Distinguished Critique: Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters Review

Occasionally heavy-handed, Longbow Hunters successfully reintroduces Green Arrow to the post-Crisis DC landscape

—by Nathan on November 16, 2023—

You’re running down a street after a successful bank heist, bag of greenbacks in one hand, gun in the other. Sirens slice through the air, but you don’t see any red-and-blues just yet. Home free. Maybe the cops are following the other guys.

Gasping for air, you take a sharp turn, down a dimly-lit alley when–bam!–outta nowhere, you’re sucker punched in the chest and take a spill, your remaining breath gone. You fall back, thudding on the pavement. Gun clatters to the ground, bag drops. As your vision clears, you spy an object on the ground next to you. It’s an arrow…attached to a boxing glove? You’ve been punched in the gut with an arrow? The archer who fired it, some blond dork cosplaying Robin Hood, steps out of the shadows and mutters something about truth and justice. You’re bewildered. Yeah. You’ve been punched in the gut with an arrow.

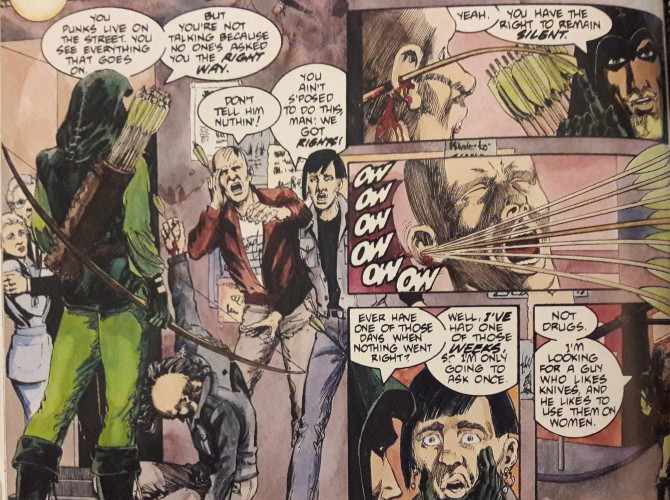

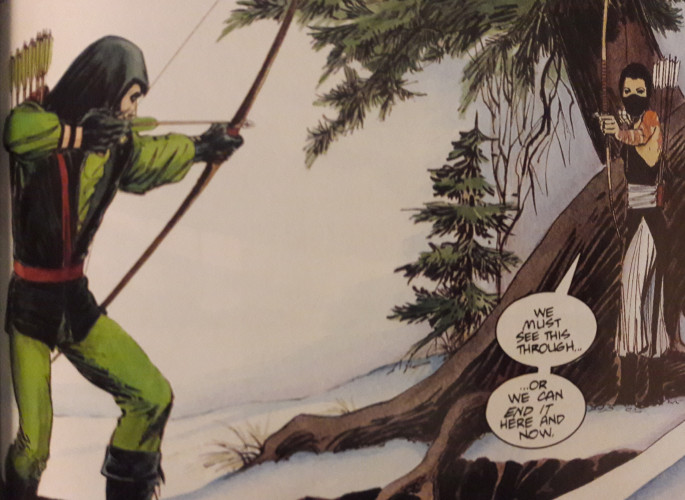

Now a new scenario, similar to the first. Fast forward through the running, the sirens, the panting, the turning. But you’re not knocked for a loop. This time, a silver arrowhead finds a home in your knee. The bag and gun drop, like before, but you sprawl on your face, screaming, the pavement muffling your cries. The archer steps into the light, like before, but he no longer looks like a reject from a Renaissance fair. A green hood and mask obscure his facial features as he nocks another arrow. The message is clear: give up, or the next one’s going through your head.

Who is this verdant vigilante? And why isn’t he silly anymore?

Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters

Writer: Mike Grell

Pencilers: Mike Grell, Lurene Haines

Inkers: Mike Grell, Lurene Haines

Colorist: Julia Lacquement

Letterers: Ken Bruzenak

Issues: Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters #1-3

Publication Dates: August-October 1987

I know very little about Green Arrow as a character. I’ve never watched the Arrow television series, nor have I indulged in many comics. I know a bit of his history–his origin, his death, his resurrection–and own a volume collecting his adventures with Green Lantern, which I hope to read and review sometime down the line. Otherwise, I’m oblivious.

I would have expected this series to be an updated origin, Longbow Hunters being Oliver Queen’s first major post-Crisis on Infinite Earths narrative, though research indicates Grell later retold Ollie’s origin during an ongoing Green Arrow series he scripted. If anything, Longbow Hunters appears to be a reintroduction to the bowman in a post-Crisis setting, his personality a far cry from the guy who slung boxing glove arrows or other gimmicky trick quarrels.

I’ve garnered interest, recently, in these post-Crisis narratives, wondering what the appropriate "jumping on" points for different characters may have been for fans. In certain cases, such as Frank Miller’s "Batman: Year One" or John Byrne’s Man of Steel limited series, that place seems to have been the beginning, radically redefined origins for characters. In other instances, such as this series, it appears to have been a rebranding, transforming the character for audiences old and new.

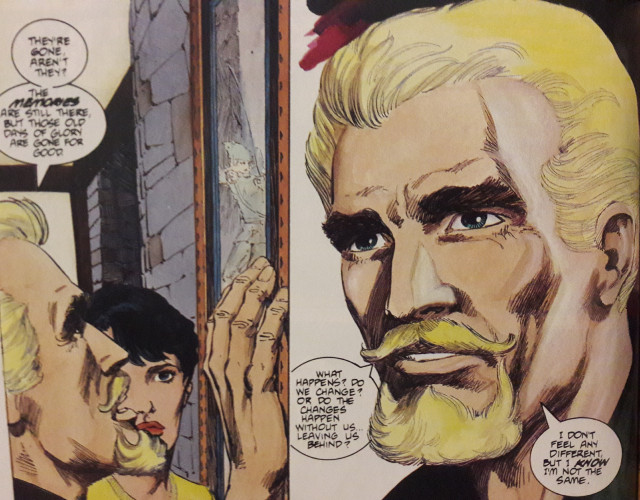

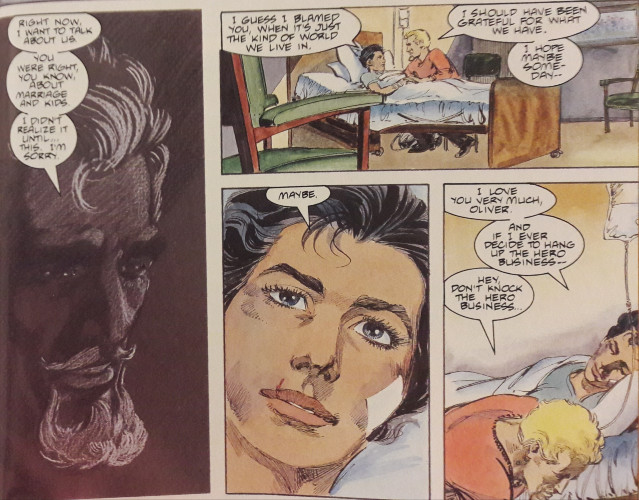

And speaking of old, one of Grell’s major changes to the character is that Ollie’s feeling his age and, with it, a dwindling sense of purpose. An extended sequence sees him bemoaning his recent history to girlfriend Dinah Lance, the superheroine Black Canary. "I lost the edge," he tells her, thinking back to "those old days of glory" when life was simpler. Somewhere along the way, he got lost, strayed from his original purpose, hid behind boxing glove arrows and other tricks.

It’s Grell’s mission statement, writ large and feeling somewhat blunt. This old codger has lost some steam in the recent past and needs to find that edge somehow. Grell makes it clear, almost painfully obvious at moments, what exactly he’s trying to do in the context of Ollie’s character. Better commentary can be found when you extract Ollie’s statements and actions from the narrative and apply them more broadly. It’s the late 80s, an era where an aged hero roams the dystopian streets of a grim future Gotham, where Comedians are killed, where women are crippled by clowns, where the devil can be broken by a towering mobster. "Get with the program, Ollie," Grell seems to be saying. "Grow up." Boxing glove arrows ain’t gonna cut it anymore.

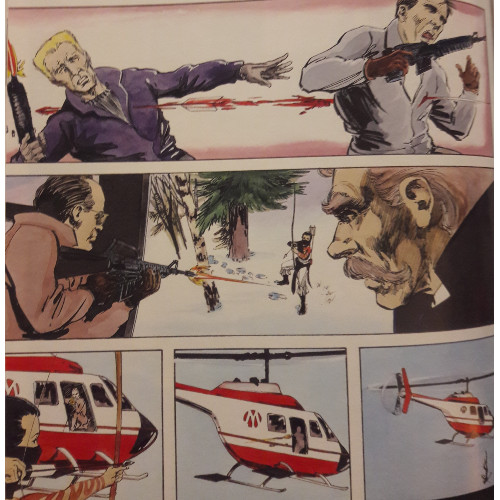

So while Ollie’s pity party feels less sharp than his arrows, other elements of the story roughen the Green Arrow’s edges. Violent murderers stalk the streets, including a serial killer hunting women and a rival archer not afraid to skewer victims like shish kabobs. Ollie himself, through loath to kill, frequently visits injuries upon his adversaries far more impactful and long-lasting than a bop to the kisser. Hands and knees are skewered, and while Ollie draws the line at murder, another archer is less persuaded, her instruments of death piercing chests and faces, downing a helicopter late in the narrative.

Grell, as writer and artist, has secured control over the narrative other creators may not have possessed, giving him freedom to push the boundaries and introduce more mature content. In places, the extreme violence cements his earlier thesis, giving Green Arrow the edge he’d been missing in spades. It’s a clever case of "Be careful what you wish for," and here at least, Grell is sharper with his commentary. Ollie becomes surrounded by death without succumbing to its siren call, his newly introduced female rival offering a counterpoint and showing Ollie the kind of killer he refuses to become. Elsewhere, an unrepentant torture scene attempts a similar analysis, earmarking the kind of criminal Ollie wishes to eradicate. The days of aliens and supervillains with funny names are done. The Green Arrow now faces killers and men with power and money who will stoop to physical abuse to either gain the upper hand or display the cruelty of their seeming security.

I have noted, time and again, comics’ relationship with violence, when and where such gratuities feel appropriate and when and where they feel misplaced. Here, the bloodletting feels mostly in step with the narrative Grell is telling, though the manner by which the torture scene occurs–and to whom the abuse occurs–feel jarring and would likely be decried in a modern context were the story replicated today. The scene in question is not unlike Alan Moore’s Killing Joke, placing a capable individual in the role of victim and requiring they be saved/avenged by a hero who could have been motivated by less barbaric circumstances. In a story where Grell spends many pages indicating to the reader "Look, Green Arrow is edgy now," the scene feels excessive and needless. Ollie putting an arrow through a guy’s hand, or his rival archer skewering a man through the side of the head, was enough to tell me we’re in different territory.

I don’t know if these ideas–Ollie’s edginess or his age–were played up in other stories Grell wrote, but they work well here to redefine the Emerald Archer. Grell, perhaps more than some of his compatriots, is a tad blunt in discussing these changes. John Byrne clearly indicated the time period his Man of Steel series was set in, but these elements are woven in fairly subtly (he shows you Lex Luthor is a Donald Trump analogue without ever telling you Lex Luthor is a Donald Trump analogue); Frank Miller grafted some additional shadows onto Batman and made him brawl with thugs in the street, bringing the vigilante back to basics; Hal Jordan was temporarily made an alcoholic, his characteristic bravado embellished by liquid courage. The writers don’t need to wave their arms or hold up signs, shouting at you they’re making grand changes to these older characters.

Grell’s alterations are welcome–it’s interesting, in a medium composed of eternally young protagonists, to see a superhero gripe about aging, particularly in a mainstream title (as opposed to the concept being relegated to an alternate timeline, such as in The Dark Knight Returns or even Flashpoint, if we’re including the Thomas Wayne version of Batman). Grell allows Ollie to become relatable in a different way than before, especially to an audience who is aging right alongside these characters. It’s just a slight shame he’s a tad too heavy-handed about it at moments.

If you’re willing to work through some of Grell’s blunt commentary, you should find that Longbow Hunters successfully reintroduces Oliver Queen’s green vigilante to the immediate post-Crisis era. Queen’s trying to maneuver this new world, a world where he’s no longer a young man, a world where the thugs and villains may not run around in funny costumes and masks any more. The limited series would kick off Grell’s longer Green Arrow series, so don’t expect every thread to be wrapped up or every idea to be explored in depth. Still, for a three-issue limited series, Longbow Hunters often aims itself straight and true…and if you don’t mind the cliche, hits the target firmly, albeit a little off-center. No bullseye, but close enough.