Distinguished Critique: Deathblow Review

A step up from its predecessors, these twelve issues of Deathblow tell a fairly well-constructed, complete narrative, even if one subplot is sorely mishandled

—by Nathan on June 22, 2024—

I've got a tricky one here for you all today.

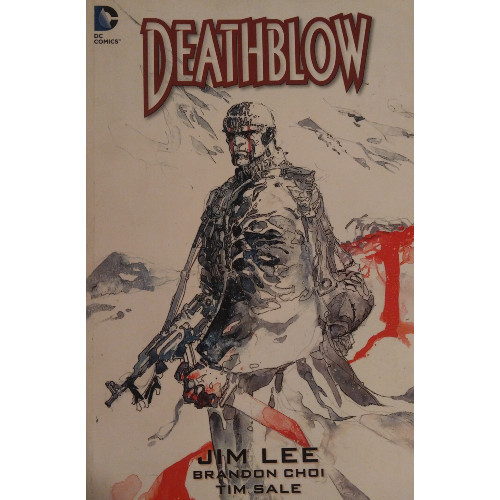

Deathblow was a character (and a series) originally created in 1993 by Jim Lee and Brandon Choi as part of Lee's WildStorm imprint, his branch of the burgeoning Image Comics company. Which should make the character's (and series') inclusion under my own imprint of decidedly-not-Image Comics reviews perhaps a tad perplexing. This is, after all, the DC Universe corner of Keenlinks. Why's a guy who debuted as part of Image Comics included here?

Thanks for asking. Or at least for listening.

During the latter months of 2023 (and a little into 2024), I dove into the waters of early Image Comics through my "Random Reviews" series, finding the depths shallower than anticipated. Though I emerged from the water with my spine intact, I turned around and almost immediately leapt back in, feet first this time, curious about post-"initial Image" Image series. Who else joined the ragtag original seven creators and made their voices known as part of this growing group of independent creators? So far, I've churned out a review of the earliest issues of Dale Keown's Pitt. I looked through a few sites, found the chronological order in which first issues of those earliest Image series were published, and discovered that, shortly after Image released the first issue of Pitt, they plopped down their latest creation: Michael Cray, the mercenary known as Deathblow.

Jim Lee sold WildStorm to DC in 1998, including characters such as Deathblow and WildC.A.T.S. So even though we're on the DC side of things, that's merely reflected by the company logo sitting pretty in the top left corner of the trade's cover. I hope you don't mind the brief tour away from the origins of bat-eared detectives and Amazonian warrior women. Make no bones: narratively, we're still in wild Image waters, the land of fin-headed dragon men, mercenaries burdened by guns and pouches, and ever-increasingly bleak displays of violence.

Yee-haw.

Deathblow

Writers: Jim Lee, Brandon Choi

Pencilers: Jim Lee, Tim Sale, Trevor Scott

Inkers: Jim Lee, Trevor Scott, Tim Sale, Sal Regla

Colorists: Joe Chiodo, Linda Medley, Claudia LaRue, Wendy Broome, Paige Apfelbaum, Ben Fernandez, Monica Bennett, Digital Chameleon, Wildstorm FX

Letterers: Mike Heisler, Todd Klein

Issues: Deathblow #0-12

Publication Dates: April 1993, August 1993, February 1994, April-August 1994, October 1994-January 1995, August 1996

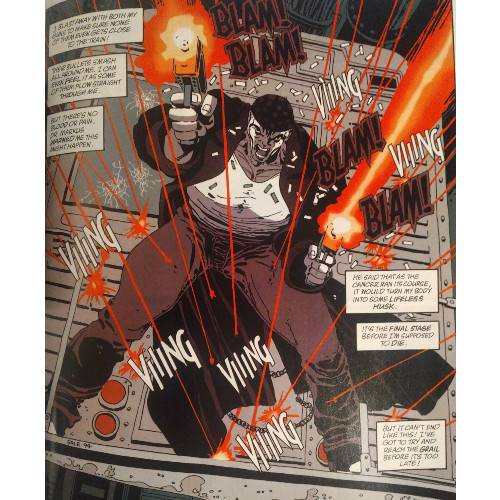

There is a sense, as you close the final pages of this volume, that a certain amount of thought graced the development of Deathblow. This feels like "Guy Strapped to the Gills with Guns" 2.0. Now that the earliest series had given audiences their fair share of big people with big guns and a whole lot of shootin', maybe Image could find their place in the comic world by offering somewhat more cerebral fare. They'd gone through their angry, trigger-happy adolescent state, and with this "second wave," could emerge more mature. While Superman was being bludgeoned to death by a guy with pointy elbows and Spider-Man dealt with the slimmer, more vicious copycat version of his then-greatest foe, maybe Image could scrounge up books for the more intellectual reader.

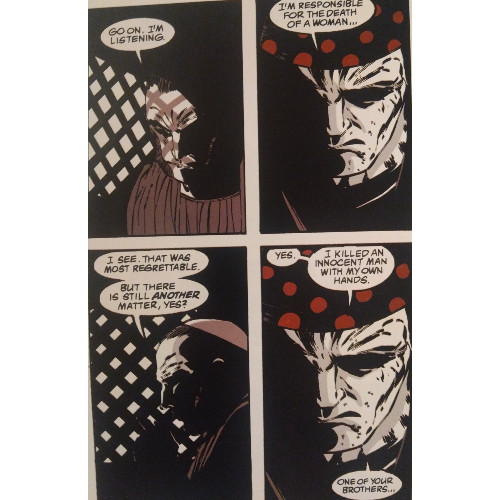

To the credit of its assembled creators, Deathblow strives to break the bonds of simplistic storytelling and over-the-top violence for the sake of over-the-top violence delivered by its brethren. By focusing on a singular character rather than teams of mercenaries, Lee and Choi find a depth that Erik Larson and Jim Valentino also strove for in their books. Michael Cray isn't quite the "assassin with a heart of gold," but he's at least a "killer with a conscience," driven (somewhat) by a religious, specifically Catholic mindset. There are efforts to pull in religious theming to undergird Michael's morality–how does he balance belief with his selected occupation? How is he to reconcile his past with his present? Can he fix the relationships he's sundered because of the blood soaking his hands?

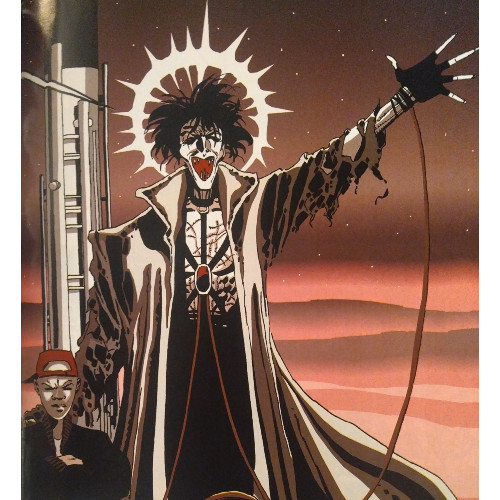

Lee and Choi more adeptly maneuver their theming than Todd McFarlane does in Spawn, for example (or that really ridiculous two-part Spider-Man story where Spidey fought the Demogoblin alongside Ghost Rider). The series' primary villain wishes to bring literal hell on earth, and where religious iconography and dialogue is skewed heavily by McFarlane towards the unbearably ridiculous, Lee and Choi maintain a somewhat consistent tone. It's over-the-top, but it permeates the narrative, found not just in a few cliche statements but in the makeup of our primary characters, both heroes and villains. The assassin with a religious background is tasked with protecting a Messiah character while assailed by literal demons. It's goofy, but it works because the creators stick with the plot. They're true to the narrative through all twelve issues, true to Michael's character as he wages an internal war through narrative text boxes as he struggles against external forces.

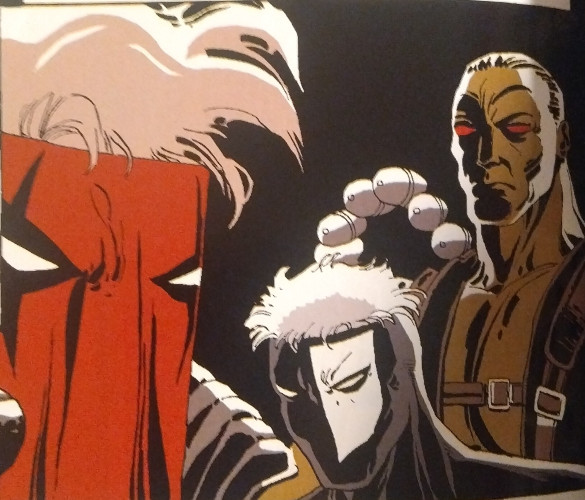

Tim Sale, who provides the bulk of the art in this volume, is to be praised for assisting that consistent tone. Fairly early in his career (these issues early predates his Long Halloween days), Sale has nevertheless developed his signature style already–a few of his female characters call to mind Gwen Stacy and Mary Jane Watson from Spider-Man: Blue; a demon possesses the similarly elongated face of his Joker, and he somehow makes all the 90s grit and look fairly cool. This isn't Youngblood or Cyberforce, where everybody's muscles bulge and strain against their armored carapaces. The decision to keep coloring limited to primarily reds and some grays mixed in with the black and white gives the comic a distinct feel, providing a less overwhelming palette while allowing the comic's story of mercenaries and serial killers to feel grounded in-between scenes of demonic wrath.

Where Deathblow falters, quite abysmally, is in its execution of a fairly significant subplot: as the series begins, we are offered a very unique layer of conflict for a highly important character, conflict which drives their motivations throughout the story. Shortly after we are introduced to this problem, the audience, separate from most of the cast, is told this troubling fact is a fabrication, mere trickery. This is pages after we are introduced to what becomes the defining impetus for this character's actions, and while one could argue the use of dramatic irony, I can't defend that position. I felt disappointed. Suddenly, any time the character reflected on their plight, I shrugged my shoulders, which were already stooped. It's not real, my mind replied. Why should I care? And it's not even the fabrication I'm disappointed by so much as it is how soon we are informed of the fabrication. This revelation could have been saved until later, compounding the narrative at a crucial point where this character learns they were misinformed, misguided, tricked. I actually don't think they ever learn this fact, so why toy with the fabric of our understanding? The authors, far too quickly, remove a principal motivation for me rooting for the character, and when a later moment arrives when they believe their problem is resolved, I got stuck in the lie they never learn and found myself more confused than gleeful.

Wisely, Lee and Choi keep Deathblow largely to itself. Characters such as Savage Dragon and Pitt are referenced, a location is used which also appeared in WildC.A.T.S., and Lee's character Grifter and Whilce Portacio's Dane from Wetworks aid in the arc's final conflict. Lee and Choi don't do much to place the comic within the larger Image timeline or universe, and though we're given a sense Michael's history is wound within certain events not yet detailed, we don't need to know those events specifically to understand the camaraderie between him and a few other characters. He's buddies with one of the golden guys from Wetworks. That's all I need to know.

Though Deathblow ran far longer than the twelve issues presented in this volume, I'm glad we're given an entire arc here. No pesky cliffhangers or unresolved questions. This could be its own series, as Lee, Choi, and Sale give us a decent plot fully resolved by the final page. As far as I'm aware, no additional issues from this specific series have been collected, though Deathblow has seemingly enjoyed a longer history. Michael's struggles feel adequately presented and fought through as he comes to terms with his past and present circumstances. Supporting cast members are left in a place where they could return if necessary (and maybe they did?) but don't need to. The completeness of this arc is much appreciated, especially as I haven't much interest in exploring many of these series (with perhaps an exception or two) beyond their initial collected issues.

Deathblow is not a perfect series. I will be, for a long time, annoyed with how a particularly compelling subplot is mishandled, in my view, from essentially its introduction, turning what could have been a very interesting development for a character into a dead end street before much pavement was laid. And the writing isn't perfect, in either dialogue or storytelling. But the bar I've set myself for early Image is so low that there shouldn't be much trouble stepping over it. I'm not going to throw this onto my list of "Best Comics from the 90s" alongside Long Halloween, Infinity Gauntlet, or Marvels. But I can say I closed the cover largely satisfied, that this series avoids a critical deathblow despite its title.