Random Reviews: Huck (Book 1): All-American

Huck rises above the darkness of modern superhero comics to become a shining star of kindness and compassion

—by Nathan on September 17, 2023—

As I noted in my review of Superman: Birthright, writer Mark Waid, famous for not only the early 2000s update of the Last Son of Krypton’s origin but also Kingdom Come with Alex Ross, was highly, highly displeased (and that may be putting it lightly) with Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel, particularly the moment where Superman breaks Zod’s neck. He was not the only comics writer named "Mark" frustrated with the film’s polarizing dark take on Clark Kent’s alter ego. Scottish writer Mark Millar similarly expressed his disappointment in Man of Steel, stating he was traumatized by the film and indicating the movie as mounting evidence of the ever-darkening horizon of the once colorful, upbeat superhero genre of comics.

When the guy who wrote hyper violent, serious, and gritty series like Old Man Logan, The Ultimates, Civil War, Kingsman: The Secret Service, and Nemesis tells you your stuff is too dark…maybe that’s time to shut up and listen.

In response to the Henry Cavil-led DCEU entry, Millar decided to give us the "antidote to the antihero," setting aside all the political turmoil, deconstructionist tendencies, and uber realistic takes on superheroes in favor of something gentler and kinder. Thus, Huck was born. Not "Hulk," "Huck." There’s some smashing here…but a lot of surprising sweetness too.

Huck (Book 1): All-American

Writer: Mark Millar

Penciler: Rafael Albuquerque

Inker: Rafael Albuquerque

Colorist: Dave McCaig

Letterer: Nate Piekos

Issues Collected: Huck #1-6

Volume Publication Date: July 2016

Issue Publication Dates: November 2015-April 2016

Publisher: Image Comics

Though labeled "Book 1," Huck is a complete, six-issue series, penned by a guy with some familiarity with the Superman mythos. In the early 2000s, Millar scripted multiple issues of Superman Adventures, a series set within the Superman: The Animated Series continuity, as well as a handful of Action Comics issues and the Superman: Red Son limited series, where he turned Kal-El into a Communist. Though Red Son is an Elseworlds adventure reimagining the Man of Steel in a darker light, the series is a fascinating read precisely because it’s an alternative look at the cultural influence on Superman’s upbringing. Millar fashions the series as well as he does because he understands the character, and thanks to this understanding, he capably modifies and twists Superman’s core characteristics to tell a compelling story.

I say all that to underline what Man of Steel gets wrong about the character–you can’t just throw in a bit of violent murder and go, "See, Superman’s edgy and dark now." Millar keeps the heart of who Superman is intact, just dressing it up in a different guise at a different time and exploring the possibility of Superman’s innate protectiveness and heroism through a different definition guided by a different cultural lens. In short: if Millar makes Superman a bit nastier or more violent, it’s all in service to the story. Millar does not serve the darkness.

And Huck proves he can, when the occasion demands, rise from the shadows at his command and inject more lighthearted sensibilities into his narratives. Huck strives to be the opposite of Man of Steel, showcasing how Millar feels a true beacon of hope and help would behave. Separated from the political discourse of The Ultimates, the apocalyptic setting of Old Man Logan, or even the unequivocally imaginative violence of Wolverine: Enemy of the State (or the series' Image Comics contemporaries), Huck feels Millar at his most restrained…or, just maybe, his most liberated?

When I first heard about Huck’s basic premise–that Mark Millar, of all writers, was making a really nice Superman story, starring not an alien from another planet but an incredibly strong, somewhat naive gas station attendant–I tilted my head just a little. The guy who had Wolverine tear his way out of the Hulk after being eaten alive and blew up a school in Civil War was writing…something nice? It almost feels like a marketing gimmick by Image to drum up interest in the series. And were Huck to fall flat or wipe out narratively, I’d brush the imaginary dust off my hands and smugly report I was right. False alarm, people.

But Huck doesn’t fall, or wipe out. The series stands out as a "nice Superman story" precisely because it’s genuine, which is why I described Millar as "liberated" above. I’m not saying Millar tossed up a grim, angsty facade when penning his darker material–you can note the underlying themes of The Ultimates or Civil War (despite some heavy-handedness in both) and see a genuine concern in his writing. True tragedy drives the hearts of Old Man Logan and Enemy of the State. But I wonder, given the pervasive violence in these and other stories, Millar began to feel typecast in the role of "dark, cynical, violent comic book writer." Perhaps the experience of watching Man of Steel showed him, directly to his face, what happens when the postmodern sensibility so pervasive in comics (a phase Millar’s early 2000s narratives certainly contributed to) goes too far or becomes too ingrained and instilled in him the notion we need to take a few steps in the other direction.

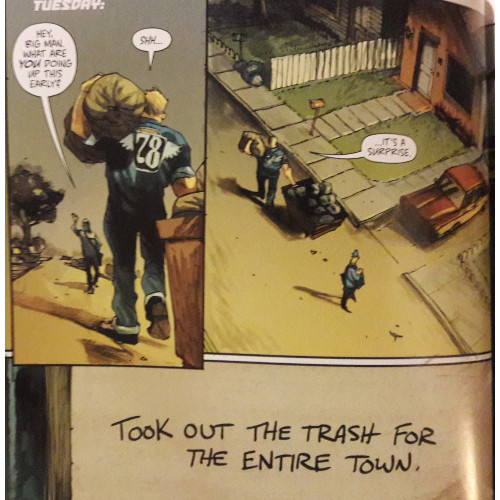

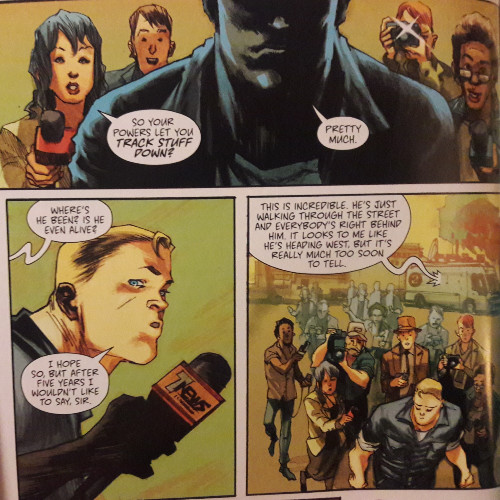

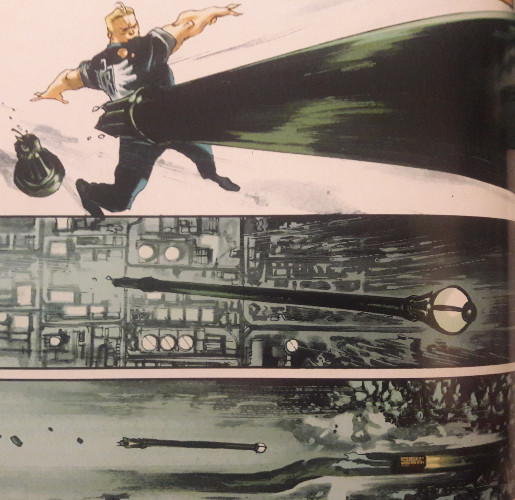

Huck centers around its eponymous hero, a man gifted with strength, seeming durability, and an uncanny sense of finding things. He’s a human bloodhound, capable of tracking down anything. Lost your keys? Huck can find them. Accidentally dropped a diamond ring in a river? Huck’s drawn right to it. Instead of using his special abilities to seek fame and fortune, Huck lives contentedly in the town where he was raised, plopped right down in the Middle-of-Nowhere USA. Every so often, he’ll take a little trip outta town–maybe he’s rescuing kidnapped girls from the Boko Haram out in North Africa or something like that. But he generally sticks to town, performing at least one good deed a day, enjoying his peace and quiet, yessir…until word of his abilities leaks to the press, and now, everyone wants a little piece of what Huck can offer.

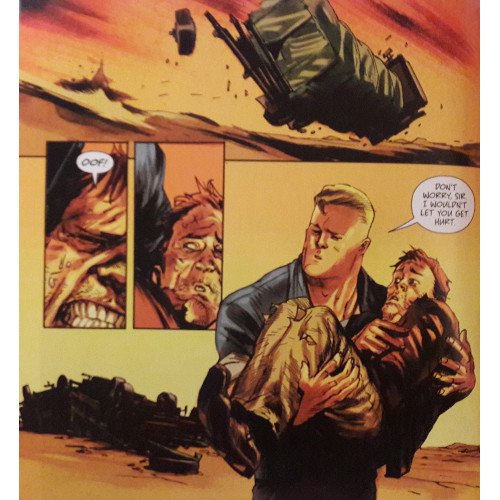

Huck’s an innocent, sweet guy, genuinely kind and caring, and it’s through him Millar really lays the groundwork for this "anti-antihero" concept. There’s not a cynical bone in this boy’s body, and though he might have to throw down when absolutely necessary, he’d rather just go about his business. He doesn’t swear, doesn’t drink, and can’t for the life of him pick up on a hint that a girl likes him. There’s a childlike quality to Huck’s demeanor as he interacts with people around him. Even the breaking news of his abilities doesn’t faze him; he just goes back to finding stuff for folks…and finding folks: a missing husband, a wayward daughter, a kidnapped brother.

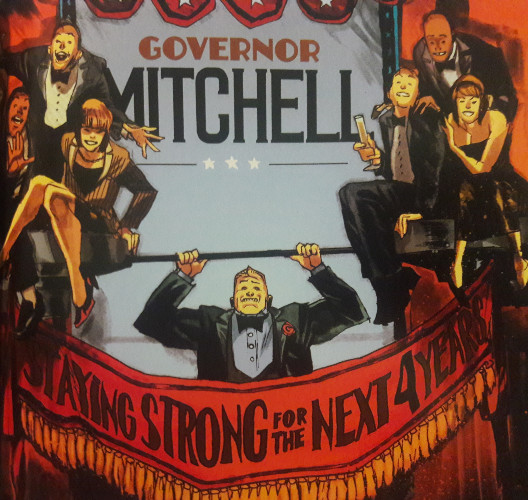

At the same time, Millar makes Huck wise. A few reviews I perused point out minor indications Huck may have a disability, which could explain his childlike demeanor. Yet, even if this is the case, Millar’s smart to give Huck a good sense of himself and who he is. When he’s invited to a shindig by the local governor and asked to perform a feat of strength, Huck knows he’s being treated as a sideshow and quickly abandons the party, but not before offering his newly empty hotel room to a few homeless men. He’s not manipulative, merely behaving kindly only to demand recompense from people later. He’s just nice. There’s no simpler way to say it than that.

Huck brings to mind Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale’s Superman For All Seasons, which primarily covers Clark Kent’s formative years in Smallville. Like Albuquerque’s Huck, Sale’s Clark is husky and broad-shouldered, somewhat whimsical as he ponders his life moving forward. Like Clark, Huck remains a citizen of a small community, helping out wherever. Huck has no aspirations of journeying to a big city or combating crime in a caped, cowled costume. He has no secret identity to slip back into. He’s a good guy, gifted with powers, who just wants to help.

Millar, fortunately, is aware that reading about a good guy, even one gifted with powers, walking around town and taking out people’s trash for six issues wouldn’t keep most readers entertained. He crafts a broader plot which pulls Huck and some other characters into a larger conspiracy. It’s a smart decision, and even if some elements feel randomly injected or happen a mite too quickly, Millar capably raises the stakes in ways which make sense and feel integral to developing the book’s central themes. Again, Huck doesn’t start snapping necks, but he’s placed in a position where he has to act a little more definitively, where the nice guy demeanor doesn’t necessarily fall away but becomes more determined and more protective given the situation. Let’s call it an extension of his character, applied to a much grander situation that requires a nobler effort…with perhaps a slight edge. Garbage isn’t the only kind of trash Huck takes out, we’ll say.

Periodically, Millar can inject a bit too much saccharine into Huck’s activities. Take the above example, where Huck offers his hotel room to two homeless men, with the promise of all the food they want, after a few panels where he feeds some stray cats. There is, perhaps, a bit too much pity thrown into the scene. Huck is wonderfully kind and an absolute counterpoint to the violent antiheroes (or even just more-violent-than-normal superheroes) we regularly witness in comics, but occasionally, Millar layers kindness upon kindness, and kindess2 just feels a tad overblown. I’m reminded of a scene from Red Son where Lex Luthor is introduced, playing seven simultaneous games of chess while teaching himself a new language. We get that Luthor’s obscenely intelligent, but Millar goes to such incredible lengths to show us just how intelligent Luthor is that the evidence rolls over into parody. How much more brilliant can we get than brilliant? How often do you need to show us Huck’s legitimate kindness to convince us he’s a pure soul?

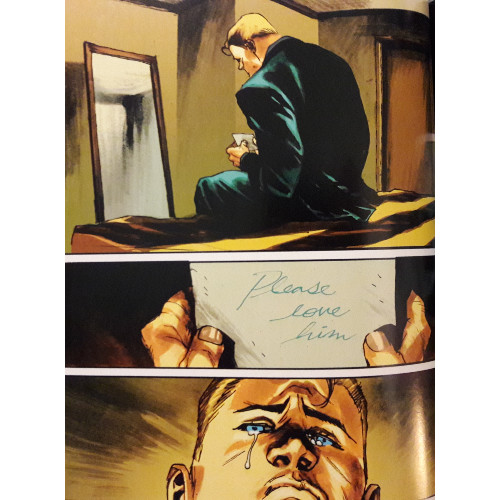

Taken all together, the series really demonstrates Huck’s core characteristic of compassion, and even if it’s ham-fisted at points (which certainly seems to be a consistent fault throughout Millar’s bibliography), the whole story is well-intentioned. Looking over the broader concept of kindness, we see the smaller brushstrokes. Huck, in his hotel room after leaving the party, holds a note which was attached to his basket as a baby: "Please love him." These three words drive his heart. His actions are a direct response to the love he’s been shown, and it’s this feeling which tempers Millar’s exaggerated depiction. The actions certainly speak for themselves, but in quiet moments, we understand the reasons underlying Huck’s actions…and those aren’t blatantly waved in front of our faces. We can juxtapose this scene with the governor’s shindig and bristle with frustration as a man innocent as Huck is used for political gain. We can draw parallels between Huck’s quiet, secretive manner and the snap decision of one person to sell his story to news outlets.

The back of the trade I own collecting the series labels Huck as "the feel-good comic of the year." It’s an accurate assessment. Unexpected but accurate. Yes, Millar can occasionally go overboard on the series’ sweet center, as if he’s removing himself from the dark climax of Man of Steel as much as possible and overcompensating as a result. But you honestly can’t complain too much of a hero who just wants to do the right thing by everyone. And if you can look past some of the sentimental specifics, you’ll find a series about a man who wants to give back the love he was shown by others. No manipulation. No financial gain. No political favor. It’s good knowing we have a superhero who’s just happy to help.