(Strand)om Stories: X-Men Epic Collection: The Sentinels Live Review

A few awkward revelations cannot throw off the exceptional narratives, artistry, and character growth contained in this bombastic volume

—by Nathan on November 22, 2021—

Professor X is dead. Long live…

Nobody, really.

A shocking turn of events near the end of the X-Men's second Epic Collection saw the beloved Professor X die before his students’ very eyes. The brilliant professor gave his life to save his pupils; shortly thereafter, his most hated foe, Magneto, seemed to perish in a disaster as well.

Thus is the shape of the world the X-Men enter as we turn the first few pages of this third Epic Collection: no Professor X to guide our heroes through the horrors of an insensitive world, but no Magneto to compound those terrors with his firebrand rhetoric and disastrous deeds. The team has, seemingly, been altered forever. How can writers latch onto those alterations and use them for their benefit?

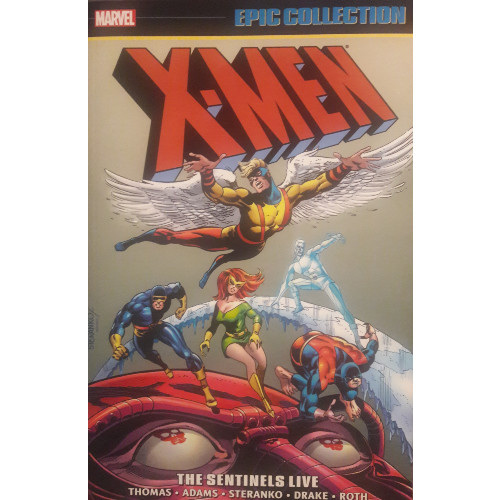

X-Men Epic Collection: The Sentinels Live

Writers: Roy Thomas, Arnold Drake, Gary Friedrich, Dennis O’Neil, Linda Fite, Jerry Siegel

Pencilers: Neal Adams, Jim Steranko, Werner Roth, Don Heck, George Tuska, Barry Windsor-Smith, Sal Buscema

Issues Collected: X-Men #46-66, Ka-Zar #2-3 (back-up strips), Marvel Tales #30

Volume Publication Date: April 2021 (latest printing)

Issue Publication Dates: July 1968-March 1970, December 1970, March 1971-April 1971

I guarantee, pretty much the only initial reason I bought/read the first two X-Men Epic Collections was to get to this one.

I’ve discussed, sporadically, how my interest in the X-Men, for both the original Stan Lee/Jack Kirby/Roy Thomas material and Chris Claremont’s later run, peaked in high school. As much as I thoroughly enjoyed browsing Marvel Masterworks containing early Claremont narratives such as the “Dark Phoenix Saga,” I was utterly bowled over by the stories I read during Roy Thomas’ second run on the book, primarily for one reason: the artwork of Neal Adams.

Adams, back then and even now, conveyed a sense of depth and detail fellow artists such as Werner Roth, Don Heck, and George Tuska were unable to probe. I could not tell you which artist was which, even after reading this volume recently, if you showed me a random panel from a random comic contained therein. But Neal Adams? With his exquisitely detailed line work, frighteningly realistic imagery, and wonderful panel construction, he breaks the rules prior artists have followed on the book and absolutely makes the X-Men his own (look no further than a gorgeous sequence where Ka-Zar confronts enemy the Piper, a series of panels devoid entirely of words). His work stands out to me just as strongly now as it did back in high school, and I still found myself constantly impressed by how “modern” his art appears to be. This guy was doing stuff in the early 70s that you never saw in other books at the time. I could even swear that fellow X-Men artist Don Heck adapts his own style to ape Adams’ for a fill-in issue late in the volume.

Not to be ignored, however, is the work of Jim Steranko. I’m convinced that I must have missed a Marvel Masterworks volume when reading Thomas’ work, because for the life of me, I could not recall the few issues Steranko illustrates for this volume. Steranko’s was a name I’d heard about briefly, largely due to his historical contributions to the S.H.I.E.L.D. mythology over in Strange Tales (no, not the Cloak and Dagger/Dr. Strange series of the same name). Largely unfamiliar with his work, I was awestruck with his artistic talents, his work surpassing that of contemporaries Don Heck and George Tuska. Steranko’s linework, crisp and detailed, isn’t quite on the same level as Adams’, but he’s so diligent with crafting his own style that the few issues he pencils wonderfully stand out. Other artists included in this and other X-Men Epic Collections try too darn hard to style themselves after Jack Kirby, working to keep a similar tone. Even Barry Windsor-Smith, who contributes to a single issue, conforms to the masters of yesteryear, his style a far cry from the gorgeously detailed displays he’d use in stories like "Weapon X", Uncanny X-Men #186, and the “Stark Wars” epilogue (Iron Man #232). Steranko and Adams both buck that trend, forsaking well-trodden paths for their own direction. The book soars as a result.

Prior to Roy Thomas’ return, Arnold Drake and Gray Friedrich develop several adventures for our stalwart group. With Professor X dead, the writers seem almost at a loss...what to do with a leaderless X-Men? Amusingly, they choose to temporarily disband the team and send the characters on their separate ways. This allows the writing team to tackle character dynamics in ways previously unheard of as the characters no longer need to rely on each other. Iceman and the Beast pal around, tackling a villainous warlock as he tries mind-controlling a theater audience; Cyclops and Marvel Girl, pretending to be an “item,” pair up for an extended adventure which brings the team finally back together.

But these new dynamics don’t last long enough to become a well-entrenched concept or focus for engaging character growth. It feels like Drake and Friedrich simply ran with the idea of the X-Men disbanding because, naturally, the death of Professor X would certainly be enough impetus to break the team apart. They played the hand Thomas dealt them. Thus, at first chance, they brought the team together again, meaning an extended X-Men hiatus was never necessarily in the cards. Still, the idea of our merry mutants becoming a handful of distinct groups or pairs for a longer period of time would have been highly engaging. A buddy-buddy book with Iceman and Beast? Sounds great!

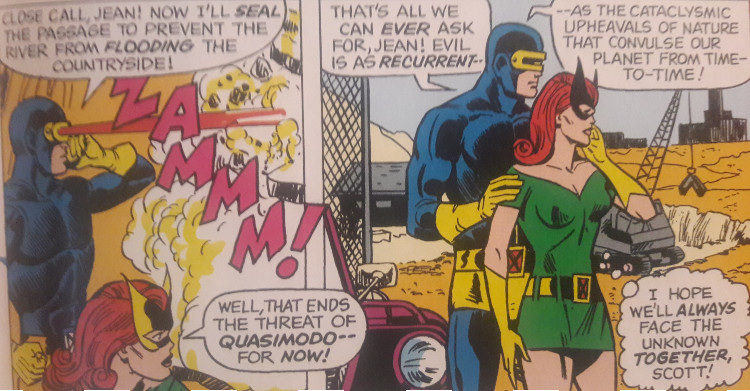

Professor X’s death, fortunately, offers Scott some much-needed character development. Always the second-in-command simply by default (and, of course, the X-Men’s field leader because Xavier could rarely join his team on missions in any significant manner), Scott now embraces his leadership role and grows positively as a result, taking charge out of necessity, not just because he was Xavier’s right-hand guy. He comes across as more confident and capable, stronger as a result of his mounting responsibilities.

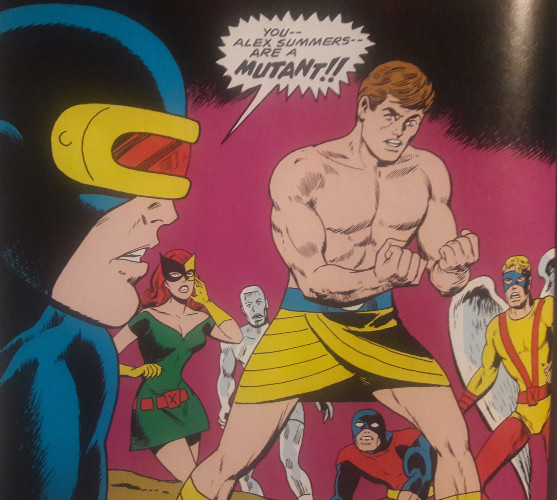

Through their issues, Drake and Friedrich never seem quite too sure what to do beyond their overarching “Professor X is gone” story idea. They toy with a variety of plots that combine originality with history--Magneto seemingly returns, announcing that young Lorna Dane is his daughter and heir; the aforementioned villainous warlock is an adaptation of a character Thomas used in a previous story; readers are introduced to Scott’s brother, Alex, who also happens to be a mutant and later takes the name of Havok. They throw ideas and events at the wall at a helter-skelter pace; gone are the more elaborate arcs, such as the Factor Three plotline Thomas developed. Stories are kept to smaller issues, with few meandering subplots to unify them.

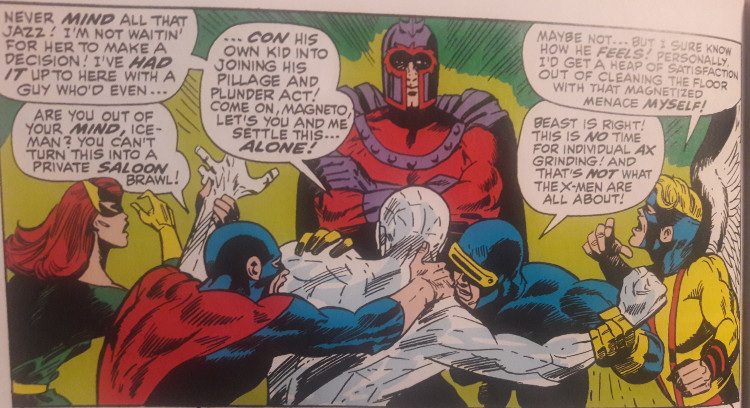

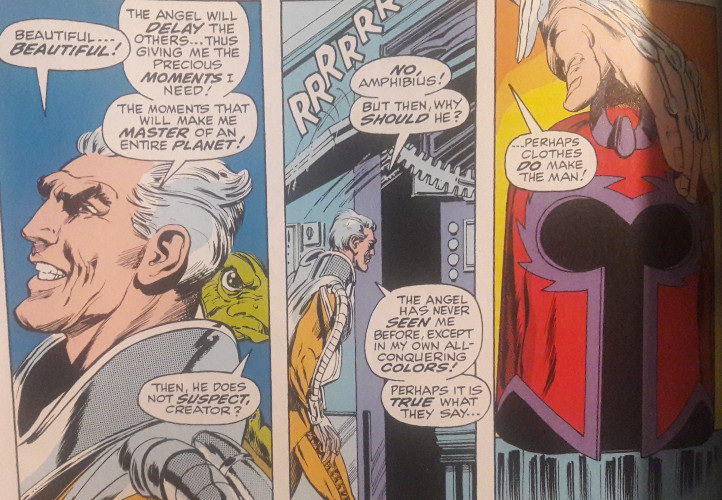

When Thomas returns, he strikes with a vengeance, surprisingly upending much of the work done by Drake and Friedrich. Mangeto’s return is literally destroyed when the Master of Magnetism is revealed to be a robot, Iceman’s attraction to Lorna (who starts going by Polaris) is threatened by Havok’s presence. Thomas even overturns his own shocking plot twists--the supposed deaths of Magneto and Professor X--by reestablishing the status quo late in the game. Both men return, and though their reappearances are welcome, only Magneto’s “resurrection” feels justified. With Neal Adams, Thomas brings the villain back deadlier than ever, conning the X-Men in a highly entertaining story that features Ka-Zar and the Savage Land, in a nice nod to some of Lee and Kirby’s original stories. The reveal, though somewhat obvious, is nevertheless set up decently well so that the twist, whether or not the reader is surprised, is highly appreciated. Magneto is back, boys and girls, and he’s here to stay.

The same cleverness cannot be said for Professor X’s rise from the grave. Part of this occurs because the matter is consigned to a single issue...one not even written by Thomas. Until that moment, Thomas had been working on highly engaging arcs that didn’t necessarily build upon each other but nevertheless work remarkably well as standalone epics. Yet at the end of his second larger arc, Thomas momentarily passes the writing reins to the late Dennis O’Neil, who brings Xavier back. O’Neil’s explanation for Xavier’s return--that the professor had momentarily swapped places with shape-shifting X-Men foe the Changeling so he could secretly focus on an oncoming alien invasion--feels sudden. The Changeling piece is certainly clever, but otherwise, Xavier’s return feels overly dramatic, sudden, and not at all fleshed out. Wonky writing and coincidental timeliness turn what should be an exceptionally important plot point into a mundane story without the gripping emotional impact it needed. The revelation lacks the build-up and importance of Magneto’s return.

Sorry, Chuck. I’m not buyin’ it.

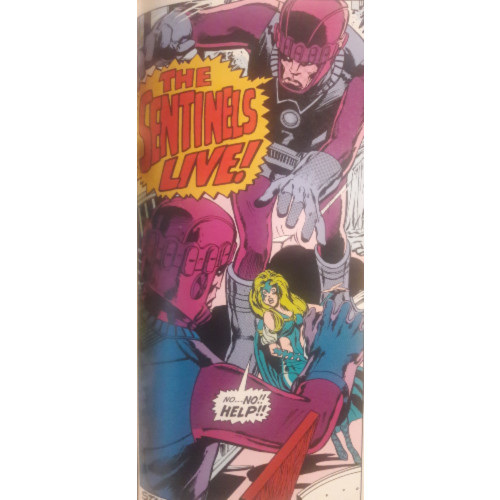

I’ve ragged on this volume a bit, I know, which is somewhat unfortunately because I mentioned I was so dang excited for it. Praise Xavier, then, that the arcs I was primarily interested in are still as good as I remember them being. Together, Thomas and Adams construct three story arcs--which see the return of the Sentinels, the debut of Sauron, and the return of Magneto--all of which benefit greatly from Thomas’ writing prowess and Adams’ illustrations. Thomas is supremely focused here, writing arcs which feed into each other and share dynamic characters and themes. The Sentinel arc represents some of Marvel’s strongest commentary on human/mutant relations at the time, a genuinely gripping story with bonkers plot twists and a thoroughly satisfying ending. Sauron, a vampiric mutant transformed into a pterodactyl, is one of Thomas’ most original creations (in all but name) and a bizarre yet thrilling villain. And Magneto’s return, as I’ve already discussed, is a triumph of storytelling. Even knowing what was going to happen, I read the panels with elation as Thomas and Adams built up the tension to the final reveal. For eight issues, X-Men becomes the absolute premiere superhero comic it’s always wanted to be...an achievement it wouldn't reach again until Claremont boarded the mutant train.

Is this collection disjointed? Absolutely. But does it nevertheless represent the height of mutant superherodom circa 1970? You betcha. Characters feel more real here than they have in the previous two volumes, and the art--particularly that of Steranko and Adams--represents the high-water mark of the book, a feat which not even the legendary Jack Kirby could reach, in this author’s humble opinion. Yes, a lot of it is wonky as plot points overturn themselves and engaging concepts fizzle at moments, but nevertheless, when this mag is good, it gets really good.