham.

Finality runs wonderfully through the entire series, especially as Miller builds an alternate universe where anything is possible. His world doesn’t need to bend to continuity or the further adventures of our Caped Crusader. Though the series ends on somewhat of a cliffhanger, or at least a promise of tales to come, we see definite endings in various plot points. Commissioner James Gordon retires, replaced by a younger, more capable (yet anti-vigilante) officer. Batman and Joker’s battle is their last, with the Clown Prince of Crime dying at the end of the titanic struggle. Two-Face is healed from his scars. And a showdown between Superman and Batman is definitive, not hampered by fans quibbling over who’d beat who in a fight. Miller, free from the constraints of an ongoing series or maintaining continuity, is allowed to manipulate facts and definitions.

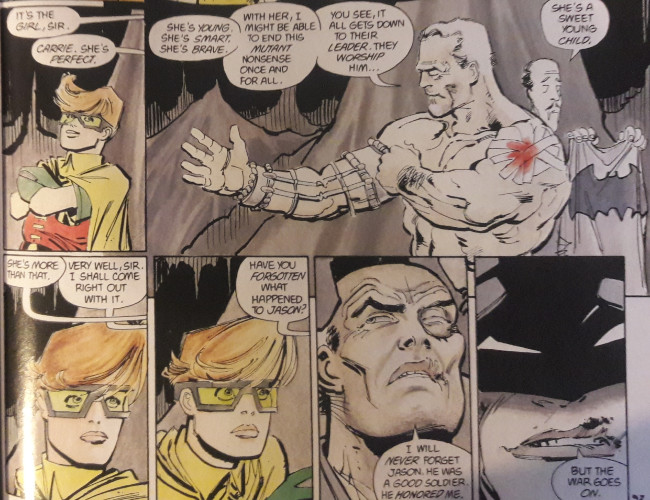

Miller makes interesting insights, especially when read in comparison to other stories published around the same time. Though written a few years before “A Death in the Family,” Miller, almost prophetically, utilizes the death of Jason Todd to knock the wind out a younger Batman's sails. Additionally, Miller lists Gordon’s wife as “Sarah,” a character he created a year later in "Year One," foreshadowing the dissolving relationship between Gordon and his then-canonical first wife, Barbara Gordon. Miller, particularly with his view on Robin, possesses the creative ability to rethink and restructure the world around Batman and his supporting cast. It’s logical that the death of a sidekick would propel Bruce into retiring the cape and cowl. It’s logical that Harvey Dent could be (at least physically) healed from his scars.

What makes Returns so much fun is how willingly Miller leans into this alternate universe concept, constructing these historical alterations or logically presupposing certain changes. You never feel as if Miller has gone too far or is bandying about too many ridiculous, implausible ideas. These changes feel organic, and even if Jason Todd had never been murdered in actual DC continuity (and, yes, I know he came back), the idea of his death feels plausible. It’s not like Miller introduces some bizarre notion that feels completely out-there–like, say, the Penguin becoming a point guard for the Gotham Knights or Mr. Freeze becoming a used car salesman. Miller seems to be asking, “If A, then B?” “If Harvey was healed, would he be reformed?” “If Robin died, would Batman retire?” “If Batman came out of retirement, how would the Joker respond?”

Miller’s narrative and themes point to the altering landscape of superhuman fiction. This wasn’t the 60s, where heroes bopped baddies with a “BIFF!” Gotham is grounded, torn apart by slavering madmen and feeble politicians. Batman doesn’t swoop in on a bat-line to bring the Joker into the revolving door system that is Arkham Asylum. Here, the Joker dies. Here, the public quibble over Batman as easily as they quibble over the particulars of their lives. Here, Superman has sold out and become a government stooge. Here, Bruce Wayne and James Gordon and Harvey Dent have reached the ends of themselves, supplanted by younger threats, younger monsters, younger cops, and younger heroes. Real change, typically ugly and grim, screeches at the reader like a rabid bat. Miller’s domain is fluid, altering, ready to change course at the writer’s whim.

Yes, The Dark Knight Returns made the Batman dark(er), but it did so by positing what the Dark Knight Detective could evolve into–or, as Miller seems to imply, what he needed to evolve into. Perhaps the problem moving forward, into the 90s, was making everything dark then and there, in the present. Miller’s Batman is gritty from time, roughened and weathered with age. His is a world that has been beaten down, scarred, blistered, and broken. It certainly looks a bit like ours–people arguing on TV, citizens disseminating their opinions every chance they get–but maybe it’s supposed to be a tad worse. And Batman simply compensates for the urban jungle he trawls through, fighting fire with fire.