(Strand)om Stories: X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Review

Based on a somewhat ridiculous premise, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's marvelous mutants nevertheless provide unique characterization and engaging conflicts

—by Nathan on June 14, 2021—

I’ve discussed at length Chris Claremont’s impact on the X-Men, specifically during the first several years of his run on Uncanny X-Men. Feel free to peruse the following posts for more careful examinations of recent omnibuses collecting several of his stories:

Uncanny X-Men Omnibus (vol. 1)

Uncanny X-Men Omnibus (vol. 2)

Uncanny X-Men Omnibus (vol. 3)

Uncanny X-Men Omnibus (vol. 4)

As I’ve elaborated on previously, I first discovered Claremont’s work back in high school, reading a small piece of his run (up through the “Dark Phoenix Saga”) through Marvel Masterworks volumes I borrowed from the library. Around the same time, I also dipped into earlier X-Men sagas, spanning the runs of Stan Lee and Roy Thomas. Thomas’ time on X-Men, particularly his work alongside Neal Adams, wowed me.

As I’ve run out of Claremont-focused omnibuses to comment on (for the time being), I’d like to examine a few of the Epic Collections which have gathered those earlier eras of mutant superheroics. These volumes take us back to the 60s, to the X-Men’s roots, as we explore the inaugural issues of the series.

X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom

Writers: Stan Lee, Roy Thomas

Pencilers: Jack Kirby, Werner Roth, Alex Toth

Issues Collected: X-Men #1-23

Volume Publication Date: January 2015

Issue Publication Dates: September 1963-August 1966

Part of the fun of reading these early issues recently has been comparing and contrasting them to the Claremont-penned stories, seeing how far the series evolved from the time Lee introduced the world to his mutants to when Claremont started writing. From the get-go, I realized that I was encountering a series that felt more surreal than other 60s-era Marvel comics I’d been introduced to. Not that series such as Fantastic Four, Incredible Hulk, or Amazing Spider-Man weren’t filled with insane adventures and kooky characters, but those series feel far more grounded than X-Men.

The Fantastic Four were a group of adventurers who tried beating the Soviets to space and wound up with incredible powers, uniting as a team/family as they learned to cope with the reality of their new situation. The Hulk was mild-mannered scientist Bruce Banner, who was irradiated in a freak accident and became a green-skinned, rampaging personification of rage. Spider-Man was a teenager who gained powers by a spider bite and very quickly learned he needed to use those abilities in a selfless, heroic manner following the death of his uncle. Humanity strikes at the core of each of these origins and concepts. Our characters, through their very origins, become sympathetic to readers.

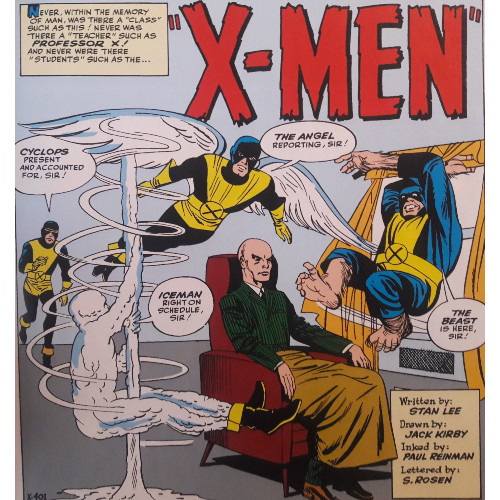

Not so the X-Men. Stan Lee admittedly stated he didn’t want to think up new origins for this team of heroes; thus, our five original X-Men--Cyclops, Angel, Marvel Girl, the Beast, and Iceman--their leader Professor X, their arch-enemy Magneto, and several other mutant heroes and villains are simply born with their abilities, which usually come to fruition during adolescence. This lack of emotional storytelling allows Lee and Kirby to jump straight into the action, but it also sets up a bizarre and sometimes unfortunate precedent for the X-Men’s world: spontaneity.

With Spider-Man, you the reader are methodically introduced to Peter Parker, his world, and his supporting cast even before he gets his incredible abilities. You get to understand the character and how he becomes a hero. As Amazing Spider-Man progresses, you become more aware of the world Peter inhabits, the characters he interacts with, the villains he faces. Super bad guys receive abilities, develop, find their niches as bank robbers and terrorists and revenge-fueled criminal masterminds. Spidey's stories feel, to a certain extent, planned out. Many, many of the elements Lee and penciler Steve Ditko introduced during their time on the book, including characters and locations, remain true to the Spider-Man mythos nearly sixty years later.

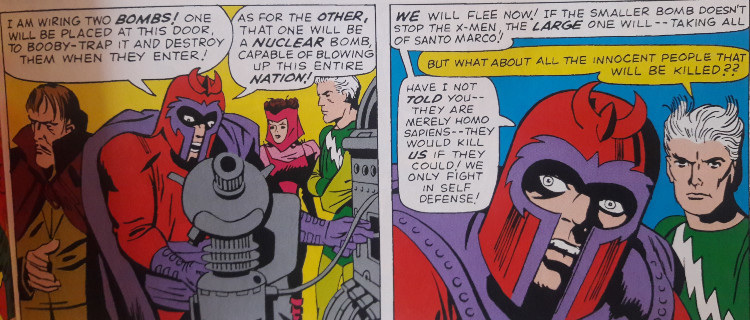

X-Men, on the other hand, lacks that sense of structure. Boom, from page one, you’re thrust into a realm where beings with incredible powers can pop up at a whim. Mutants, suddenly, are crawling out of the woodwork. And, strangely, they all seem bizarrely aware of the social stigma associated with being a mutant. Within the first few pages of the inaugural issue, Professor Xavier has explained the series’ basic premise--the X-Men have been formed to combat villainous mutant threats in a world that despises and persecutes mutants. Magneto, introduced at around the same time, threatens a world he wishes to rule, convinced of his own genetic superiority. Lee and Kirby are, mostly, able to cement the conflicting Xavier/Magneto schools of thought decently--both philosophies are rather simplistically stated but are also easily understood. Xavier wishes to defend; Magneto desires to rule.

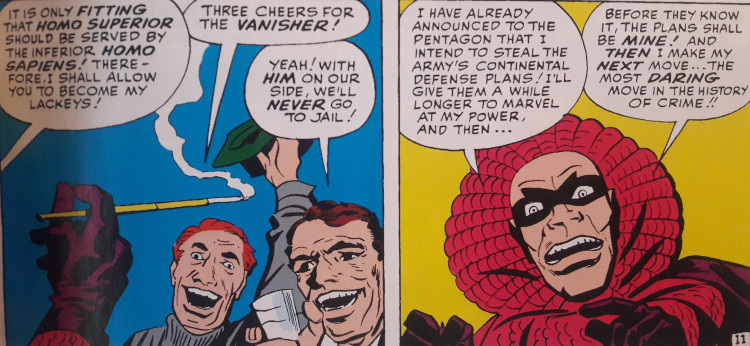

But this idea extends beyond the core Xavier/Magneto dynamic, and this is where it starts to wobble. Early issues introduce villains like the Vanisher and the Blob, who also seem 100% aware of the homo sapien/homo superior dichotomy, even though they seemingly have no use for such associations. For the Blob in particular, a lumbering mountain of a man who seems as sharp as a brick, his uncanny (sorry) keenness for this philosophy feels out of character and unaligned with the villain’s rather simplistic desires.

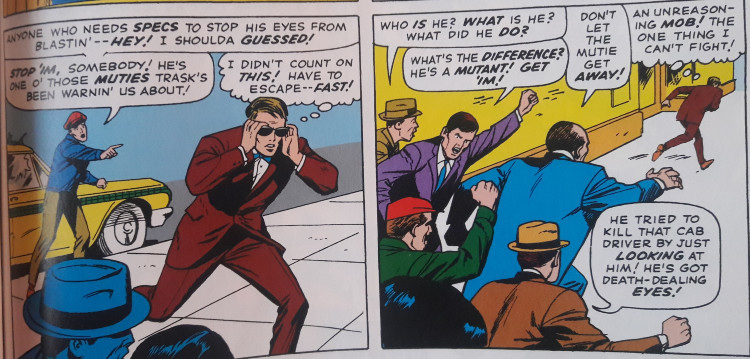

I understand Lee and Kirby’s idea, how they wish to depict this branch of humanity as different and “other” from the rest of mankind and utilize that central conceit as a metaphor for racial tensions. Problematically, the argument becomes unconvincing when “mutants are evil” is treated as a fact that, essentially, almost every character you run into understands and has no qualms with. Almost every man and woman in street scenes despises mutants; the heroes are terrified at the thought of exposing their true natures; Professor X discusses the stigma as if his students are engaged in a type of war with the rest of mankind. The theme feels far more universal than it should be considered. It’s an “us vs. them” mentality taken to extremes, where the “us” are six people cloistered in a school and “them” is the rest of the world’s population. Talk about uneven odds.

Lee and Kirby, as most readers know, were attempting to insert a racial dialogue within the series, how acceptance of another individual (or race of people) should trump hating or persecuting someone because of their differences. But, in my opinion, they lean into the notion far too heavily and immediately. The series lacks subtlety and sophistication--if you’re Average Joe, you probably hate mutants. You’ll probably throw rocks at any one you see. You’ll probably worry that your own kid has some sort of mutation. Occasionally, a character (usually a high-ranking military official or police officer) will see how beneficial the X-Men are, shake their hands, and offer up a quick “You’re all right in my book.” So, I guess, not everyone the X-Men meet is a jerk...but Lee and Kirby rarely offer any middle ground. Future stories will, thankfully, address the idea in a more complex manner, allowing some gray to seep into the X-Men's yellow-and-blue costumes.

Compounding this central notion is how ridiculously straightforward Lee and Kirby present it. Think on this concept for a moment: “older, rich gentleman trains empowered teenagers to become a paramilitary group sided against malignant forces of evil.” Under Lee and Kirby, what you see is what you get. Professor X is legitimate in his proselytizing about human/mutant relations and earnest in his desire to keep the X-Men well-trained. There’s no foreshadowing, no hidden intentions. Xavier has, particularly in more recent years, become less than a shining knight in armor, but he’s the real deal in these original stories.

Now apply the above premise to something like the Umbrella Academy. Perhaps it’s simply the times in which these stories were written, but in a show like Umbrella Academy, the premise isn’t as simple. Yes, Sir Reginald Hargreeves adopts several infants, raising them as his own and training them (or most of them) in the use of their superhuman abilities. But he’s got plans and counter plans, hidden secrets and desires that he never tells his kids. He’s no paragon of love and care like Professor X. The premise, therefore, isn’t as simple or easily laid out. These days, you’ve got subplots and plot twists and hidden agendas. One would expect, if the X-Men were created today, Xavier would follow the same pattern. Clearly, the brilliant and rich telepath has some dark secret, right? But no. He’s genuine, his desires are real. What could easily devolve into a twisty narrative about a distant instructor running a shady school is made plain. X-Men is not the series you expect it to be.

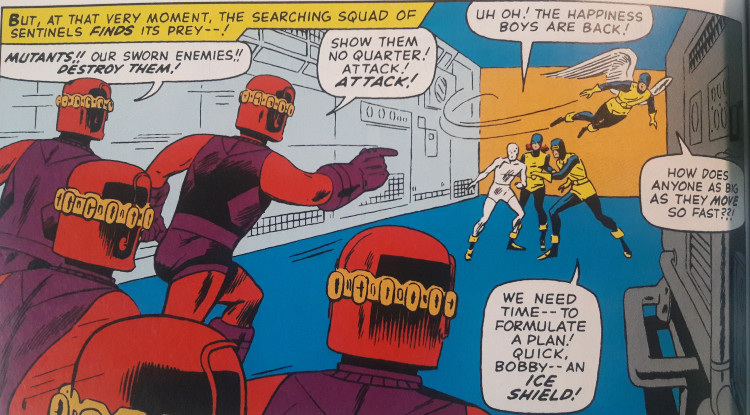

The racism metaphor aside, early issues of the series tend to be a bit repetitive. The X-Men encounter a potential mutant and usually fight Magneto or his lackeys to decide that new mutant’s fate, Professor X typically coming in at the clutch to offer aid. I’ve read at least one review of these stories which found the premise to drag on, and though I agree that the first handful of issues contain this X-Y-Z style of plot development, the series actually shifts gears more quickly than I imagined. Though the X-Men engage characters such as the Vanisher, the Blob, Namor the Sub-Mariner, and Ka-Zar of the Savage Land in this manner or a similar fashion, the rest of the issues have some genuinely entertaining tales, with premises that fluctuate nicely to inject uniqueness into the narratives being told. About halfway through this Epic Collection, Lee and Kirby deliver a one-two punch focusing on the Juggernaut and the Sentinels. These back-to-back narratives take up five issues of the volume in total yet represent the strongest material Lee and Kirby deliver. Deviating wildly from prior premises, the issues engage with fascinating plots, terrifying villains, and genuinely great characterization. The Juggernaut's personal vendetta against his step-brother Charles Xavier is developed nicely, especially as the armored colossus (no, not the other guy) smashes his way through the X-Men's defenses; the Sentinels represent Lee and Kirby's most nuanced contribution to the racism metaphor, as a scientist realizes the danger his fanatical hatred and fearmongering cause when his giant, mutant-hunting robots run amok. From here, Lee and Kirby are on a roll through the rest of the volume, abandoning one-and-done issues for longer, sequential arcs that feed into another in a more organic manner.

As I stated previously, the differences between these early issues and Claremont’s later tales are fascinating to examine, particularly in seeing how the team and their core characteristics develop over time. Yet even within these first 23 issues, you see how Lee and Kirby reassess and rethink their characters. Professor X initially tells the team he lost the use of his legs in a childhood accident, a fact which is later retconned to an encounter the adult Xavier had with villainous alien Lucifer. Cyclops is called “Slim Summers” in the first issue, his name changing to Scott shortly thereafter (with “Slim” becoming a recurring nickname). And, in perhaps the series’ most infamous moment during Lee and Kirby’s run, Professor X mentally professes his love for Jean Grey, one of his students, a detail which has been lambasted on the internet and was, thankfully, swiftly dropped.

As the series progresses, characters, too, are allowed to grow. Jean Grey, who has certainly been seen as the token female team member of the X-Men, nevertheless gains greater mastery over her abilities. Beast demonstrates his intellectual prowess. Iceman, the youngest member, expresses his desire to prove himself to his older teammates. Angel, whose alter ego is rich trust fund baby Warren Worthingon III, expresses decent snatches of humanity towards his fellow X-Men which pull him away from a potentially shallow depiction (one of my favorite moments in the whole volume has the winged teenager remark how nice it is to see a rare smile from Cyclops, showcasing empathy towards his fellow student). On the villains’ side, Lee strings together an overarching plot for former villains Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch as the siblings combat their allegiance to Magneto and his Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.

Cyclops, sadly, is the X-Man who receives the least alteration. Lee sets him up as the stoic “deputy leader” of the X-Men, second-in-charge when Xavier is around and fully in command when the professor is absent. This, coupled with his fear over losing control of his destructive eye-beams, turns Scott Summers into a burdened young man, similar to a Peter Parker. Yet where Peter’s situations are largely conditional and turn the hapless hero into a constantly down-on-his-luck teenager, Scott’s own pains are self-inflicted. And where Peter is able to get away from his issues by turning to his Spider-Man persona, Scott is the same character inside and outside the costume. He doesn’t change, and his constant pining for Jean Grey becomes repetitive and boring. Not that I think Stan Lee was wrong in inserting the romantic tension between the two--unbeknownst to the one, the other feels just as deeply--but his attempts at “Will they?/Won’t they?” drama lapse into uninteresting drivel. Their unexpressed emotions just drift through panels, with each character constantly reflecting on how it’s never the right moment to discuss their feelings. I’m amazed Professor X, powerful mental mutant that he is, never just sits the two of them down for a conversation to defuse the tension. That’s all it would take.

To you, my reader, it would appear that I’ve analyzed this volume with a decidedly cynical lens, dragging the X-Men’s basic premise through some muddy waters. I’ll admit that’s true. Lee and Kirby’s setup for the series feels outlandishly broad, but once you pierce that grim cloud cover, rays of light shine through. As I previously remarked, the stories themselves, especially those later in the volume, stand out more. Within their wonky background, Lee and Kirby maneuver themselves well, crafting fun stories with engaging villains. I don’t necessarily mean to indicate that Lee and Kirby’s intention, setting up mutants and their persecutors as analogues for racial tensions in the United States, is objectively poor or lacking; on the contrary, as I mentioned, Lee and Kirby are often not subtle enough. The work of writers such as Chris Claremont will do a much smoother job at relaying the X-Men’s connections to real-world racism.

But Lee and Kirby, for all their foibles, are genuine in their remarks. “Beware the fanatic!” the end of the Sentinel saga proclaims. “Too often his cure is deadlier by far than the evil he denounces!” The writer/artist duo are honestly attempting to portray the evils of hatred and xenophobia, and even if it means having the Blob, of all people, understand the depths of the sapien/superior philosophical clash, then by golly, they’ll get their message across. X-Men is definitely heartfelt, for all its openendness.

What we’re left with, then, is a rather torn volume. On the surface, you get a collection of issues that marks one of Lee and Kirby’s less successful series. Some repetitive plotting, in-your-face preaching, and wonky relationships hinder what could have been, at the time, a highly engaging group book. Yet, behind all the obvious flourishes, genuinely gripping stories and conflicts meander through the pages. Within the messy framework are gorgeous details. It’s the way Angel regards Scott Summers. It’s how Iceman yearns to impress his older teammates. It’s when Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, after several issues of debating their servitude to Magneto, decide to finally break ties with the master of magnetism. It’s in the heated rivalry between Juggernaut and Professor X, as Cain Marko smashes through defense after defense to get revenge on his crippled stepbrother.

I don’t have the greatest recollection of the stories after these, so I’m excited to jump into the second and third Epic Collections. Though I don’t believe I’ll ever be convinced these stories are anywhere near as fabulous as Claremont’s, I hope to gain (or regain) an appreciation for these older tales and better understand how they shaped the stories to come.