Distinguished Critique: Watchmen Review

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons construct a richly detailed magnum opus which remains highly readable and culturally influential today

—by Nathan on May 18, 2023—

How the heck do you review what’s considered to be the greatest comic of all time?

Over the last few decades, Watchmen has received such acclaim and such praise that it’s regularly ranked at the top (or at least near the top) of "Greatest Comics" lists by a whole ton of websites and bloggers. It won both the Eisner and Hugo Awards. It’s been turned into a movie (with middling results), spawned a sequel (which I will review later) and several prequel issues, and has its own TV show. All centered on this twelve-issue limited series from the 80s. I mean, Squadron Supreme, I love ya, but I’m sorry, you don’t have the staying power this piece has.

So I’m not gonna try and compete.

This is simply a review, my thoughts and reactions towards the Alan Moore/Dave Gibbons classic. I don’t intend on gushing praise or loading on piles of historical significance. I’m not wholly interested in its importance to the community at large. I’m curious about my perspective on the story, the characters, the artistic details. All I’m going to do is write about that. Maybe you’ll enjoy it.

Watchmen

Writer: Alan Moore

Penciler: Dave Gibbons

Inker: Dave Gibbons

Colorist: John Higgins

Letterer: Dave Gibbons

Issues: Watchmen #1-12

Publication Dates: September 1986-October 1987

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

As I closed the final chapter of Watchmen, I found I enjoyed the pieces of the puzzle over the finished image.

Moore and Gibbons construct an incredibly dense, complex piece of literature over Watchmen’s twelve chapters. The story is wonderfully complicated, though not inconsiderate towards the reader. Moore continually references elements sewn in earlier, creating a cast of characters and plot points which work their way methodically through each installment. Scenes are revisited from the perspectives of others, offering more insight into the minds and motivations of our protagonists.

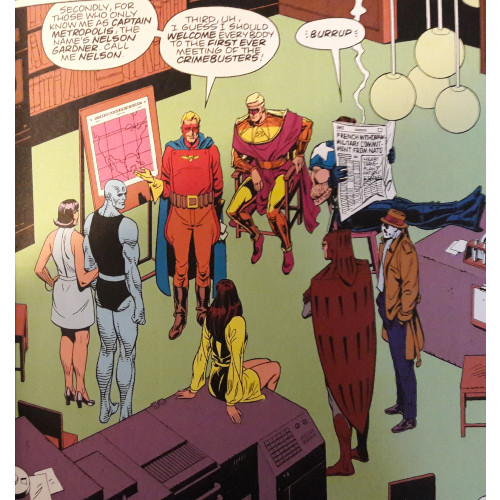

Take the first meeting of the “Crime Busters,” for example. Captain Metropolis, former member of the disbanded superhero team called the Minutemen, attempts to pull together a new band of heroes. Fellow Minutemen teammate the Comedian attends, along with newer heroes such as Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, the second Nite Owl, and the second Silk Spectre. As Moore revisits this integral moment, retold from different characters, you see different angles. You learn of Spectre’s initial infatuation with Dr. Manhattan, Dr. Manhattan’s then-girlfriend Janey’s jealousy, Ozymandias’ thoughts and reflections, and an interaction between Spectre and the Comedian immediately thereafter.

Moore excels at this type of intertwining, and his ability to reflect back on past events and their relevance to the present solidifies how well-constructed Watchmen is. This truly feels like an epic saga, with each piece feeding coherently into the next and capably offering further insight into previous chapters.

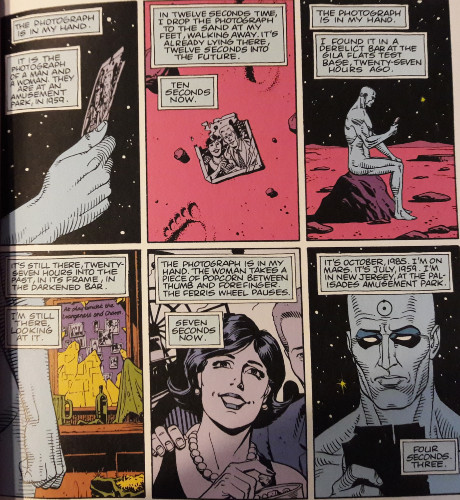

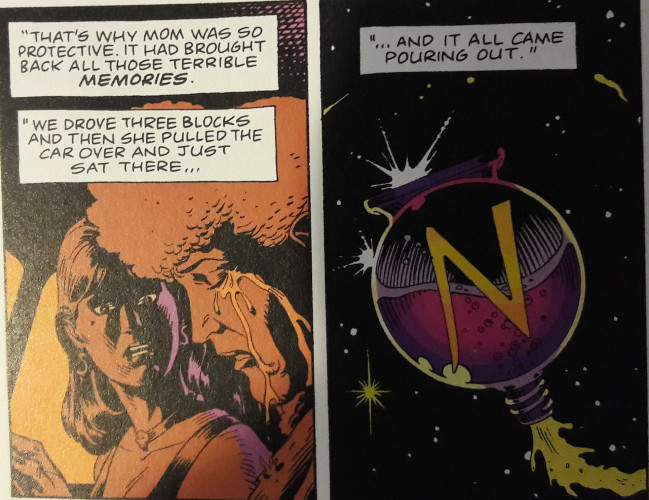

Amazingly, each chapter is also allowed time to breathe, and as I mentioned previously, I would argue I enjoyed the individual issues over the entire narrative. Moore and Gibbons are ridiculously creative at making each chapter unique, offering a specific focus and allowing the larger narrative to flow through these smaller lenses. The second issue, for example, is largely dedicated to our cast’s reactions to the Comedian’s recent murder and their reflections on him, both good and bad. Two issues later, Moore and Gibbons delve deep into Dr. Manhattan’s origin, framing the issue around Manhattan’s own perception of time. Achieving godlike abilities, Manhattan no longer sees time in the linear fashion we do; thus, the narrative skips back and forth through the decades, drawing parallels between scenes and creating a tapestry of woven chronological threads (a friend of mine compared it to Arrival). Each chapter is fantastically specific and planned out, developing the overall story as needed but allowing the reader to realize the moments, pieces, and seconds are just as important, if not more so, than the overall monument these men construct.

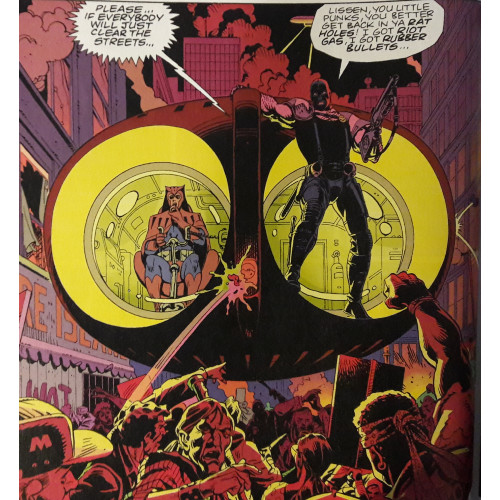

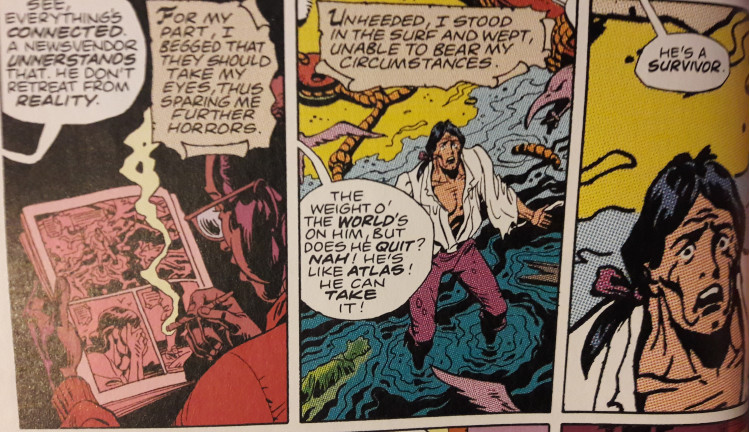

Gibbons’ ability to craft striking figures and sequences provides the story's necessary gravity. His people are real, his actions feel dynamic and grounded (or as much as they can be in a world where a god looks like a member of the Blue Man Group). I was especially impressed at how organically Gibbons blended Moore’s dialogue with his art. In many panels, Gibbons provides an artistic balance or parallel to Moore’s narration or actions. A retired superhero passes in front of a sign for a car mechanic that specializes in “obsolete models.” A newsstand owner talks about surviving war while a young man reads a comic book about a shipwreck survivor. Ozymandias talks about putting an end to warfare, his dialogue bleeding into a panel that sees police showing up to stop a physical confrontation

One cannot overstate the ridiculous number of seemingly insignificant details Moore and Gibbons feed into the pages. A building behind a newsstand featured in several issues plays an incredibly important role in the story’s climax. News reports of a missing author seem utterly inconsequential until the story’s final chapters. One of my favorite details involves a character wondering if they could ever catch a bullet only to do so a few pages later when they’re shot at. The fact this character plays dead to only then dramatically reveal the caught bullet only adds to the moment. These “seemingly insignificant” details are, over time, revealed to be much more pertinent to the unfolding drama than originally perceived. You cannot take the minuteness or moments of Watchmen for granted. This forces you to pay attention, to keep your eyes sharp and your memory clear.

Some of the details are plot-related, several of them are not, but even the most minute moments are important to capture. These details show the craft and care which Moore and Gibbons put into their narrative, and the fact they include so many discreet visual details for the reader to find and connect makes the story all the more engaging. It’s a “Where’s Waldo?” of comics, where the “Waldo” is all the different images and details Gibbons slips into the panels and pages to heighten the narrative and broaden the world he and Moore have created.

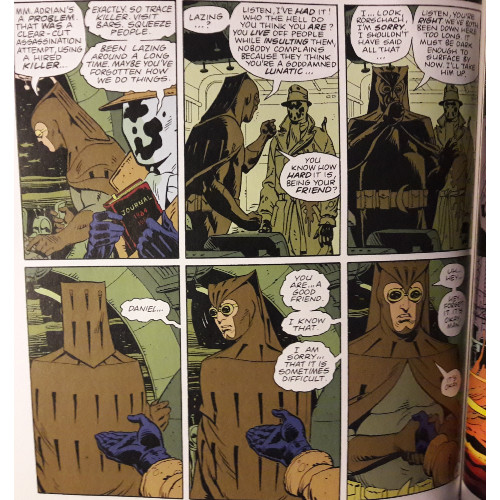

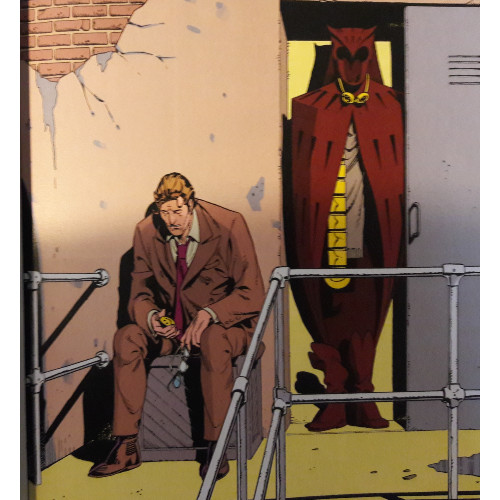

Within the narrative and written between the details are several dynamic characters, their individual stories well-wrought and woven throughout the larger drama. Dr. Manhattan struggles with his godlike inhumanity; he’s almost robotic, cold and distant. Even in the company of others, he’s preoccupied and matter-of-fact, yet so enormously powerful that when his emotions rise to the surface, he becomes capable of immense destruction. Rorschach speaks in stilted grunts, his identity kept unknown for a good chunk of the plot and his blend of brutal actions and noble intentions making for a complex individual. The second Silk Spectre grapples with issues of identity and parentage–does she follow the path her mother has for her or does she choose her own road?

Each character comes with a problem, and over the course of the series, Moore and Gibbons tackle each of those issues. Dan Drieberg, the second Owlman, has hung up his cowl and goggles; we quickly learn he’s unsatisfied with his “new normal” and soon becomes embroiled back into the spandex game. Spectre struggles with her previously mentioned maternal, as well as her relationship with Manhattan, finding potential escapes from the seemingly burdensome pressure others inflict on her. Each character feels truly realized, with emotions and struggles to help the audience become attached.

“Attached” but not “endeared.” Fantastic as the characters are, and as relatable as they can be, they didn’t leave me enamored. I didn’t finish Watchmen and initially reflect on how much I enjoyed our protagonists. I wrestled with how much I actually cared for each of our main heroes–I certainly appreciated their quirks, complex personalities, and narrative importance. But in terms of sheer “likeability,” I found myself a tad lost. It’s not that Moore and Gibbons’ heroes needed to be funny or nice like practically any main character out of a Marvel film. But each of them have weaknesses or flaws which detract from the character rather than enhance them. Dr. Manhattan is a bit too cold. The Comedian is a straight up jerk. Rorschach is perhaps a bit excessively grim at moments. I just struggled with looking over the cast and putting a finger on “Yeah, he/she is my favorite Watchmen hero.”

Despite this, I found the artistry wonderful and the narrative kept me hooked. The characters, to me, weren’t as important as the tale and world unfolding around them. A weird sentiment, I’ll admit. So often, it’s the characters who drive the story, and though this is certainly true with Watchmen, I found the series’ events more intriguing than Moore and Gibbons’ dramatis personae. I was far more invested in the details and minutiae of the plot, wondering how Subplot B or C would catch up with Main Plot A. Even though I went in with some of the major plot points spoiled–thanks, internet–I was amused watching the story build to its climactic revelations. In hindsight, Watchmen would have been even more fun to read without any knowledge of the source, but regardless of having some surprises spoiled, I enjoyed the plot all the same.

For readers unaware of the series, I would caution against reading much about it beforehand. Several videos and reviews seem loath to avoid discussing at least two major plot developments, and I can’t blame them. These revelations are incredibly important to the narrative overall, and I’ll admit that by having prior knowledge, I found I noticed certain details I wouldn’t have otherwise. Still, heading into Watchmen oblivious (or as oblivious as one can be) would make for a different, perhaps even more engaging reading experience.

There's a reason Watchmen has remained as influential as it has been, and there's a reason why the comics industry shifted towards a darker tone in the mid-80s, perhaps in part reacting to this series (as well as contemporary The Dark Knight Returns). Yes, the industry may have eventually taken the wrong lessons from Watchmen, churning out overly serious yet vapid narratives which misinterpreted violence and brutality for poignancy and producing "grimdark" stories such as "Maximum Carnage," "Knightfall," "The Death of Superman," and others. Still, writers and artists have rightfully analyzed Watchmen and some of its more substantially deep and mature peers (such as "The Killing Joke" (another Moore-penned DC narrative), "The Death of Jean DeWolff," "Kraven's Last Hunt," and "Batman: Year One"), producing content which understands the connection between complexity and shadow. "Mature" may mean "slap a content warning on this sucker," but if it's only about the level of grim gore a writer can inject into their narrative, the point has been missed. "Mature" should be more aligned with "complex" or "realistic," where writers can tackle subjects and more adult-oriented themes without resorting to blood and guts. Yeah, violence may pervade these stories–check out Mark Millar's Old Man Logan, Grant Morrison's WE3, Brian K Vaughan's Pride of Baghdad, or Robert Kirkman's Invincible for good examples–but they offer more than blood-soaked panels. They offer characterization, clever world-building, and perspectives which comics prior to Watchmen may not have allowed.

Do yourself a favor and pick this up. I often decry jumping on the literary bandwagon, wondering which stories are famed because they’re actually good vs. being lumped into a subjective popular conscience and perpetuated as “good” for decades. Watchmen falls into the former category. The detail alone makes it worth a second reading. It’s not my favorite comic (I still have that issue with the characters, though perhaps a second reading is necessary to convince me otherwise), but I enjoyed it more than I previously imagined. For some, Watchmen is “good.” For me, at the moment, it’s “good enough.”