Random Reviews: Buzzkill

A unique limited series, Buzzkill tackles a very human problem through an unexpected lens...with unexpected results

—by Nathan on September 22, 2024—

There's a story out there about Stan Lee having Amazing Spider-Man #96 printed without the Comics Code Authority's seal of approval as the first chapter of a three-part narrative about drug addiction at the request of the American government. If you're interested in the details of the issue's publication itself and the ramifications, you can find the full story across a bevy of publications–it's a rather important (some might even say "momentous") anecdote in the annals of comic book publication history. What I would like to to note is that, in the aftermath, the Code's stance was loosened on the use of drugs…as long as narcotics were depicted negatively. Abuse, addiction, stuff like that.

The decision, certainly, paved the way for classic stories such as "Demon in a Bottle," depicting Tony Stark's first head-on collision with alcohol, and "Snowbirds Don’t Fly," the Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams' Green Lantern/Green Arrow issue published in the aftermath of Code's changing stance. Stories such as these depict a superhero's struggle with substance abuse and dependency–Tony Stark is still Iron Man, he's just tipsy and a jerk; Speedy is still a bow-slinging sidekick, he's just high.

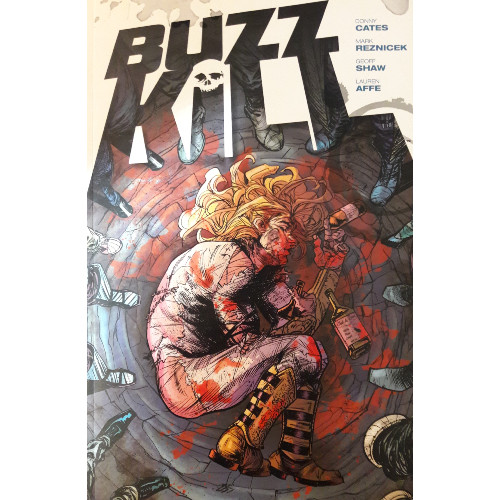

The pre-1971 Comics Code Authority would have had a fit were writers Donny Cates and Mark Reznicek to waltz into the room and pitch their concept for Buzzkill: not only do we have a whole series predicated on the topic of substance abuse, but–get this–our protagonist derives his superpowers from narcotics and alcohol. No spider bites, gamma bombs, or cosmic rays. Just a splash of vodka or Jack Daniels or whatever he has on hand.

A real kick in the head, isn't it?

Buzzkill

Writers: Donny Cates, Mark Reznicek

Penciler: Geoff Shaw

Inker: Geoff Shaw

Colorist: Lauren Affe

Letterer: Lauren Affe

Issues Collected: Buzzkill #1-4

Volume Publication Date: April 2014

Issue Publication Dates: September-December 2013

Publisher: Image Comics

I love "Demon in a Bottle." The Iron Man story I referenced in the introduction is one of my favorite Marvel Comic narratives of the 70s. It's a mature, stirring depiction of a man consumed by an addiction, subtle in its portrayal of Stark's seemingly innocuous inclination to imbibe. You're not meant to realize Stark's alcohol obsession from the start, and even if you're looking for it, David Michelinie and John Romita Jr.'s narrative is unobtrusive enough to not call attention to the addiction until the house of cards Stark's constructed begins to wobble and topple.

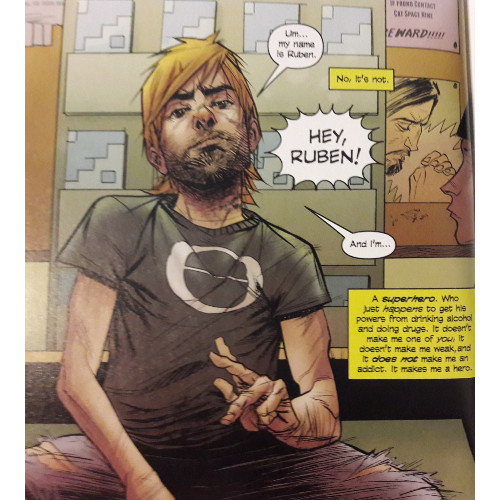

That's not the style we find in Buzzkill. You are, from the jump, aware of what's happening. Subtle doesn't cut it. Our hero, Ruben, abuses drugs and alcohol to gain his crime-fighting abilities yet finds himself susceptible to the effects of irresponsible usage–he's not like Captain America or Wolverine, who can just shrug off the side effects of alcohol. After Ruben realizes he can't remember one particularly devastating battle, he knows his dependency has become a problem, one which needs addressing.

Classic as "Demon in a Bottle" and "Snowbirds Don’t Fly" are, they layer on their respective "drugs are bad, kids" message fairly heavily. Perhaps Michelinie and Romita Jr.'s story is more nuanced in its portrayal–O'Neil and Adams take a more direct approach–but the message is clear by time you reach the end of its penultimate chapter: Tony Stark's alcoholism is a tragedy, working to unravel his reputation as both Iron Man and the head of Stark Enterprises. Buzzkill is, again, obvious in its premise, but it achieves a superior characterization through its portrayal of Ruben.

Ruben's addictions are treated as harmful, but as his dependency is also the source of his powers, extra care must be taken in considering the ramifications. The back cover touts a tagline of sorts: "Drink and Live…Stay Sober and Die." This isn't just a matter of Ruben admitting he has a problem and needing to come completely clean. When a horde of supervillains shows up at his AA meeting, ready to beat the living daylights out of him (and worse), Ruben must question the cost of taking a drag of a cigarette to increase his invulnerability…and whether scrambling away for a sip of wine is worth giving him the juice he needs to take these punks down.

You can argue that Cates and Reznicek write Ruben into a corner–this is a superhero comic, after all. It wouldn't be much fun if our protagonist, despite the consequences of his addictions, laid down and let himself be beaten or killed by his rogues gallery. To some, it may feel like cheating that Ruben is "forced" by the creators to take a swig of alcohol to develop the strength needed to fight a band of enemies.

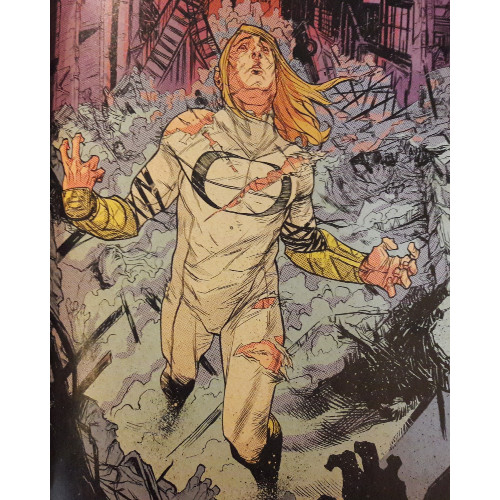

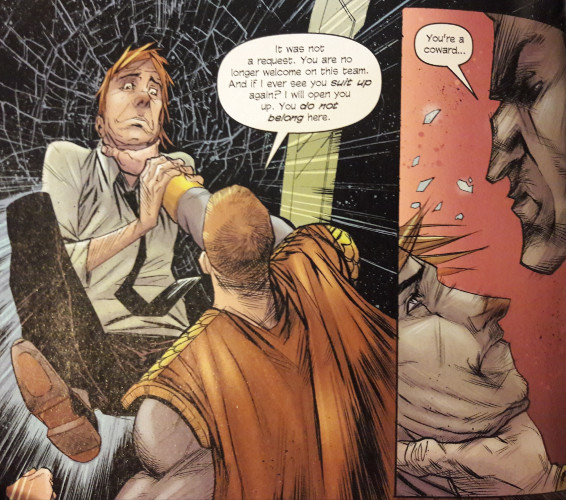

As the story develops, the focus shifts, and the question changes from "Should Ruben drink or smoke at all?" to "Why would Ruben drink or smoke?" At face value, Ruben cutting himself off completely would be the answer to the first question, similar to Stark's solution. But as we get deeper into the tale, we realize Cates and Reznicek are more interested in addressing the struggle that exists, not removing the struggle. It's not an easy road Ruben walks as he battles his demons and addresses the hurts he's caused others. Though we'd certainly enjoy watching old friends and teammates set aside prior transgressions, not everyone addresses Ruben's irresponsible actions with the same grace as others. Trust has been broken. Heartache lingers. Tempers flare. It's the heartbreaking reality Ruben staggers through, and Cates and Reznicek don't shy away from that ache.

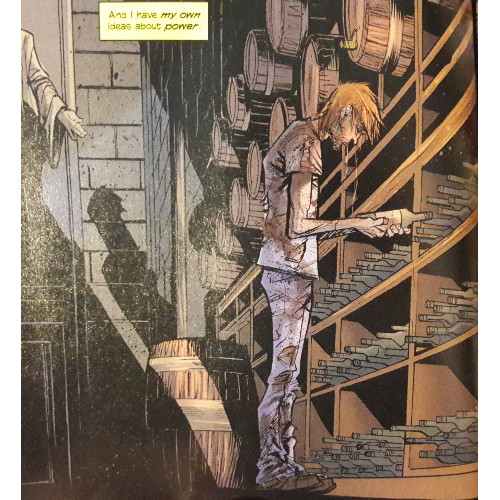

Powerful as the story already is, the creators double the impact by setting up some genuinely engaging twists. I won't get into details, but these developments alter the story powerfully, setting up additional conflict and satisfyingly tying the beginning of the story to its final chapter. I've noted this before, but twists are hard to make work in the comic book medium, either because so many of them have become well-known (such as Gwen Stacy's death), several are more infamous than famous (like Ben Reilly's survival and the subsequent "revelation" that Peter Parker was a clone), or they're later retconned out of existence (like the other "revelation" that Ben was the clone the whole time!). A standalone narrative like Buzzkill, which isn't reliant on its central protagonist's decade-to-decade continuation and relative narrative homogeneity, can toy with the story's fabric, play at the edges.

One of these twists, though surprising, is telegraphed somewhat earlier in the series–it isn't stated directly, but anyone picking up on the hints can start putting two-and-two together perhaps a little earlier than Cates and Reznicek wanted. The development itself ends up being ultimately satisfying, providing answers for lingering questions and bringing a few details seeded earlier to full flower. As the tension builds, your imagination begins asking if Cates and Reznicek are really taking the story in this direction…and when it's revealed that, yes, they are, you can’t help but feel satisfied, even if you're not wholly surprised.

Outside the narrative and its winding path, Cates, Reznicek, and Shaw craft a fully-fledged world that feels lived-in, populated by superheroes with subtly introduced backstories and history. When the aforementioned army of adversaries assemble, you don't feel overwhelmed by the presence of so many villains–you're more intrigued by the notion that Ruben has fought so many super-dudes previously. You can easily believe each villain has beef with him. Likewise, Ruben's conversations with fellow heroes insinuate past relationships and team affiliations we can believe existed before the story began. Various nods are made to pre-existing characters from other companies–Doctor Blaqk is clearly a drugged-out version of Doctor Strange, High Guard feels like a cross between Superman and Captain America, and an armored vigilante named Eric (whose codename no one can keep straight) seems most inspired by a certain Dark Knight Detective. The references are appreciated, adding to the depth of the world our creators invent, bringing a sense of reality and a scope of history, even if it's largely insinuated.

Buzzkill fails to live up to its name, if we take it literally as a narrative design to defeat, deflate, or depress. I encourage curious readers to take a gander; I've been coy about the twists and mum about the ending to this four-issue saga because they deserve to be experienced firsthand. Last year, I reviewed Cates and Shaw's God Country for Geeks Under Grace, discovering a heartfelt story dealing with family trauma and reconciliation. Here, we get a glimpse into a different kind of pain, addiction, and the consequences which follow suit. Set within a fully realized, superhuman landscape with a focus on very human characters, Buzzkill won't harsh your vibe none. If anything, it's too short, opening us to possibilities that would make for a strong ongoing series. At its length, if readers are looking for a good–excuse the expression–binge read, you won't be disappointed.