(Strand)om Stories: Wolverine: Enemy of the State Review

An engaging concept makes for an exhilerating story, even if it is somewhat hampered by a few narrative choices

—by Nathan on January 9, 2022—

We’ve seen, time and again, how writers and artists strive to add complexity and nuance to the berserker hero known as Wolverine. During his several decades of published history (and many more decades of in-universe history), Marvel’s mightiest mutant has been a loner, a hunter, a lab rat, an assassin, and a superhero. He’s donned many costumes, fought many foes, and relied on his instincts, healing factor, and the help of his X-Men family to carry him through the years.

Writers always seem to love tangling with Wolverine, coming up with kooky concepts that push our mutant friend to his limits. If it isn’t Barry Windsor-Smith subjecting the poor sap to torturous experiments, it’s Mark Millar forcing him to murder his friends and spending decades wallowing in misery. But the praise-worthy Old Man Logan wasn’t the first adamantium-laced shot Millar took at our Canadian crony; shortly before the Scottish savant painted his version of a grim Marvel future, he toyed with Wolvie in the mainstream Marvel Universe, reminding all of us why Wolverine is the worst at what he doesn’t do pretty…

...or something like that.

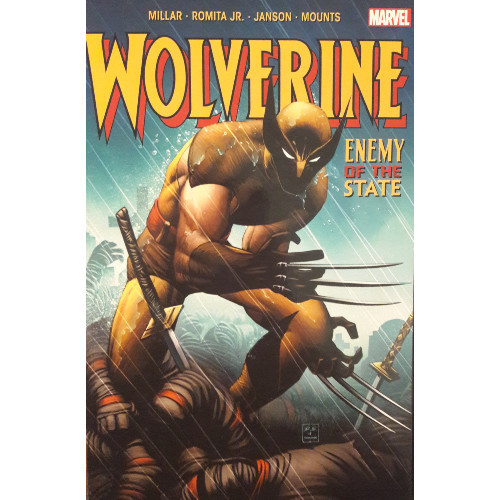

Wolverine: Enemy of the State

Writer: Mark Millar

Pencilers: John Romita Jr., Kaare Andrews

Issues Collected: Wolverine #20-32

Volume Publication Date: April 2020 (latest edition)

Issue Publication Dates: December 2004-November 2005

From my limited experience from reading Wolverine’s adventures, I’ve started concluding that the best James “Logan” Howlett stories are the ones which pick apart his core characteristic: killer with a heart of gold...erm, not gold...some other metal...I dunno...steel?

Or is that the other guy?

Introduced as a Hulk foe, Wolverine was quickly folded into Chris Claremont's uncanny team of X-Men. Starting off as a short-statured, short-tempered fuzzball, Wolverine stared down Cyclops, fawned over Jean Grey, and generally made himself somewhat unlikeable. Claremont soon steered the killer Canadian a different direction, unfolding the humanity hidden in the beast’s heart. He became a staunch hero, a valued team member, and a father figure to more than one younger hero. Beneath the grim exterior lay a noble warrior, a man who’s life was constructed upon principles he strove to follow.

So these “best stories” I mentioned, they try to rip that apart, take that key characteristic and manipulate it. Wind the key in a different direction and see how Logan maneuvers. Windsor-Smith’s “Weapon X” arc literally tore Logan apart, coating the character in his infamous adamantium and exploring the grim backstory behind his famous claws. Paul Jenkins’ Wolverine: Origin delved deep into the past, examining the young, frail boy who would one day grow up to become the Man of Adamantium. Even Christopher Priest's "Spider-Man vs. Wolverine" one-shot pitted the killer against his Web-Headed playmate, pulling at the mutant hero's heartstrings as tragedy struck while highlighting the obvious differences and much more subtle similarities between the two men.

“What if?” is a fascinating question to drive Wolverine stories, especially when they become core character arcs in the main Marvel Universe. “What if the rough-and-tumble warrior was born a sickly child? How does that aid his development?” “What if the mutant with the impressive healing factor found that his healing factor was broken?” “What if the noble warrior was subjected to torture and horrific experiments?” How does Wolverine react? Who does he become?

Millar has his Logan take a literal jab at that notion in "Enemy of the State." As I already pointed out, Millar would later twist Logan’s world, stripping him of his original family and seeing what Wolverine would become without his support system and claws. Here, Millar moves in a different direction. He doesn’t take Wolverine’s friends or family, he doesn’t make Wolverine swear off using the claws. Millar’s “lack” is as philosophical as it is physical. He takes Wolverine’s mind.

Kidnapped by the Hand, Wolverine is brainwashed by the fanatical terrorist group and set upon an unsuspecting world. The idea is, at its core, a fascinating avenue to explore. Wolverine has, as we’ve seen, already been subject to mental manipulation. But the Hand’s attempts are different from Weapon X’s--where the Canadian cabal was attempting to create a weapon, the fanatical fascists warp that weapon to their command. They did so before with Elektra. Why not with the ultimate weapon?

While reading, I asked myself why someone hadn’t conceived of a similar plot before (or, if they had, why they hadn’t written it). The answer, once I finished the book, became slightly clearer: “Wolverine becomes brainwashed killer” suddenly opens up the floodgates for massive story potential, and if this were a tale told in an alternate universe, I could easily see it becoming a “Deadpool vs. The Marvel Universe” type of tale, wherein Wolverine murders everyone within sight. Such storytelling could become repetitive, if done improperly. Millar runs a very thin line throughout the entire story, maintaining a tentative balance between falling into mediocrity or overindulgence.

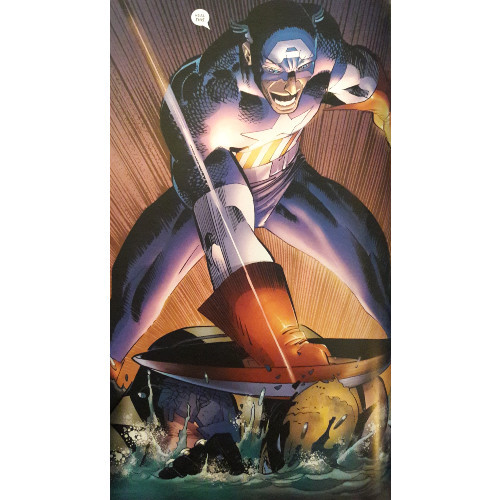

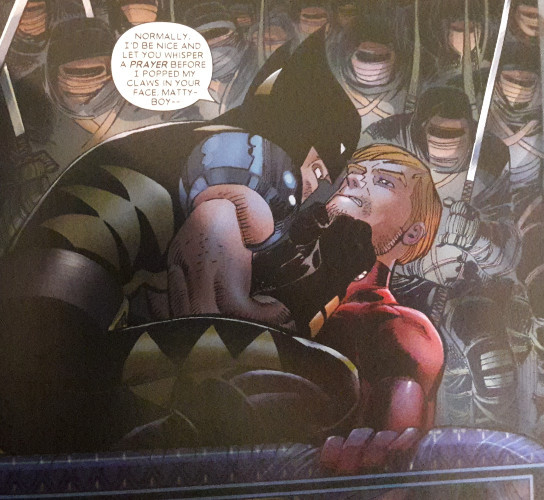

By “mediocrity,” I mean a tale which could have easily grown dull: Wolverine attacks several heroes in this story (the Fantastic Four, Daredevil, the X-Men), yet each of the scenes feels unique. Wolverine breaks into the Baxter Building, setting up a James Bond-style sequence where stealth blends with action. He confronts Daredevil in his own apartment, bringing to mind Frank Miller’s run on the character and the long-running enmity between Matt Murdock and the Hand. The X-Men sequence is bombastic, involving Wolverine crashing the X-Men’s Blackbird jet through the house, threatening Rachel Summers, and stabbing Northstar during a frantic chase through the woods. Each of these scenes allows Millar and artist John Romita Jr. ample opportunity to play with Wolverine’s character. His hunter/tracker skills carry him deep into the Baxter Building and allow him to sneak up on Daredevil, DD’s heightened senses be darned; his fierce, animalistic tendencies come into play during the X-Men fight, a scene awash with emotion as Wolverine’s internal monologue runs rampant, his more heroic side straining against the brutal brainwashing.

When I said “overindulgence,” I meant to convey a sense of violent gluttony, of Millar leaning heavily into his personal penchant for brutally murdering scores of people. Old Man Logan showered readers with buckets of blood, and though one particularly brutal scene was used for dramatic emphasis and narrative propulsion (the moment breaks Wolverine, setting up the series’ main internal conflict), a later scene felt to me more unnecessary. Millar simply allowed Logan to give into his wild side and wreck bloody vengeance. Here, Millar and Romita Jr. hold back...a little. Demonic ninjas are torn apart and dusted, people are stabbed, limbs are severed...yet none of it feels excruciatingly over-the-top. Romita Jr’s art has always fallen on the tad more exaggerated end of the spectrum, so even scenes where arms are hacked off or people are gored more tamely (“gored more tamely”?) than, say, Steve McNiven’s depictions in Old Man Logan. You can (for whatever reason) let your mind soak in his violence and take those moments to their more logical, realistic conclusions. But why?

But what does that mean from a narrative standpoint? If you, intentionally, hold back your brainwashed murder machine, or not let him kill characters who are off-limits or too important to the mythos at large, doesn’t that weaken the story? Wolverine racks up a body count, but most of his kills happen to low-level criminals or guys we’d probably never see again anyway. The one heroic character he nastily does in later returns, brainwashed himself. Millar skirts around by setting Wolverine up, not as the Hand’s go-to killer-for-hire, but as an unstoppable agent working on other plans. If he’s gotta kill people along the way, so be it.

It works, partially. The idea doesn’t hurt the “brainwashed Wolverine” plot, which Millar strengthens with a running, dual internal monologue as Wolvie’s more heroic nature struggles to fend off the brainwashing. And as I said, each action sequence is played out very well, bolstered by Romita Jr. and never becoming stale. Yet part way through, Millar turns the narrative on its head, and though this keeps the story beats fresh (Wolverine, I’ll spoil, may end up killing for someone else), the theme doesn’t change: Wolverine still kills, just for another “employer.” Millar, certainly, isn’t making any kind of comment about Wolverine’s more murderous nature, basically equivocating the whole “is a killer killing killers better than a killer killing anyone else?” concept. Not much depth to be found there. The thematic elements are, honestly, stronger when Wolvie’s internal struggle rages. The dual voices, fighting to gain control, gets at the mindless murderer vs. knife-handed hero concept. When Wolverine slinks away from that notion, he’s left to redeem himself, certainly, but Millar doesn’t make this super clear, nor does he inject enough subtle detail for you to think down that philosophical line. He seems more interested in switching things up, and again, it works to keep the story beats moving at a steady pace. But it leaves little to consider once the dust (from the obliterated bodies of several Hand ninjas) has settled.

Included in the volume I purchased is the Wolverine issue immediately following the end of "Enemy of the State." It has nothing to do with the story arc whatsoever but stands out as a jewel. Set in a Nazi concentration camp (remember, Logan’s an old man, even if he isn’t quite an Old Man), Millar and Kaare Andrews’ short story focuses on a brand new camp warden, sent to replace the old one who recently died of suicide. Millar and Andrews set up a grim horror-esque story that sees the new warden try to do whatever he can to eliminate one bothersome prisoner who seemingly won’t die. Bet you know where this is going. Andrews encapsulates his grim setting, depicting a Wolverine who never needs to pop his claws to get a reaction. Use of shading keeps Logan more shadowed than fully illustrated, leaving the reader largely unaware of his emotions but still feeling through his overpowering, sinister silhouette. The issue is a breather from the fast-paced arc you’ve just finished, a wonderfully engaging tale with few words yet massive potential.

“Brainwashed Wolverine” makes for an engaging character study for Logan, especially as Millar wrenches the character’s core around like he’s trying to rip Wolverine’s heart out. Millar and Romita Jr., largely, get to the crux of the character’s emotions, placing him in a situation where he’s no longer in control of himself and playing out the ramifications beautifully. Yet the concept is muddied once Wolverine asserts dominance over himself, sort of creating the same deflating ending that Millar gave Old Man Logan. If Wolverine’s cutting up the bad guys instead of the good guys, that’s a good thing, right? Not necessarily...or, if the argument can be made for why such actions are justifiable, Millar prefers his story look visceral and violent instead of defending his response. Maybe you just won’t see him shrugging through the crimson haze.