Distinguished Critique: "Batman: Year One" Review

This Post-Crisis reframing of Batman's origin is definitive and impactful, offering clever insight into the new life of Bruce Wayne and his supporting cast

—by Nathan on April 26, 2023—

Every now and then, a long-running series with an accumulating issue count and decades of lore needs to be updated. Peter Parker was bit by a radioactive spider back in the 60s, but he hasn’t aged a ton since then, so logically, it follows that his Cold War-era roots really don’t apply to the character as we know him today. Some characters, however, are timeless or at least bear the fabrication of timelessness. Superman’s origin really has no necessarily set time or historical context attached to it: an infant child rocketed from a doomed planet hurtles to Earth, crashing in a field in rural Kansas. Maybe if, in some wayward future, America no longer needed farms or was transformed into a post-apocalyptic wasteland, the Man of Steel's tale would need tweaking. Yet, by and large, Kal-El’s formative backstory remains relatively unchanged.

Batman, in 1986, straddled that line. His origin, like Superman’s, has a timeless quality to it. The tragedy of a young man whose parents are murdered in an alleyway has not yet been marred by the march of decades; his single-minded pursuit to avenge them is not tampered by burgeoning social ideas, newfangled technological gizmos, or scientific know-how. There’s a deep philosophical notion underpinning the loss of the Waynes which has resonated with readers since the hero’s inception. The unfair caress of evil. The sudden touch of tragedy. The dedication to create good from mindless wrong.

Yet DC, in 1986, wished for a revamping. Their mega crossover event, Crisis on Infinite Earths, had torn the multiverse asunder, stitching together a new universe and a new earth for our heroes to reside. Titles like Superman and Wonder Woman were relaunched. Batman, though not relaunched, did receive an updated origin. Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli, the celebrated pair behind the lauded “Born Again” arc in Marvel's Daredevil series, were tapped to move Batman into the then-modern era. Though the Dark Knight’s origins have since been retold, Miller and Mazzuchelli’s four-issue story still remains one of the quintessential interpretations of the birth of Batman.

"Batman: Year One"

Writer: Frank Miller

Penciler: David Mazzucchelli

Inker: David Mazzucchelli

Colorist: Richmond Lewis

Letterer: Todd Klein

Issues: Batman #404-407

Publication Dates: February 1987-May 1987

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

It’s difficult overstating Frank Miller’s impact on the Dark Knight Detective, but "Year One" in particular is a unique animal. At the time "Year One" was published, Miller had already written and pencilled the critically acclaimed Dark Knight Returns limited series just a year before (a story I intended on discussing in the near future). Having envisioned a gritty depiction of a potential future for Batman, it made sense for the writer to tackle his past. Or, as writer-editor Dennis O’Neil stated, it made sense for Miller to give Batman an alpha (a beginning) after crafting his omega (an end). Miller had already impactfully shaped the critical and cultural awareness of Batman in his future, quasi-dystopian series, so why not probe further, deeper into that consciousness by burrowing further, deeper into the past?

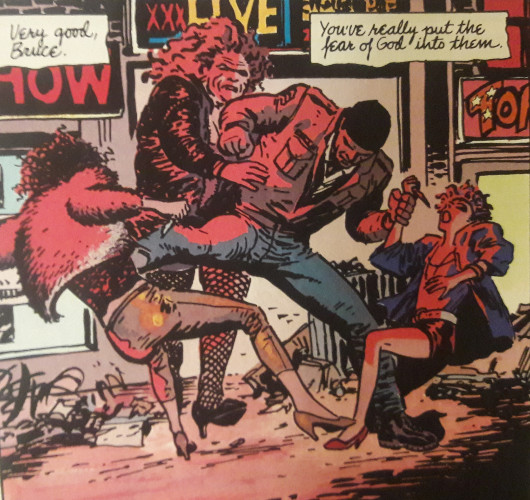

Dark Knight Returns, though grim and gritty, feels tethered to various other elements that make the story feel less like a purely street-level narrative. Sure, Batman swings across rooftops and wrestles thugs, but you also get a scene where robots that look like kids free the Joker or that climactic duel between Batman and a certain blue-and-crimson-clad Kryptonian "Year One" is even more grounded, featuring plenty of fist-to-face action and forgoing most “superhuman” aspects (aside from a couple subtle-ish references to Superman). We get a Batman just starting out; we witness his first few nights on the town as a costumed vigilante. Heck, in his first instance of vigilantism, Bruce doesn’t even don a costume, adding a fake scar to disguise his playboy visage and dressing like a bum. You want gritty Batman material? Watch Bruce prowl around the seedier districts of Gotham, laying the smackdown on a couple of thugs and getting stabbed in the leg for his troubles. No weapons, no armor, no sidekicks. Just a dude looking for trouble.

I would love to state factually that Miller brought his experiences with Daredevil to "Year One" but making such a claim is conjecture on my part. Several years after this story was published, Miller returned to Matt Murdock’s life to fashion Daredevil's own quasi-"Year One" story through the Man Without Fear limited series. The tales follow similar formulas: young men, lives altered by tragic circumstances, pursue justice as costumed characters. But even Man Without Fear is less a wholesale rewrite of Daredevil’s origin and more of a way to mesh Miller’s 80s run with DD’s early days as created by Stan Lee. Miller has no such bibliography to fall back on with "Year One." He simply grabs at the earliest Batman adventures–or, at an ever baser level, the core concept of Batman–and pulls them into 1987. He’s allowed a wealth of freedom in characterizing this updated Batman and his world, keeping the basic elements–the tragic origin, the bat motif–but running the story his own way. Miller doesn’t even spend much time on the origin itself: Thomas and Martha Wayne’s deaths are depicted fairly early on and fairly succinctly, letting Miller draw as much as he can from the event without elaborating on it.

And yet Miller maintains that nice “timelessness” quality I referenced earlier. Though clearly updated from Batman’s first appearance in 1939, "Year One" never feels specifically tailored to any time and place. The origin transcends time. Miller weaves in emotional relevance and resonance rather than dated references and details. Readers can easily grasp the reasons behind Bruce’s crusade, the shaken confidence of Jim Gordon, the miserable lifestyle of Selina Kyle, even the twisted corruption of Commissioner (not Jeph) Loeb. Mazzuchelli aids this effort by crafting a Gotham that's undoubtedly imbued with neon but feels dark and drab enough to balance out some of the poppier 80s excesses. This isn't Gary Frank's Earth One Gotham, which feels more akin to a teeming metropolitan city, or even Tim Sale's rendition from The Long Halloween, elongated skyscrapers enshrouded by shadows. Mazzuchelli splashes his streets and buildings with dirt. This Gotham isn't rising to success or even swarmed by darkness. It's a city...drab, a little lifeless, maybe on a head-on-collision with disaster if someone doesn't do something. It's nothing inherently special, but given its lack of uniqueness, transcends its bland demeanor to become something a little more real, solid.

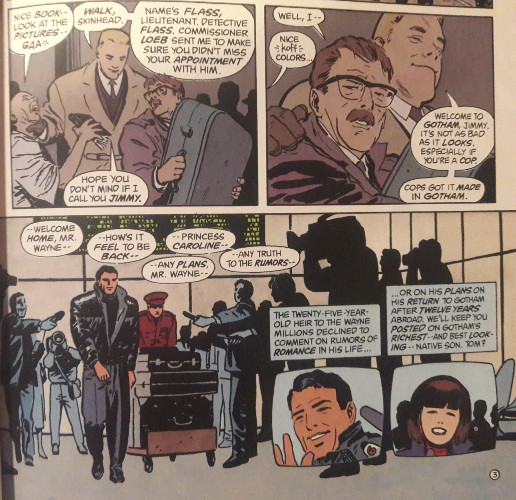

As the narrative unfolds, you’re asked, politely, to follow Jim Gordon’s story as closely as you do Bruce Wayne’s. Miller constructs fascinating parallels between the two men, right from the start. Opening pages see the men arrive in Gotham at practically the exact same time–Jim from his transfer over from Chicago, Bruce from his years abroad. Yet even here, differences resonate within their arrivals. Jim sees the city for the first time, not yet familiar with its dark corners. Bruce is returning to a city where he lost everything, from an emotional standpoint. He’s not numb to the grim underbelly of Gotham, but he’s more than familiar with the city’s recesses.

From here, narrative boxes bandy the thoughts of both characters as they strive to exist within this world. Jim sees that crime isn’t limited to thugs and pushers; the cops themselves add to the mounting filth, and the GCPD’s newest recruit finds himself embroiled in a world he could never agree with but can’t seem to abandon. Bruce watches the turmoil infesting his city and strives to combat it in his own, fists-first style. In an afterword illustrated by Mazzucchelli, Miller is quoted as saying that Bruce isn’t after revenge. Bruce wishes to reshape Gotham, transform it into a world where a young child wouldn’t have to watch his parents gunned down in an alley. Jim, too, wants a better Gotham, particularly for his wife and young son. Unaware as they are of each other’s activities and intentions for most of the book, each man is genuinely fighting for the same goal. Miller’s capably crafts this shared dynamic without ever verbalizing it.

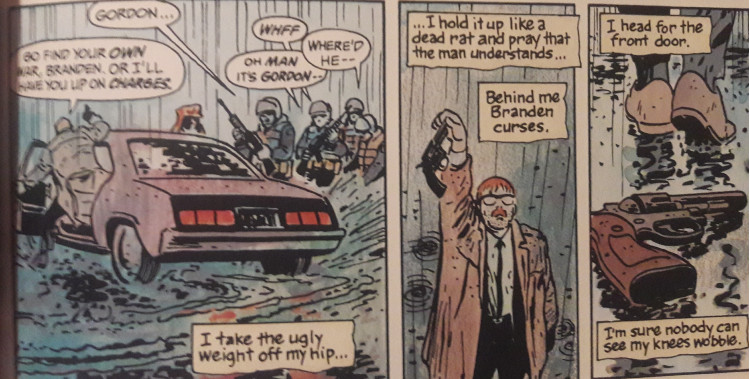

Desperation flows through both men, tempered by their inexperience in their current situations. Gordon is forced to grow into his role quickly, never losing his convictions but turning some corruption against itself. Beaten by a gang of officers, Gordon later turns on Flass, his partner, trouncing him and leaving him hogtied. He leaves, certain Flass gets the message: Gordon’s not to be trifled with any longer. You’ve shown me what it takes to be a cop in Gotham City, he mentally thanks Flass, driving off. Not afraid to get his hands a little grubby when he needs to, Gordon nevertheless represents a better ideal of law enforcement. He talks down a criminal instead of charging in, guns blazing. He reveals a recent indiscretion to his wife, not allowing himself to be bought via blackmail. The affair itself, though a chink in Gordon’s seemingly flawless armor, speaks to the officer’s character when he chooses the truth over fear.

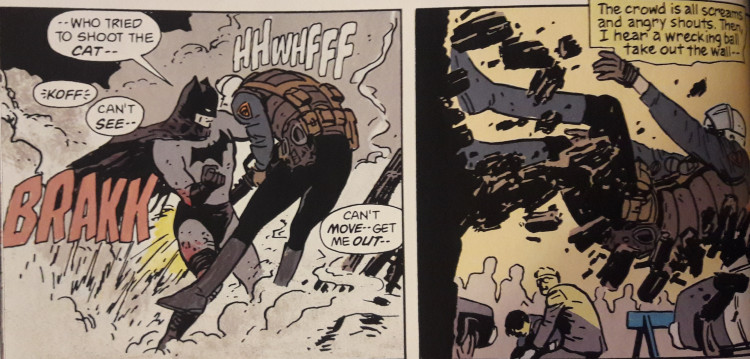

Bruce, driven as he is, discovers being a costumed vigilante is more difficult than it first appears, despite his years of training. His initial, costumeless foray into Gotham is a disaster, ending with him stabbed in the leg by a woman he tries rescuing. He nearly kills a criminal by accident during one of his first nights on patrol (another interesting parallel to Miller’s Man Without Fear, which sees Matt’s actions lead to the accidental death of an innocent his first time out). Bruce actually spends as much time out of costume as he does in it, indicating that this story really is just the start of his crusade. Much like how Geoff Johns would later mold the character in his and Franks' Earth One trilogy, Miller delivers a young, inexperienced vigilante, a far cry from the symbol he'd later become. One particularly action-packed sequence sees Bats come face-to-foot with a legion of cops, and though he avoids capture, his escape is narrow. He doesn't have all the gizmos, tricks, and plans-within-plans up his sleeves yet.

Even as he structures Batman’s first, fumbling forays into vigilantism, Miller inserts confident moments where the new Batman echoes the feared warrior he'll eventually become. The fight versus. the police, wonderfully detailed by Mazzucchelli, shows Bruce’s ingenuity and forethought; in a moment Christopher Nolan mirrored in Batman Begins, Bruce calls for a swarm of bats to cover his escape, a fearsome image that impacts both the police and people watching. An earlier scene watches Bruce blow a hole in the wall of the mayor’s mansion, interrupting a dinner for some of Gotham’s high-rollers (and, as indicated, some of the city’s more corrupt patrons). He rescues an infant near the end of the film in a scene reminiscent of his final confrontation with Two-Face in The Dark Knight; throwing himself at the child, Bruce risks his safety as he protects the boy from a perilous fall. The Batman may not yet be a legend, but Miller gives us reasons beyond his intentions to root for him as a character.

The Dark Knight Returns showed the allure of a darker, more mature Batman, a vigilante advanced in years and perhaps more brutal yet unwavering in his commitment to defend his city. "Year One" backpedals from Returns, offering the root reasons as to why Miller’s future Batman–and all incarnations of the hero in-between his beginning and aged state–may behave the way he does. Miller gives little space to Batman’s actual origin and years of training; his Batman begins fresh off the plane, already convinced of his path. It’s only when a bat smashes through his window that Bruce realizes the symbol he must construct in order to leave a lasting impression on his city. Likewise, as Jim Gordon moves through the filthy underbelly of Gotham City, he becomes convinced of the man he must become to fight crime. By story’s end, he’s not yet commissioner, just Captain Gordon for now. But it’s a step towards justice. Soon, a blazing signal will pierce the sky, Batman will drop in and out of Gordon’s sight surrounded by a dark mystique, clowns and penguins and cats will plague Gotham’s streets. But for the moment, as both men find their footing on a moral tightrope suspended above the city, they move in sync, wobbling and cautiously inching their way forward, convinced, if nothing else, that the rope will hold.