Crawling Back: Amazing Spider-Man #121 Review (The Osborn Prelude, Part 8)

Iconic for a singular, devastating moment, "The Night Gwen Stacy Died" is beyond notable for how spectacularly it creates tension surrounding that moment

—by Nathan on January 21, 2025—

In the introduction to my review of Amazing Spider-Man #39-40 (the issues where Spider-Man and the Green Goblin learn each other's identities and the first time Norman Osborn loses his memory), I summed the story up with a single sentence: "This is the big one."

Maybe I spoke too hastily.

That climactic confrontation is certainly a cornerstone chapter in the ongoing feud between the Goblin and the Spider, as it marks a significant turning point in their relationship. I also noted the issues end "the first chapter" of the Spider/Goblin war, and that is certainly true. After Norman's initial amnesia, the conflict has shifted: no longer is Osborn bent on becoming a kingpin of crime and controlling the New York underworld; he's more interested in the ultimate destruction of his most-hated enemy. And so, starting with Spectacular Spider-Man Magazine #2, his last few appearances have followed a different pattern–Norman remembers he was the Goblin, remembers Peter is Spider-Man, tries to kill Spider-Man, and then lapses back into his amnesiac self, with Peter left terrified the grinning gargoyle will someday claw his way out from the older Osborn's skull.

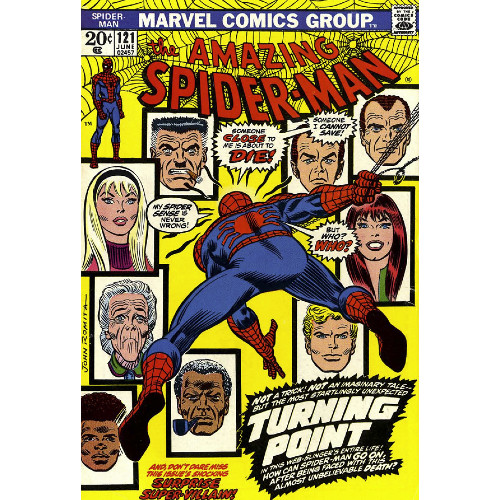

Today's review covers the first half of a second major turning point in this running battle between the costumed combatants and, more than the identity revelation, truly cements the Spider/Goblin war as a deeply personal conflict. Amazing Spider-Man #121 and #122 are significant from a historical standpoint–the issues, along with Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams' Green Lantern/Green Arrow run, mark for many fans the end of the Silver Age. From a narrative perspective, the issues are the culmination of a few impactful subplots, serve to yank that aforementioned war into a darker, more personal battlezone, and mark the first time a writer other than Stan Lee contributed to the Spider/Goblin conflict (though this won't be Gerry Conway's only contribution). Most significantly, and most well-known, #121 specifically includes the famous (infamous?) death of an important character in the Spider-Man mythos, one which has not been overturned (and we're not counting clones!) even today, over fifty years later.

As each issue is so culturally impactful for different reasons, I have elected to not mash them together in one post covering the whole story. I'm parsing these out, taking time to examine each chapter in greater detail, following every twist, turn, and web-line.

"The Night Gwen Stacy Died"

Writer: Gerry Conway

Penciler: Gil Kane

Inkers: John Romita and Tony Mortellaro

Colorist: Dave Hunt

Letterer: Artie Simek

Issue: Amazing Spider-Man #121

Issue Publication Date: June 1973

The story goes that Gerry Conway approached Stan Lee while Lee was packing for a business trip to Europe and asked if Gwen Stacy could be killed off in Amazing Spider-Man. Lee, distracted, replied affirmatively, only to be completely shocked when he returned to America and heard about Gwen's death. Lee wasn't the only one astonished at this turn.

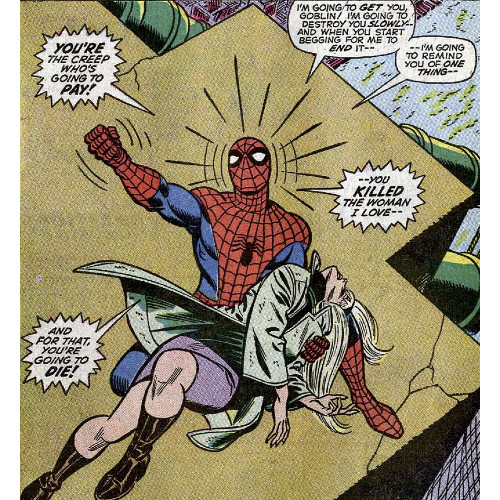

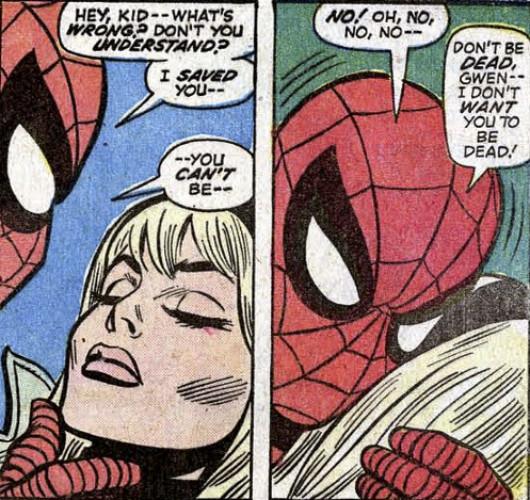

ASM #121 is coy about this particular development, saving its well-known title for the very end of the issue, featuring it at the bottom of a full page image of Spidey cradling Gwen and swearing revenge at the Green Goblin. A remarkable cliffhanger, especially for 1973, where it was uncommon for a major supporting cast member in a comic book to be murdered. Sure, famous folks had died (or "died") before–Bucky Barnes, for instance–but here was a regular woman, with no powers whatsoever, who seemed secured in her position as Peter Parker's girlfriend. Who'd suspect any harm would befall poor Gwen Stacy?

The shock of the issue may have worn off during the decades, but the weight and impact of this narrative has not. Skirting around its most famous moment for a second, I want to analyze other aspects of the issue first, focusing on how they build to the finale.

Conway deftly integrates current conflicts into the issue as a basis for what happens later, tying these pieces together skillfully to have us believe that Gwen's death really is a result of these factors. Peter is not at his fighting best after picking up the flu while fighting the Hulk in Canada. Harry Osborn has relapsed into taking drugs, frustrating his father. Norman is facing mounting business concerns and blames Peter, MJ, and Gwen for his son's worsening condition. A few previous interactions with Osborn had caused Peter some concern, the young man wondering how long the older man's fragile tether to reality could hold.

Not long, it turns out.

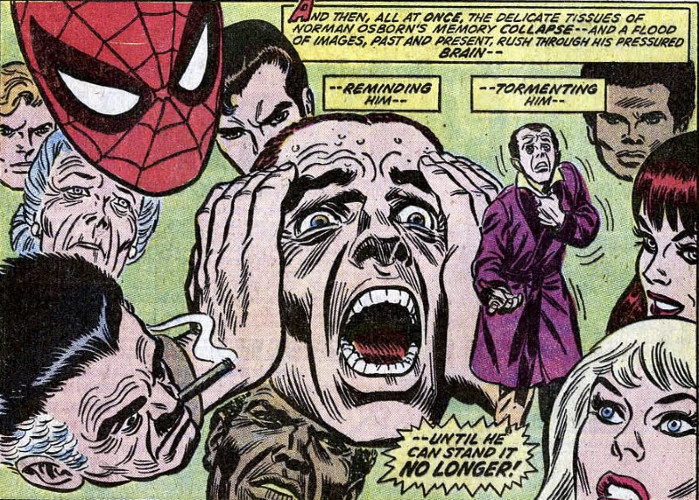

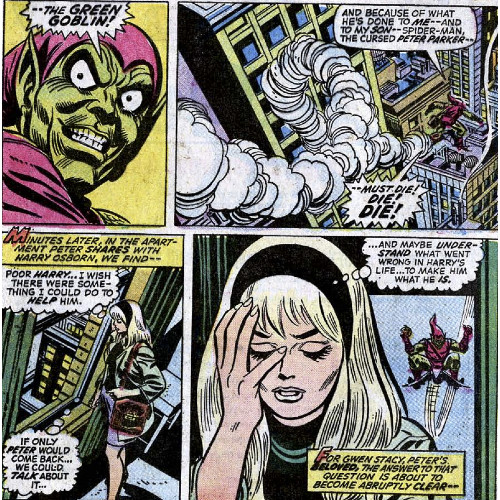

Each of these pieces help the conflict between the Goblin and Spidey develop organically across the issue. When Norman's psyche finally shatters, it's not just a singular moment to get him back into the green-and-purple guise of the Goblin. It's after several pages of worries, concerns, frustrations that cause him to sweat, grow angry, act harshly. You get the sense Norman has failed to place himself in a healthy state of mind and properly handle his concerns. This isn't just "Norman sees a photo of Spider-Man and remembers who he is." This is "Norman's problems lie deep within his mind, and he, wholly separate from his alter ego, allows his sense of self to shatter so the Goblin can return." It's a more methodical way for Conway to drag the villain into the conflict than Lee developed, tied directly into previous stories and conflicts.

Gil Kane's ability to depict the tormented Mr. Osborn is commendable across the issue. From the beads of sweat dotting Osborn's brow, to a shot of Norman standing in shadow looking silently out a window, to the second his psyche snaps again, Kane conveys a host of detrimental emotions as Norman slowly spirals back into madness. The image of Norman, staring ahead, hands clasped to the sides of his head, mouth wide in a silent scream like a modern equivalent of a certain Edvard Munch painting, feels more at home in a horror comic than a superhero thriller, more than adequately encompassing all the thoughts and emotions pounding against his skull.

Conway–who, I'll remind, is writing the Goblin for the first time–wonderfully shifts Norman's personality as soon as he dons the mask. Gone is the sweating, sour businessman who feels his world is imploding. With the mask comes a sinister confidence, a single-minded purpose to eliminate who he believes is the source of all his troubles. Spider-Man is, in the Goblin's words, "the man who keeps me from myself," an insightful description honing in on Osborn's sense of identity. Much like a certain Dark Knight Detective feels his rich alter ego is his facade, so does the Goblin believe he is hidden beneath Norman's visage...the major difference, of course, being that if Norman's accident hadn't caused his mental breakdown, he'd be a perfectly healthy businessman and father. Lee understood this, too, but Conway more deftly connects the Goblin's supposed suppression to Spidey's involvement in his schemes, and finally feeling freed, takes a twisted step to raise the stakes between himself and his foe.

Understandably, modern readers may interpret this "twisted step" differently these days: Gwen becomes a victim solely because of her connection to Peter, through no fault of her own, and most certainly is considered an early example of "fridging." Her death, beyond just the shock of it, is a horrible tragedy, not just because of its impact on Peter, but because of the utter unfairness of the situation. I don't recall how much Gwen was allowed to grow in her own agency beyond "Peter Parker's girlfriend," but we're talking about a character who had been around since Peter's first day of college, who spends her last waking thoughts concerned about Harry as his father sneaks up on her on his glider. She lost a father to Doctor Octopus, left for Europe to clear her head, and reunited with Peter to consider their future. The Peter/Gwen relationship was a long-running subplot with far more impact than Peter's interest in Betty Brant, Liz Allen's interest in Peter, or even Mary Jane's flirtatious attitude towards "Petey."

I've heard it said Conway selected Gwen to die, over characters such as Aunt May or Mary Jane, because he (and assumedly other staffers) felt the relationship between her and Peter had stagnated; unless the two were going to get married, he felt there was nothing much more that could be done with the couple to generate interest with fans. This seems confirmed in a letter column a few issues later: in ASM #125, a response to fan letters enraged at Gwen's death notes that "there was nowhere else to take" the relationship, as "marriage seemed wrong." One could ask why a breakup wasn't elected as a less painful manner to split the couple, but a breakup would not have had the same emotional resonance.

Do I believe the creators were correct in killing Gwen? I do. I'm not going to toe some line and be wishy-washy about it. Outside the historical significance of Gwen's death, I feel the tragedy is handled well, depicted as an awful, seemingly unavoidable circumstance which is the culmination of various factors coming together to create a perfect storm. The death isn't necessarily teased elsewhere in the issue, meaning it is unexpected to the uninitiated reader, but it also doesn't feel completely random or done only for shock value. The next several issues of Amazing Spider-Man (a few of which I've touched on already, and at least one other I will explore) handled the fallout of Gwen's death, treating it with the attention it deserved. And time, though it hasn't always been the kindest to Gwen's legacy (thanks, "Sins Past"), has made this a singular, defining moment (call it a "canon event," if you'd like) in Spidey's history, depicting or adapting it in TV shows, movies, and video games.

This isn't a one-off event intended to bug Peter for a while before having him come to terms and moving on. "The Night Gwen Stacy Died" is a point of no return for the hero, for his other relationships, and for his conflict with Norman (as we will see in the next post). Creators have referred to it extensively, whether its David Michelinie having Peter wrestle with the memory before his wedding or Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale dedicating a whole limited series to Peter's first love. The fact that each of these instances refer to the situation as it happened and don't try to change or retcon it–this isn't Chris Claremont having Carol Danvers confront her friends over the events of Avengers #200 or the Phoenix revealed as an entity separate from Jean Grey–points to the power of the moment rather than the harm some may say it caused.

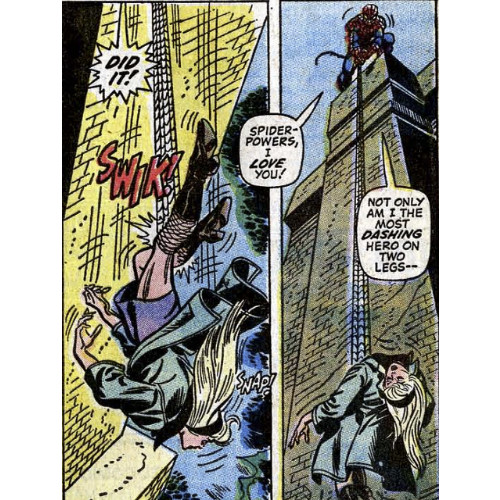

Beyond the historical impact, "The Night Gwen Stacy Died" is a well-written issue which should be recognized for the sum of all its parts–Norman's return as the Goblin, Harry's struggle with drugs, Peter's worries made tangible–than just the singular moment it's most famous for. Gwen's death is still weighty several decades later, but it's how Conway and Kane lay the pieces which build to the final confrontation that heighten Gwen's death beyond the final panels. There are small moments which work well on their own: Norman standing silently by the window, Peter entering his apartment to discover a pumpkin bomb on Gwen's bag, the small "SNAP!" sound effect readers may initially miss on a first read if they're too elated by Peter's web catching Gwen.

All these elements are integrated to create the whole issue, which really is only half a story. As I mentioned in the introduction, I believe this narrative is important enough to dissect across two blogs, so in the next post, we'll be examining the fulfillment of Spidey's promise in this issue's final panel. Gwen is gone, the Goblin's giggling. When Uncle Ben was killed, Spidey swore to capture his killer. He promises a different fate for the Goblin here. Discerning readers know where we're going next, but for the moment, let's sit in the loss, allow it to linger. Put yourself with the man in the red-and-blue costume atop the George Washington Bridge and the second death which has rocked his costumed career, his entire life.