(Strand)om Stories: Daredevil: The Man Without Fear Review

Miller and Romita Jr.'s limited series wonderfully complements Miller's original Daredevil run, explaining some contrivances and offering depth to Daredevil's early days

—by Nathan on September 12, 2022—

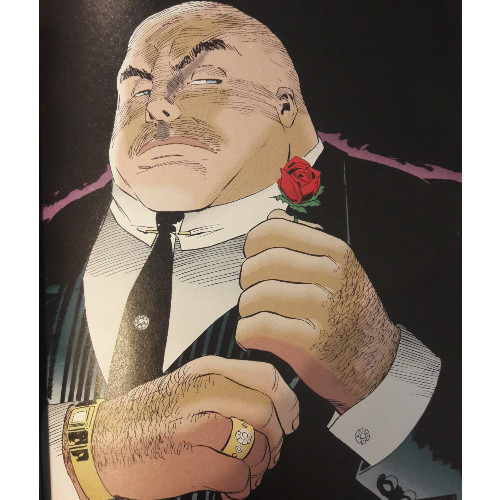

In the 80s, Frank Miller had a spectacular run on Daredevil, taking Matt Murdock’s alter ego and transforming him into a top-tier Marvel hero. Miller infused DD’s world with a crime noir style that blended in elements of mysticism and martial arts madness. He transformed the Kingpin into one of Daredevil’s greatest foes, instilled in Bullseye the madness and hatred the assassin continues employing against DD, and introduced and then killed Elektra, the tragic assassin who loved Matt Murdock.

Miller has, time and again, returned to his beloved vigilante (such as for the Daredevil: Love and War graphic novel and, most notably, the famous “Born Again” story arc), but when the early 90s rolled around, it had been a few years since he’d had Matt chuck a billy club. Yet Miller was brought back to the character, structuring a limited series alongside artist extraordinaire John Romita Jr., revisiting and revamping the origins and early days of the Man Without Fear.

Daredevil: The Man Without Fear

Writer: Frank Miller

Penciler: John Romita Jr.

Inker: Al Williamson

Colorist: Christie Scheele

Letterer: Joe Rosen

Issues: Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #1-5

Volume Publication Date: June 2010

Issue Publication Dates: October 1993-February 1994

Though not as well-known a story as, say, Spider-Man or Batman’s origins, Daredevil’s inception is still an engaging feat of comic book literature. In his first issue, creators Stan Lee and Bill Everett gave their hero a handicap—Matt’s blindness—injecting a unique form of relatability into the character and giving him an obstacle to overcome, as both Matt Murdock and Daredevil. Simultaneously, as Lee and Everett took away, they also gave: the accident which blinded Matt also granted him incredibly enhanced senses, which he used not only in his crime fighting guise but also liberally employed as Matt Murdock, lawyer by day.

Miller himself was no stranger to Matt’s origins; prior to taking on writing duties in the late 70s, Miller penciled several issues for writer Roger McKenzie, including a retelling of Matt’s origin. The issue is wondrously illustrated but is little more than an updated version of Lee and Everett’s original premise.

In the early 90s, Miller made his triumphant return to the red-horned character, penning a five-issue miniseries with an artist who had worked on many issues of Daredevil’s main series under writer Ann Nocenti. Man Without Fear is a radical departure from Lee and Everett’s original story, or even McKenkie’s story, in tone and character if not in concept. Miller does strikingly hits all the proper notes as initially conceived by Lee—a young man, blinded by radioactive waste, gains incredible sensory abilities and fights crime as a vigilante after the murder of his father. The story beats are all the same, but their presentation is a little bit different.

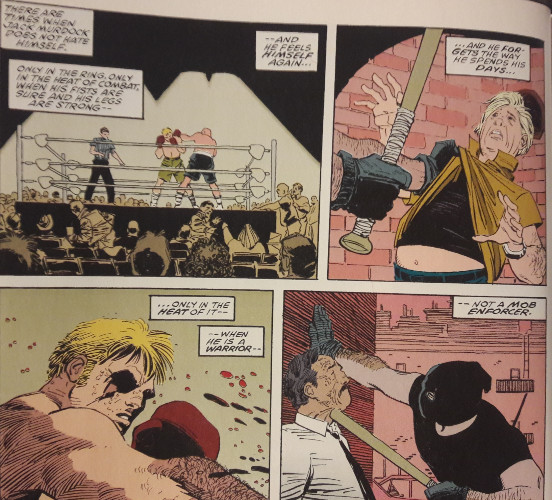

Miller pays homage as best he can, yet fashions the narrative through his own particular lens. Matt’s father, struggling boxer Battlin’ Jack Murdock, is presented as the same over-the-hill punching bag as Lee and McKenzie craft him, with the same heart for his son. Miller decides, however, to ratchet up the intensity. Jack isn’t just a has-been who’s thrown with in a mobster named the Fixer to, y’know, fix fights; he’s an enforcer, collecting protection money and threatening or injuring folks who can’t pay their dues. Miller gives Jack an edgier, darker demeanor, and I wondered while reading if I appreciated his approach. Lee and McKenzie never made Jack anything other than an old boxer, a father who cared for his son and kept fighting because it was the only life he knew. Miller’s version is a bit more sinister, a man desperate enough to side with the Fixer for a much-needed payout.

Thinking it through, I understand Miller’s change and realized I enjoyed it for practical reasons. In the original telling and retelling of DD’s origin, Jack’s side deals with the mob were simply based on his boxing career, paying him to win or throw matches. Miller plays with this too, but the leg-breaker angle gives Jack some more depth, a bit more dirt to tarnish his legacy or give Matt an additional emotional opponent. Prior stories had Jack push Matt to study, even after the accident which blinds the boy, simply because Jack didn’t want Matt becoming a has-been like him. In this limited series, Jack’s words carry a different ring to them, a hope that Matt won’t follow in Jack’s criminal footsteps and descend to his level of moral ugliness.

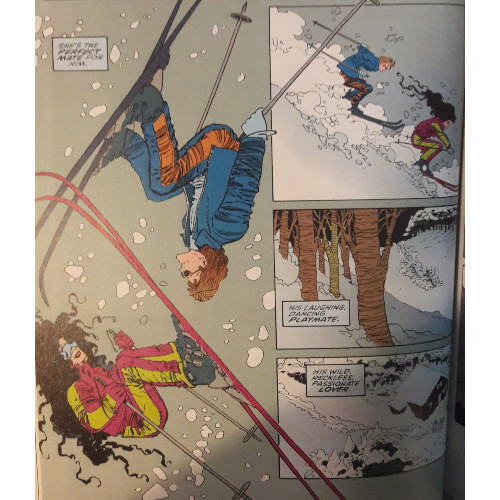

Elektra, too, receives a facelift, and her appearance in this series is a welcome addition to Miller’s mythos. I complained about her introduction in a previous post, wrestling with whether I could accept Miller’s take on her as Matt’s past girlfriend. He just lumps Elektra into an issue all of a sudden, yet we’re supposed to accept that she and Matt had a previously unknown history together. Miller works to correct that issue in this series, giving her a proper introduction as a free-spirited wunderkind, much like Matt. Their first interaction isn’t even a meeting, more of a sense as Matt realizes he’s come across someone who, like him, enjoys the freedom that can only come from gallivanting across rooftops. Much like Matt hides his abilities beneath a mountain of books and hours of study, so Elektra much oppress her freer, more savage side under the guise of her watchful father. Miller fleshes out their relationship as each finds in the other someone to understand, someone to escape with.

Miller, to me, never fully juggled Elektra’s arc well; he seemed to relish in the “assassin with a heart of gold” concept, yet always put too much emphasis on the “assassin” and not enough touches on Elektra’s human core. That changes in this series, as Miller makes Elektra more relatable that he had previously. A standout scene sees Elektra confront a bunch of thugs in an alleyway; shedding her fluffy mink overcoat, she engages in brutal fisticuffs, killing her opponents. Here, Miller balances the stifled, prim and proper princess with the vendetta-driven killer. Admittedly, you’re never directly told why Elektra chooses this lifestyle other than lashing out against the confines of her birth (in one somewhat literal interpretation, Matt must sneak past wrought iron fences and armed guards to try and visit her palatial homestead); hints are made, periodically, that her and Matt’s fates are intertwined with some greater war, but these are not explored.

It can be frustrating, certainly, when interesting pieces are teased without being fleshed out. Much of the series hinges on the reader’s familiarity with Lee and Everett’s origin, Miller’s Daredevil run, and to a lesser extent, the McKenzie/Miller retelling. Miller confines the actual accident which blinds Matt to a handful of panels, choosing instead of explore the aftermath and Matt’s recovery in a bit more depth. Miller skips over the death of Elektra’s father completely, removing what I thought was an intense, engaging sequence in his original run. Initially, I wondered why Miller would limit or remove certain integral story beats, but his reasoning quickly becomes clear. Man Without Fear is not so much a retelling as it is a reframing of Matt’s origin and formative years. “What if Frank Miller had written the origin of Daredevil?” seems to the basis upon which the series is founded.

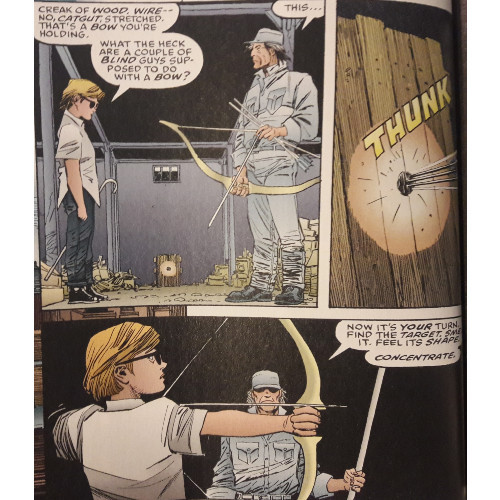

It’s Miller’s chance to incorporate his own mythology within the Daredevil history readers had already explored, and to a great extent, it works surprisingly well. Miller makes the Matt/Elektra love story a central theme, fleshing it out over an issue-and-a-half. As I indicated above, this improves Elektra’s character greatly, putting her at an earlier part of Matt’s burgeoning history rather than throwing her in the middle and claiming she was an important piece the entire time. Likewise, Miller incorporates Daredevil’s mentor Stick, an old martial arts master who sees Matt as a member of an oncoming conflict between his group the Chaste and the villainous Hand, whom Elektra served as an assassin (and who once brainwashed Wolverine in another little Romita Jr.-depicted drama). Little of that mystical combat influences this series, but Miller inserts it as bedrock into Matt’s origin. Stick isn’t just an old guy who wants to draw Matt into a convoluted war; he’s a sensei, training Matt in his senses and helping him overcome his weaknesses. Lee and Everett tried their best to fashion a practical understanding of Matt’s abilities and training, that hours in a gym kept him fit and allowed him to hone his supernatural senses. Yet by having Stick enter the picture from the beginning and taking on Matt like some kind of sightless Robin, Miller enhances DD’s credibility as an athlete and fighter. In Stick, Matt finds a kindred spirit, much like Elektra, but Stick offers Matt comfort and grace as the future Daredevil works his way through the first steps of his vigilante career. Heck, Miller doesn’t even push the whole superhero/ninja warrior aspect on Matt at first, letting the boy take his first, fragile, uncertain steps into his new world—a world he cannot see but must learn to traverse.

When initially reading Miller’s run, I was never wholly comfortable with the mystical/martial arts aspects he included. Miller’s version of Daredevil and Hell’s Kitchen is largely grounded, based in crime noir and drowning in grim tales of bounty hunters, crimelords, and vengeful assassins. The interplay of his crime-centric narratives often clashed with the Stick/Elektra/Hand/Chaste elements. Yes, it added a wildly new and original angle to the Daredevil mythos, but it also muddied the waters by giving Matt some kind of “Chosen One” element that never fit with his character. Wisely, Miller avoids pushing those aspects in this retelling. He weaves in aspects of his own stories, yet saves some of the stranger pieces. I felt like Miller was almost preparing his audience for the run he’d already written, teasing his readers with a “prologue” of sorts, promising them greater things to come should they choose to dive into his stories from the 80s.

Amazingly, then, this means Man Without Fear is wonderfully accessible to readers already familiar with or blissfully unaware of Miller’s take on Daredevil. For the initiated, the limited series is a fantastic return to Miller’s world, hinging on the narrative beats and characters I’ve outlined above, a love letter to his acclaimed work. For the uninitiated, the series works as an introduction, combining classic Daredevil tropes with Miller’s wholly different and unique take on the character. Nicely, the series truly feels like an appetizer before the main course—granted, a few decades of history exist between these “Year One”-style tales and Miller’s own run, but it would be rather easy to jump from this series to Miller’s 80s narratives. Or vice versa. The choice is yours, and I can hardly think of a reason to suggest one or the other.

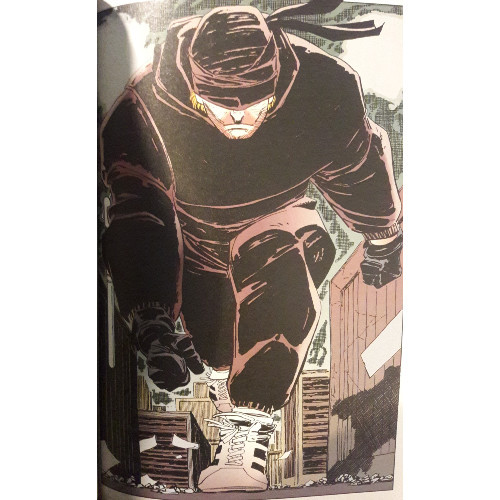

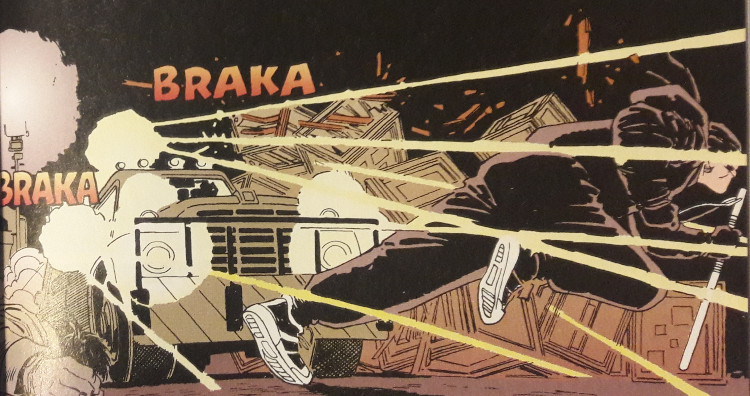

Romita Jr. is at top form in this series, crafting fluid action sequences that showcase a darker take on Daredevil than previously suggested from this era. Skipping over the yellow costume entirely, Romita Jr. crafts a grim “pre-Daredevil” outfit, a black suit the Netflix series’ first season adopted. Action and violence are prolific, yet frantic, as Romita Jr. captures Matt’s motion fantastically. The artist has the talent to convey our hero’s cat-like instincts, his fighting prowess, and his acrobatic motion perfectly. His Kingpin conveys a similar sense of overpowering menace as artists Bill Sienkiewicz, Alex Maleev, Joe Quesada, or even JR. Jr.’s father, John Romita, gave the sizable crimelord. Romita Jr.’s style, as I’ve most likely commented previously, is instantly recognizable, and his blend of realistic-looking backgrounds and expressive, quasi-exaggerated characters has cemented his ability as an artistic master of the genre. You know what you’re getting when you read a Romita Jr.-penciled piece, and most times, it’s awesome.

Miller and Romita Jr. create an impressive piece of Daredevil literature with this series—they don’t necessarily rewrite Horn-Head’s history, but they do lovingly jostle and reframe it through a more modern lens, somewhat akin to Miller's earlier work on "Batman: Year One." The story isn’t necessary, by any means; I’m not sure how many fans were clamoring for Miller to insert more of his 80s mythology deeper into Daredevil’s early days. But the experiment complements the original stories while adding to Miller’s legacy. Miller and Romita Jr. politely play with the past, proactively leaving foundational elements untouched while laying some good bedrock for Miller’s run. These changes, fantastically, make Miller’s run more readable, offering much-needed context for some of his narrative decisions, such as Elektra’s background and the start of her relationship with Matt Murdock. Admittedly, as a standalone series, it’s a little difficult to enjoy if you either haven’t read Miller’s run or don’t intend on reading his 80s narratives. This one really is for the fans who want a more “complete” collection of Miller’s work. As a bookend to Miller’s Daredevil run, this certainly feels enjoyable enough to warrant a read from anyone interested in complementing their understanding of Frank’s further fictions.