Distinguished Critique: Green Lantern/Green Arrow Review

These classic comics provide clear commentary on problems which plagued the 70s...and still impact our world today

—by Nathan on August 31, 2024—

I have not explored the pre-Crisis on Infinite Earths DC Universe to the same extent I've examined the post-Crisis DC Universe (and even there, I have so much more digging to do). But I have become somewhat more curious about the pre-Crisis state of DC–what stories are critically acclaimed? What runs or creators are notable? How does the pre-Crisis version of Batman found in a series like Untold Legend compare to Frank Miller's version in "Year One"? Crisis on Infinite Earths is a demarcation line for readers, forming a historical barrier between two eras of narratives.

The 1970s, a decade I've explored very little of in comparison to the 1980s (or even the 1990s), are a turning point in comics. Much like Crisis separates two distinct periods in DC Comics history, so do the 70s mark a transition period. Though much of the darker, grittier, more mature notions of graphic storytelling were developed through stories produced in the 80s such as Maus, Watchmen, "Kraven’s Last Hunt," and The Dark Knight Returns, the switch from the "Silver Age" to the "Bronze Age" is generally grounded in the 70s. The exact moment Silver became Bronze is unknown. Some note Jack Kirby's defection from Marvel to DC. Others note the death of a certain blond-haired girlfriend in Amazing Spider-Man #121. Still more point to the run I'm discussing today: Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams' Green Lantern/Green Arrow. Two mostly monochromatic heroes, developed here by creators whose level of professional experience decidedly did not match the colors of their selected protagonists.

Green Lantern/Green Arrow

Writers: Dennis O'Neil, Elliot S. Maggin

Penciler: Neal Adams

Inkers: Frank Giacoia, Dan Adkins, Dick Giordano, Mike Pepe, Bernie Wrightson, Neal Adams

Colorist: Cory Adams

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: Green Lantern #76-87, #89, and material from The Flash #217-219, The Flash #226

Publication Dates: April 1970, June 1970, July 1970, September 1970, October 1970, December 1970, March 1971, May 1971, July 1971, August 1971, October 1971, January 1972, April 1972, September 1972, November 1972, January 1973

Politics and social commentary in mainstream superhero comics is not a new thing. In envisioning these worlds of superheroes and vigilantes, writers and artists place them in situations very similar to ours, with real events inspiring grand narratives to peer deep into the heart of human nature. Decades before Nick Spencer commented on current American politics by creating a "Hail Hydra!"-ing Captain America, Steve Rogers was knocking old Hitler's block off. The Fantastic Four gained their powers in a space flight meant to beat the Soviet Union to reaches beyond our world; a Soviet spy was initially responsible for Doctor Bruce Banner's transformation into the Hulk; the X-Men were meant to be an allegory for racism and faced their own robot persecutors early in their costumed careers. Perhaps some of those issues were a little more black and white–Hitler was clearly a bad guy, as were the Soviets–but it wouldn't long for a little complexity to pop up in these four-color fabrications…nor would it take long for writers and artists to start discerning that evil, corruption, and conflict existed within America's borders as much as it existed outside.

O'Neil and Adams' Green Lantern/Green Arrow is as socially conscious as they come, beating Marvel's famous admonishment against alcoholism, the "Demon in a Bottle" story arc in Iron Man, by nearly a decade. The same year Marvel published a controversial indictment of drug addiction at the behest of the U.S. government (which I'll discuss in my next post), DC produced its own popular push against the illegal drug trade. But Green Lantern/Green Arrow tackled a whole assortment of heavy topics–drugs, racism, overpopulation, religious fanaticism–by pairing two seemingly unlikely characters. The choice to bring Hal Jordan and Oliver Queen together is somewhat of an odd one at first glance–they both wear green and pin the color at the front of their superhero monikers, so what?–until you watch O'Neil and Adams dive into the nitty-gritty.

Jordan's Green Lantern is the more conservative of the two; as a galactic "cop," Jordan is often guided by the whims of the Guardians of the Universe; he begins the volume believing them largely infallible in their judgment and wisdom, a notion quickly challenged by the more liberal Green Arrow. Having lost a good chunk of his fortune, the once filthy rich Ollie Queen now lives among regular folk and has become a champion of their causes. He sees the downtrodden, the abused, the marginalized, pointedly arguing with Jordan that those in charge shouldn't be followed blindly and uncovering corruption hiding behind seemingly noble intentions and institutions.

We're given, largely, a series of single-issue stories, with some larger set dressings holding a few of the chapters together. But issues are generally presented as standalone, with different focuses that our heroes must address and/or attack. Lantern's perspective of a rich landlord is shaken when Arrow points out his greedy schemes; Arrow leads a band of Native Americans in a violent rebellion against white landowners, a bitter battle broken up by a Green Lantern offering a diplomatic, legal solution. You often feel O'Neil sides more strongly with Green Arrow's perspective, as it's Jordan who undergoes a genuine crisis of conscience. If anything, Oliver is presented as occasionally too fanatical, with Jordan's more logical approach to their dilemmas providing the cooling level-headed-ness the bowman lacks.

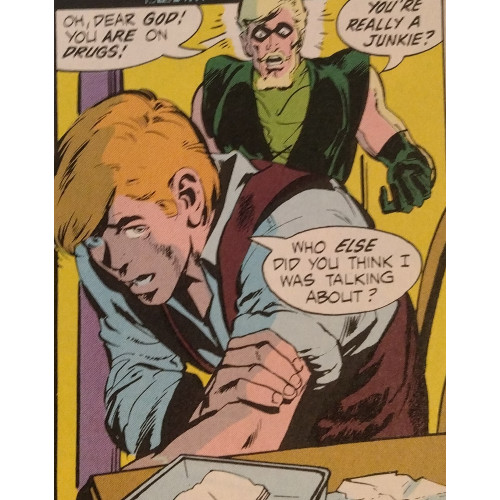

These are relatively blunt narratives, wearing their intentions proudly. It's difficult to fault them for doing so. You're not going to look at a narrative where Arrow discovers his ward Speedy doing drugs and wish he'd condone the poor boy for sticking needles into his arm. The rightness or wrongness of the actions taken by most individuals here is fairly transparent. Occasionally, O'Neil and Adams veer into parable territory–an alien planet suffering from overpopulation is clearly meant to mirror our world, and another issue where a Guardian of the Universe is subjected to a kangaroo court plucks out themes of judicial corruption and justice. Perhaps some of that bluntness would be chastised today–the first appearance of John Stewart brings another African American superhero to a genre inhabited by limited representation, but some of his dialogue choices reminded me of when white writers tried writing Luke Cage. These days, how would readers react to 1970 John Stewart?

Where we find complexity is how our central characters react to the clear evil happening in their world. Using an above example, should the reader side with Green Arrow for leading a band of Native Americans in physical, violent rebellion? Or do we fix faith in Green Lantern's tactic, working within the system? O'Neil and Adams openly oppose drug addiction, but they reach towards the heart behind Speedy's drug use: he's coping with feeling Oliver abandoned him and asks his mentor to become a better, wiser man. There is no one solution the writer/artist team peddle, as there is no one problem they sink their teeth deep into. But they don't stop with the surface problem. Racism, drug addiction, gender equality won't be fixed in a day, nor can they be fixed by waving a power ring around. Perhaps Green Lantern and Green Arrow aren't meant to fix the deeper problems they encounter, at least not the endemic versions of the issues they face. But perhaps Green Arrow can keep a proud fat cat from kicking folks out their homes, maybe Green Lantern can capture a peddler pushing poison to youth.

The two are a regular Odd Couple, in both perspectives and powers. The stories contained in these issues are fairly grounded, including an arc where the duo, joined by a Guardian of the Universe, journey across America to see all her shades of beauty and brokenness. But cosmic powers and alien planets are thrown in for good measure, meaning O'Neil and Adams must temper their characters. When faced with rabble-rousers and gunsels, Green Lantern cannot always rely on his ring; when faced with aliens, Green Arrow must use his wits and fists where advanced technology and sheer power elude him. Thus, a fairly decent balance is brought to our characters–Green Lantern is powerful but not overwhelmingly so, nor is Green Arrow completely ineffectual because he's just a dude with a bow. Perhaps my only complaint is the number of times Hal is rendered helpless because he and Ollie encounter something yellow, his ring's one weakness. The color's appearances seem almost too coincidental at moments.

As he has proven to me in the pages of X-Men and Detective Comics, Adams carries any comic he's ever illustrated. He crafts wonderful moments, singular expressions and seconds frozen in individual panels. In one story, Green Arrow is struck by an arrow, his horror matching ours at the sight of a bolt in his shoulder; a full page contrasts two white figures against a backdrop of psychedelic color to represent a drug overdose; a few largely wordless sequences, such as Hal saving a man from a burning building, call to mind similar tricks Adams used in X-Men around the same time as these issues were produced. His work is highly detailed and wonderfully inventive, pushing how a comic looks and how narrative storytelling can be visualized in a way which draws the eye and stirs the heart.

In the wake of Crisis, both Green Lantern and Green Arrow were changed. Green Arrow ditched the Robin Hood getup beginning with Mike Grell's Longbow Hunters limited series, though he retained his memories of Speedy's drug addiction. Green Lantern was depicted as being susceptible to alcohol's influence, and though I don't know how much of these pre-Crisis tales remained canonical after the Anti-Monitor attempted to destroy the multiverse, it does seem Jordan's straight-laced, law-abiding citizen makeup was altered. The hard truths of reality permeate those stories too, so despite the changes, we can perhaps thank O'Neil and Adams for adding a helping of the grounded and gritty to the life of our space cop and his arrow-aiming ally, a theme which continues playing within the heartstrings of our heroes, in the post-Crisis world and through today.