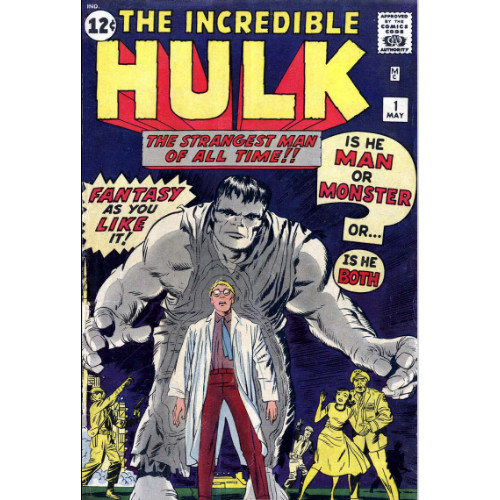

Incredible Issues: The Incredible Hulk #1 Review

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's classic monster is revealed in this issue, redefining the core concept of a hero

—by Nathan on March 10, 2024—

After the fantastic, but before the amazing, there came the incredible.

In late 1961, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby kicked off Marvel's Silver Age legacy with the creation of the Fantastic Four, a team of superheroes meant to rival DC Comic's Justice League. Formidable yet flawed, the Four are often referred to as "Marvel's First Family," indicating how Lee and Kirby successfully intertwined their superhuman feats with complex characterization. They were people first, in and out of costume…heck, when they first appeared, they didn't even have costumes!

Lee and Kirby followed up the Four with the invention of a different kind of hero: the monster. Yeah, a craggy, traffic cone-colored creature lumbered through Fantastic Four, but the Thing was a monster who knew he had been human, who knew he wanted to be human again, who had the support of a surrogate family to ease the frustrations of his transformation. He was a hero who just looked monstrous. With the Hulk, Lee and Kirby devised a behemoth which was a blend of Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the golem of Jewish mythology. The Thing wasn't your standard superhero because he didn't look like your standard superhero; the Hulk wasn't your standard superhero because he didn't behave like your standard superhero.

As I recently dove into the origins of the Fantastic Four in their first issue, I thought I would do the same for the Hulk. As noted in my first FF post, I want to follow these series along periodically, explore these early issues as I allow myself time, engage with the characters and stories, and observe how the legends of our modern mythology sprang from their humble beginnings.

"The Hulk"

Writer: Stan Lee

Penciler: Jack Kirby

Inker: Paul Reinman

Colorist: Stan Goldberg

Letterer: Artie Simek

Issue: The Incredible Hulk #1

Issue Publication Date: May 1962

As I briefly noted in a completely different review, later writers such as Bill Mantlo and Peter David would construct additional complexity around the Hulk, indicating that the bomb which belted Dr. Bruce Banner with gamma rays gave tangible form to a darker personality already existing within Bruce rather than causing a physiological transformation. The Hulk became a deeper representation of Bruce's personality, the parts of him you'd expect a mild-mannered scientist (who some would refer to as a "milksop") to keep concealed. The Hulk is Bruce's id, a manifestation of the primal, reactionary pieces of himself kept beneath the surface.

Though history would allow for greater analysis of the Hulk's personality, Lee and Kirby do a fairly decent job crafting the dual halves of the character in his first appearance. Circumstantial irony becomes their best friend, with examples littered throughout the issue best seen on a second read. Suddenly, through this lens, you begin to contrast the brilliant Bruce Banner with the savage, infantile Hulk; you recognize the grim humor of Banner telling scientist Igor how he "detest[s] men who think with their fists" (made all the more ironic when the Hulk later smacks Igor around); you witness the blustering General Thaddeus "Thunderbolt" Ross demand Bruce to man up, not yet knowing the scientist will smash through a cluster of his soldiers after the gamma bomb accident. In Bruce's transformation, we find a man taken to the extreme opposite end of himself–his brilliance dulled, his precision and care diluted, his humanity forsaken. He's become an apex of masculine strength, the kind of sheer power General Ross would undoubtedly appreciate, yet his loss of intellect and humanity renders him a monstrous threat rather than a superior soldier.

The Hulk is not a hero. It may be the most shocking aspect of the book, but you see this (as I've noted elsewhere) time and again with Lee's heroes. Except for the Fantastic Four, they don't necessarily react to their new circumstances with a sudden desire for altruism. Spidey decides to make money off his powers. Daredevil avenges his father. The X-Men seek self-preservation. And the Hulk just smashes his way out of his confinement and lumbers across the desert. "The world is mine!" he tells Rick before suggesting he's going to kill the young man. Elsewhere, he bats Rick aside, smashes a jeep, and basically insults humanity any chance he gets. We're puny insects, fools, weaklings.

His motivations aren't necessarily defined; he's not quite at the "Hulk just wants to be left alone!" stage and manages to exhibit some level of intelligible dialogue (maybe turning green saps the rest of his intelligence?). He's a lumbering wanderer, almost like a drunk looking to pick a fight with anyone. He has power, and he's going to use that power for himself, and heaven help anybody who ends up in his way.

Lee and Kirby do seem to recognize the problem with the premise: though the idea creates a compelling central character (we're supposed to root for the monster who hates humanity?), there's only so much material you can take from "monster moves from one fight to another." The creators have to give the Hulk an adversary, and to do so, they toss the Gray Goliath into the midst of Cold War conflict by introducing the Gargoyle. Like the Mole Man represents a twist on the Fantastic Four (an individual subjected to life-altering circumstances who embraces selfishness over humanitarianism), the Gargoyle, much like the Hulk, is a physical monster, yet he retains the grand brainpower the Hulk has lost. He is driven, we're initially led to believe, by power, viewing the Hulk as a threat to the power and fear he's accumulated as a superhumanly intelligent terror in the Soviet Union.

Yet the Gargoyle's threat is minimized when we reach the issue's climactic moment. Lee and Kirby do this purposefully, and I'll dig into the notion in a moment, but once Bruce and Rock Jones stand before the Gargoyle as his captives, the villain begs for the genius scientist to restore his humanity. The twist could be used well, to showcase a deeper humanity underneath the skin of, as we're told, "the most feared man in all of Asia!" But this is the first instance we're shown where the Gargoyle despises his condition, and though it's meant to draw further comparison between himself and Bruce Banner, the shift is a sudden departure from the villain's previously stated motivations. We're not made to sympathize with him any moment before this one, and I would argue the twist falters for this reason.

Where the moment succeeds is dramatizing who the real hero of the issue is: Bruce Banner. He resolves the conflict with the Gargoyle, not through dramatically smashing his foe, but through the application of his genius. It isn't fair to say the Hulk gets Bruce into the troubling situation on the other side of the Iron Curtain, but we can note Bruce provides a solution the Hulk would be incapable of supplying. Lee and Kirby display Bruce's heroism even prior to the transformation, when Bruce rescues Rick Jones from the gamma bomb which irradiates the scientist. Not bad for a milksop. An undercurrent of selflessness, contrary to the Hulk's singular, selfish method of thinking, continues to contrast the two and heightens the tragedy of Bruce's unfortunate circumstances.

Through this issue, Lee and Kirby again utilize circumstantial irony to undercut the conventions of the superhero genre. With Bruce Banner and the Hulk, you don't have the same duality found in characters such as Spider-Man, Daredevil, the X-Men, Superman, and Batman, who keep their superhuman careers separate from their regular lives through costumes, masks, and monikers. They're always the same person, just maintaining two distinct lifestyles (and, generally, exhibiting a few distinct character traits depending on which side is "driving"). The Fantastic Four, from essentially the start, do not maintain their secret identities, and though they wear the costumes and use codenames, establishing uniformity between their heroic and human ventures.

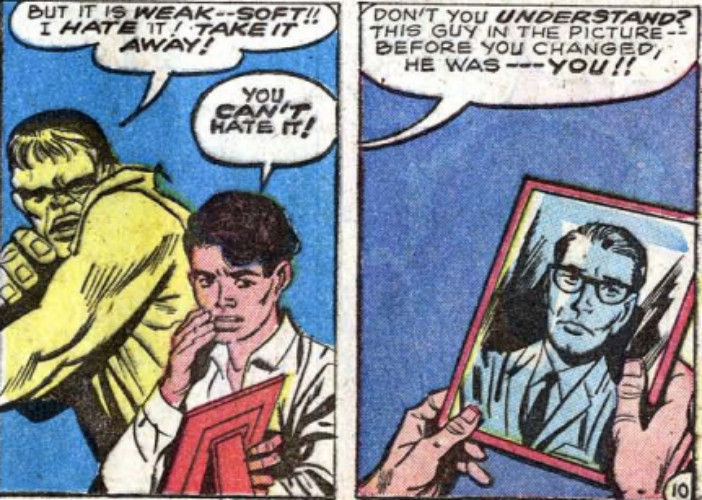

The Hulk is a different beast. Bruce Banner fears the transformation, and the Hulk scorns the idea of becoming Bruce Banner. "Human?" he roars at one point. "Why should I want to be human?" In these early issues, the transformation is triggered by time. Bruce has no choice whether he becomes the Hulk, just like the Hulk has no choice whether he reverts back to Bruce. There's no costume to remove. The Hulk and Bruce are eternally intertwined, creating an integral symbiosis which goes beyond acquiring superpowers or adopting a new name.

I should take a moment to discuss the issue's supporting cast. Much like with the introduction of integral characters such as Aunt May, J. Jonah Jameson, and Betty Brant early in Spidey's career, Lee creates cast members who stay for the long haul. Betty Ross, Thaddeus Ross, and Rick Jones round out the named characters introduced here. Betty is not quite a love interest just yet, but Lee and Kirby hint at the direction, and though Lee's treatment of her isn't terribly gentle (Ross cuts off her during a conversation about "man talk," and Bruce later rushes her out the door), there's at least no infamous "love triangle" (yet). Betty offers a counterpoint to her father, respecting, even admiring, Bruce for his gentler nature and his intelligence. We're given hints toward a developing interest, with some indication a little hiccup called "the Hulk" will prevent the freer development of a relationship between the two, much like the specter of Spider-Man dangles over Peter Parker and Betty Brant.

Ross is an antagonist on a level similar to J. Jonah Jameson, a non-powered, mustachioed individual in a place of authority and influence with a hatred for a superhuman while failing to note his connection to that superman’s alter ego. Lee develops better tension between Ross and the Hulk than he does initially for Jameson and Spider-Man–Ross has decent motives for wanting to hunt a monster who thrashed his soldiers, and that motivation is inflamed into rage when the Hulk terrifies Betty. Rick is the series' "everyman" character, indebted to Bruce after the scientist saves his life and tagging along to provide commentary, particularly in the moments where the Jolly Gray Giant takes leave of his senses. Rick is sorta dumb at moments (yes, even after accepting a dare to drive into the middle of a gamma bomb test site), and his attempts at being clever risk tipping off the military to Bruce's connection to the Hulk. But he's a kid. Whaddayagonnado?

The Hulk's introduction doesn’t quite possess the same philosophical quandaries posed by Spidey's origin—in fact, Peter's decision to use his abilities for good as a result of his own selfishness is contrasted by Bruce's life being turned upside down through a selfless action. Lee and Kirby do strike an equally tragic chord here, if not for different reasons. Bruce's inability to control his transformation and the fear which results from him becoming a monster of a man makes for a uniquely different central character, someone who can't as easily hide his other half. Similar to some of Lee's other creations, the Hulk is not naturally disposed to being a hero–perhaps even more so than some of Lee's rational protagonists–yet despite his general hatred towards humanity, he'll find himself drawn constantly back to protecting them. He'll become an Avenger…for a moment. He'll become a Defender…for a moment. He doesn't quite fall into that clean villain/hero category. But what were we to expect from a comic where the cover of the very first issue asks, "Is he man or monster or…is he both?"