Distinguished Critique: Batman: Ego and Other Tails Review

This volume presents several examples of a master craftsman's calculated contributions to Gotham City

—by Nathan on February 4, 2024—

I have memories which I have filed away under a mental folder called "early comic reading experiences." They're bundled together fairly tight so that, often, when I select one, I tend to pull a few others with it. I've touched on these before: images, fairly vague, consisting of a place and a comic I was reading. Sitting on the edge of a soccer field where I first read Jeff Smith's Bone or in the backseat of a car zooming down a highway heading into Chicago where I flipped through Kurt Busiek's Marvels. A few weird books have gotten themselves stuffed into that folder–John Gallagher's Buzzboy comes to mind, as does a Mr. Majestic volume I believe was written by Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning–only coming to mind because of their proximity to other stories. I just read back in those days, y'know? I didn't really pay attention to who was writing or who was penciling or if I was reading Part 6 of a massive summer crossover.

Mixed in with the other files is one labeled "DC: The New Frontier." It's the late Darwyn Cooke's magnum opus, a love letter to the early years of DC Comics. I read it years before I ever knew who the Challengers of the Unknown or Wildcat or Alan Scott were. I probably struggled through a host of characters I was unfamiliar with, trusting in the known (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman) to guide me through an era along whose surface I had scraped the smallest of fingernails.

I don't know why I filed New Frontier away in my brain when other stories went forgotten. I don't remember its impression on me. Reading it again a few years back, I was better prepared to dive into Cooke's colorful world of Cold War-era superheroes, a callback to the halcyon days of costumed characters, before universe-ending crises and an abundance of multiverses. New Frontier is simple, focusing on its heroes and how many of these DC characters first collaborated.

I've since checked out Cooke's take on Superman through the Superman Confidential story arc "Kryptonite," which paired Cooke with Tim Sale, another storyteller gone far too soon. Centered on Supes' earliest days, "Kryptonite" is a nice affirmation of who the hero is as he strives to define his strengths in the face of new weaknesses.

It shouldn't come as a surprise, given Cooke’s predilection towards embracing the beating hearts of his heroes, that Batman: Ego (along with a few other stories) perfectly (and, in one case, "purrfectly") capture the soul (if not the ego) of Gotham's Dark Knight Detective and a few of the city's other dressed-up denizens.

Batman: Ego & Other Tails

Writers: Darwyn Cooke, Paul Grist

Pencilers: Darwyn Cooke, Bill Wray, Tim Sale

Inkers: Darwyn Cooke, Bill Wray, Tim Sale

Colorists: Darwyn Cooke, Matt Hollingsworth, Dave Stewart

Letterers: Jon Babcock, Darwyn Cooke, Richard Starkings

Issues: Batman: Ego one-shot, Catwoman: Selina’s Big Score one-shot, and material from Batman: Gotham Knights #23, Batman: Gotham Knights #33, Solo #1, and Solo #5

Publication Dates: October 2000, January 2002, September 2002, December 2004, August 2005

When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby dropped a bomb on scientist Bruce Banner, flooding him with the radiation that turned him into the Hulk, there was nothing psychological about the transformation. The change was purely physical, Banner growing larger and turning gray, then green, tearing his shirts and shoes and socks, and talking like a two-year-old. It was only years later that writers such as Bill Mantlo and Peter David began applying a more analytical lens to the Hulk, wondering if the monosyllabic monstrosity was a manifestation of Banner's repressed emotions and rage. In other words, the gamma bomb did not create the Hulk, it merely unleashed what was already within the milksop of a scientist.

When Bill Finger and Bob Kane had Bruce Wayne's parents shot in a Gotham City alleyway and made the young man swear to fight crime in their name, I assume they didn't consider the boy's mental state too deeply. A kid who grows up, dresses like a bat, and punches clowns in the face sounds pretty cool through one lens. Through another, it sounds more than a tad concerning. Again, years passed before creators like Frank Miller really dove into the mind of Batman and gave his decisions the weight they deserved. What does it say about someone who dresses like a bat and punches clowns in the face? If you're Darwyn Cooke, you create the argument that the Waynes' murder did not create Batman, it merely unleashed what was already within their young son.

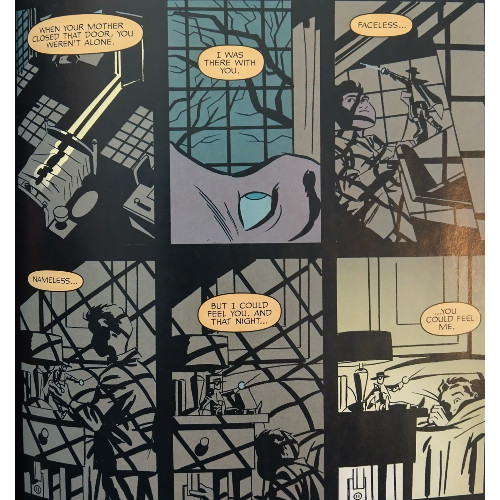

Batman: Ego begins relatively early in Batman's career (where, I'm assuming, stories such as "Year One" and "Year Two" were still considered canonical), and after one particularly defeating evening, a distraught Bruce finds himself in the depths of the Bat-Cave, questioning his future. And, in the depths of his cavernous mind, he embarks on some very real soul-searching in a Christmas Carol-style haunting, as the ghost of Batman torments his dreams. The sequences and conflict crafted between the spectral vigilante and the very human Bruce evoke Cooke's thesis on the character: that Bruce and Batman are inseparable, that Batman represents something deeper than just a mask Bruce puts on each night.

The question about "Is Bruce Wayne Batman or is Batman Bruce Wayne?" is not a new inquiry to ponder and has often served as the focus for analyzing the character. It's the foundation for why Bruce chooses to consistently sacrifice himself for his city, an answer which goes deeper than "to avenge his parents," "to keep people safe," or even "to make sure no child has to suffer the same fate as Bruce did." Those reasons are belayed by the concept that this lifestyle of crime-fighting is part of Bruce's DNA. Yes, he wears a mask and a costume and uses a different name, but as Cooke sees it, there is no difference between the two. To abandon Batman would be to abandon Bruce Wayne, a form of identity suicide.

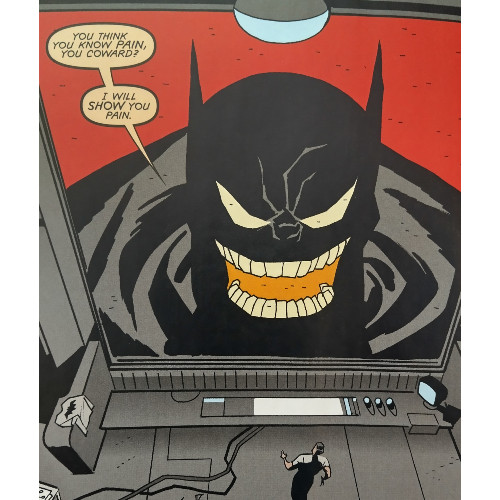

Likewise, Cooke argues, Bruce can't just compartmentalize Batman. He can't wake up each day and attend board meetings, date women, and host fundraising events until the darkest hours of the night, when he can finally wear the cape and cowl. No, the two are intertwined, and though Bruce believes this places a twisted constraint on his life–won't he ever find peace or be freed from this mad, nightly routine?–he also concedes that his human identity provides a balance. Batman, as Cooke determines, is Bruce's fear, the personification of the horrors Bruce encountered from even before his parents' murders. Their deaths were just the catalyst for Bruce to finally channel his fear, which the human side of Bruce staunches. Cooke implies that, were Bruce to give more fully into this darker side of himself, the Batman would be a calculated killer, finally putting an end to monsters like the Joker. So while Batman provides the vehicle for Bruce to channel his terror, Bruce must remain in the driver seat, providing the empathy and humanity necessary to keep his emotions and turmoil from crossing lines which could never be uncrossed.

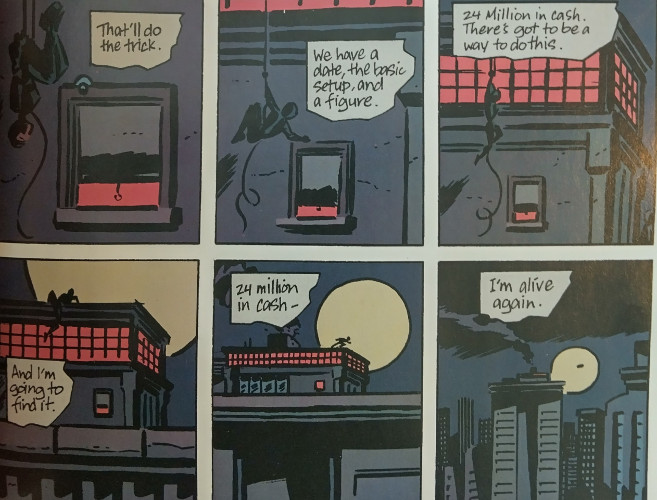

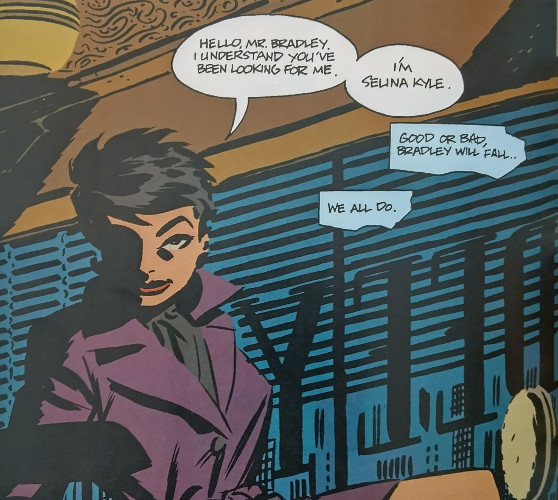

Catwoman, too, receives a deep dive courtesy of Cooke in her own drama. Selina's Big Score is an unabashed heist comic in the vein of Ocean's Eleven, with the feline queen of crime scheming a massive robbery. Cooke finds a dramatic balance between the planning, action, and characterization, wisely divorcing Selina (for the most part) from her friends/enemies/significant others relationship with Batman. Save a few scant references, the Dark Knight is little seen here, allowing Selina the room to grow without being dependent on him.

I often view Selina Kyle the same way I view Elektra or Felicia Hardy: she is, foremost, a receptacle for romantic tension. She's the fly in the ointment, the wrench thrown into the gears of Batman's life to give him some emotional torment. By removing Bruce from the narrative, Cooke establishes that this is purely a Catwoman narrative, with little to do with the relationship which has made her so infamous. Selina can be driven by other motivations and relationships, Cooke asserts.

Cooke doesn't necessarily portray Selina as the "thief with a heart of gold," as her intentions are fairly selfish. Loyal to a fault to some people, highly distrustful of others, Cooke's Catwoman is a complex figure who must juggle her personal aspirations while facing the consequences of her own actions. Can she trust people she's betrayed in the past? Can she place people in harm's way for her own profit? Selina here is an impeccable actress, toying with even the reader. Cooke nicely uses scenes of plotting and planning to craft relationships and offer nods towards characterization, visually teasing the reader with the construction of a massive scheme while weaving in smaller, heartfelt moments you must watch for.

Smaller tales can be found between the bigger events in the volume, offering additional examples of Cooke's ability to display core character qualities. One short story sees Batman descend upon thugs who murder a young boy's parents, silently incapacitating each crook as a terrifying wraith. The parallels between Bruce and the boy go unspoken, save for the title ("Deja vu"), leaving the reader to soak in the reason for Bruce's wordless vengeance upon these men, a far more powerful sentiment than if Cooke made the Caped Crusader voice his displeasure. A fun tale envisions a "date night" between Catwoman and Batman as our hero chases the thief across Gotham City, Cooke's humorous dialogue highlighting the hilarity of the "relationship" between the Bat and the Cat. There's not much depth to be found here, necessarily, but the playful narrative moves well, Tim Sale's vibrant characters constantly in motion to provide the story's efficient pacing. A hint of melancholy is found here, admittedly, knowing neither creator is with us any longer. I don't know if Cooke and Sale collaborated beyond this short story and the "Kryptonite" narrative; if I ever learn of others, I'll be certain to snatch them up.

Ego can, on occasion, feel a tad overwrought, with Cooke placing emphasis on so many pieces of Batman lore that he occasionally becomes entangled in a web of crisscrossing concepts. There’s a reason why A Christmas Carol is so neatly divided into the past, present, and future instead of gorging the reader with all three at once…though given Sale had illustrated a Jeph Loeb-written Halloween special toying with that idea a few years earlier, I can see where Cooke would have wished to avoid any comparison. The smaller stories are more streamlined efforts at engaging with important aspects of Batman's personality, whether having fun with his unorthodox relationship with Catwoman or showcasing his efforts to avenge anyone who suffered like he did.

Darwyn Cooke provided a unique voice and style in the graphic medium, and readers would be wise to not let the cartoon-inspired palette he used on New Frontier and other DC stories to undermine his love for the characters he presented. This volume should offer readers new glimpses into the minds of a few of Gotham's most celebrated citizens, whether through the dream-derived philosophizing of a weary vigilante or the intricately woven plotting of feline felon intricately woven herself by a creator whose un-produced joys are lost to us. All the more reason to pause and soak in this collection as it was intended to be.