(Strand)om Stories: Black Panther: Doomwar Review

"Doomwar" offers genuine change for Wakanda and lives up to its promising premise, even if one of its main characters is handled less effectively than the plot

—by Nathan on February 23, 2023—

About a year ago, I ran the gamut of Reginald Hudlin’s run on Black Panther, taking three Complete Collections’ worth of material and scanning them through the analytical lens of a single blog post, similar to how I unpacked Christopher Priest’s run over at Geeks Under Grace. I found a series of stories that, though entertaining, didn’t pique my interest nearly as much as Priest’s time on the title. I discussed how Hudlin seemingly treated the past irreverently, with little inclination as to how some wonderful stories from years before could have shaped some of his characters and plots. Given my recent focus on T'Challa in a post on Spidey annuals from 1991, now seemed like a good time to explore the next chapters I've collected in the Panther's unfolding saga.

“Doomwar” seems like a culmination of sorts of Hudlin’s time on the title, serving as a confluence of a few different concepts–T’Challa’s changing role in Wakanda, Shuri’s adoption of the Black Panther identity, Storm and T’Challa’s marriage, and some mounting tensions in Wakanda. The “Doomwar” trade paperback I have collects both this story arc and a four-issue series centered on Shuri in a post-"Doomwar" world. I want to peer into that volume today and see how these tales fare against Hudlin’s prior work on the Wakandan Avenger.

Black Panther: Doomwar

Writers: Reginald Hudlin, Jonathan Mayberry

Pencilers: Will Conrad, Ken Lashley, Scott Eaton, Shawn Moll, Gianluca Gugliotta, Pepe Larraz

Inkers: Will Conrad, Paul Neary, Andy Lanning, Robert Campanella, Jaime Mendoza, Dave Meikis, Walden Wong, Gianluca Gugliotta

Colorists: Peter Pantazis, Jean-Francois Beaulieu, Edgar Delgado, Jose Villarrubia

Letterers: VC's Cory Petit, Clayton Cowles, Joe Caramanga, Dave Lanphear, Comicraft's Albert Deschesne

Issues: Black Panther (2009) #7-12, Doomwar #1-6, Klaws of the Panther #1-4, and material from Age of Heroes #4

Volume Publication Date: February 2017

Issue Publication Dates: October 2009-October 2010, December 2010-February 2011

For several posts, I have discussed T’Challa’s role as the Black Panther and how various writers (Don McGregor, Jack Kirby, Christopher Priest) shaped his character and stories over the last several decades. For the entirety of this volume, however, a new individual has donned the ceremonial cape and cowl of Wakanda’s ruler and defender: Shuri, T’Challa’s sister.

I noted this briefly in my post covering Hudlin’s run, but Shuri’s introduction to the Marvel Universe is a tad awkward. She shows up in the second issue of Hudlin’s run, in the middle of a revamped origin story Hudlin created for T’Challa. As a reader, you’re supposed to immediately believe that Shuri has been present this entire time, some young girl hiding in the shadows of her father and brother’s preeminence. Retroactively, I suppose, you’re meant to just plop her down into the background of McGregor’s “Panther’s Rage” or Priest’s run and just assume she’s been there...doing...something?

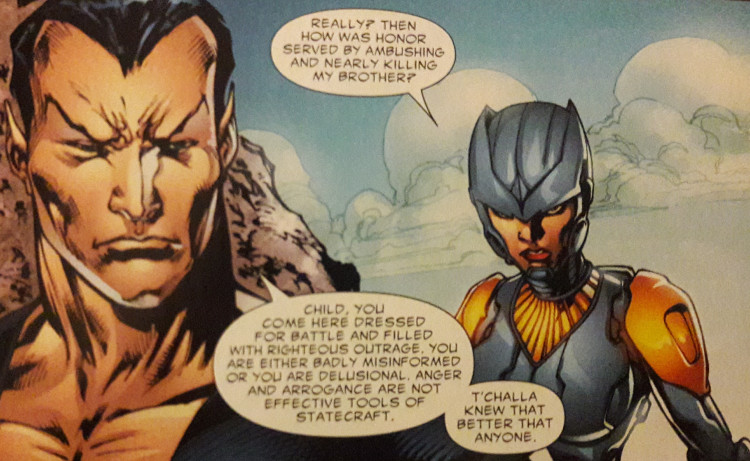

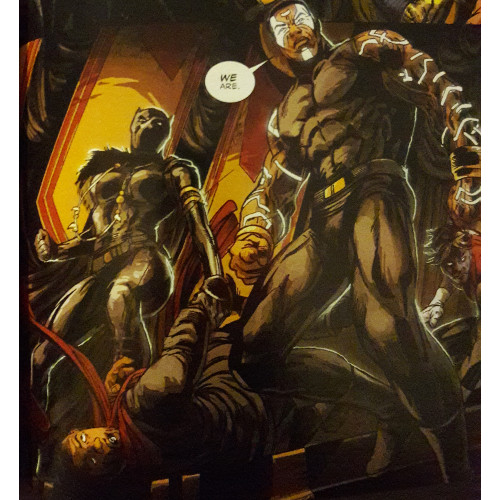

What’s frustrating is that neither Hudlin nor Mayberry take the time to unpack Shuri’s history, and for a story where she plays such a vital role, I find her difficult to follow and empathize with. We’re consistently given new bits of information about her as the main “Doomwar” story and its “Klaws of the Panther” follow-up progress–she’s incredibly smart, she’s a bit of a party animal, she’s got these violent, almost animalistic tendencies. In a way, it makes sense. The writers, not having time to shape her previously, need to get readers on board with who this character is and what she’s able to offer the mythos. To me, she’s intended to be a foil to T’Challa–she’s intelligent but she doesn’t necessarily possess his cunning or calm. She’s this girl who’s always wanted to wrest the Black Panther mantle from her brother but, now that she has it, is uncertain about how best to fit that role–similar to how the MCU’s Shuri needed to navigate the complexity of the mantle in Wakanda Forever. Much of this collection feels almost like an “origin” or “coming of age” story for Shuri, and as well as she undergoes this “baptism of fire,” it feels somewhat undeserved.

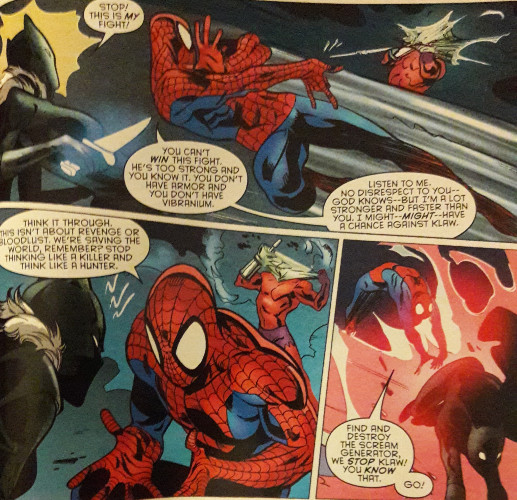

For example, check out the “Klaws of the Panther” limited series at the end of the volume. Shuri, inadvertently on the trail of her brother’s old enemy Klaw, teams up with other Marvel heroes such as Spider-Man, Wolverine, Black Widow, and Ka-Zar and his wife Shanna the She-Devil. The whole series feels like this extended conversation between Shuri and these other heroes about her penchant for hot-headedness and violence; after a while, the discussion becomes stale. I get the idea–Shuri really needs to grow past her childish proclivities and assume the more adult responsibilities encompassed by her new mantle–but to have the idea repeated ad nauseam, with only the wording of arguments altered slightly, becomes stale.

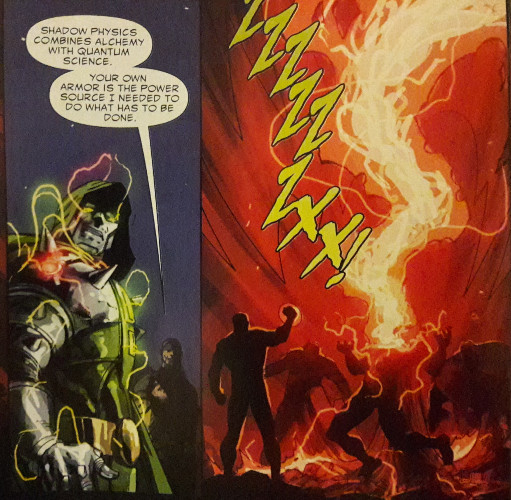

The primary story deals with conflict between Doctor Doom and the Black Panther and chimes in on an idea I recall first seeded in Priest’s run: the competitive nature of monarchs. I don’t know how often Doctor Doom and Panther sniped at one another before this arc was published (Priest’s conflict also involved Magneto and Namor, but Hudlin certainly planted seeds before this), but the concept of the two monarchs taking pot shots or seeing each other as rivals feel so natural I wonder why writers haven’t more frequently pitted the two men against one another. The match is perfect, almost as strong, theoretically, as the actual rivalry between Doom and Reed Richards, the incredibly smart and elastic Mr. Fantastic. On the one hand, you have the insanely intelligent and snide yet downright arrogant Doctor Doom, lord of a tiny European nation, pitted against the similarly intelligent yet much more humble T’Challa, king of a powerful African country. You’ve got issues of race, nationalism, intelligence, attitude, military might, physical prowess...there’s a lot you could unpack here.

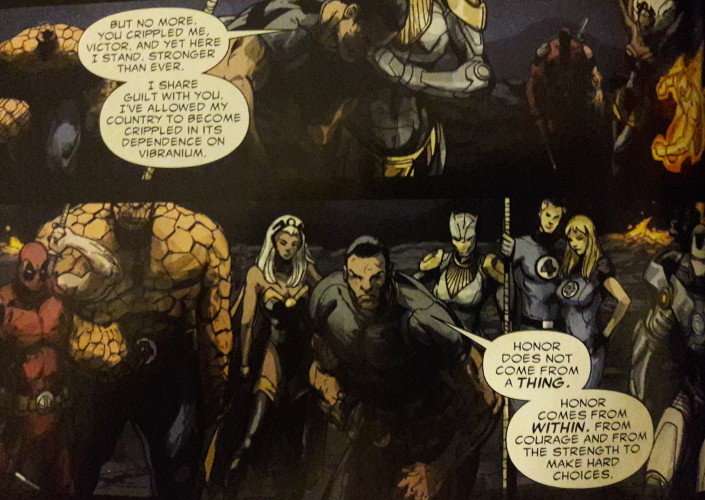

Am I somewhat salty, then, that Doom’s primary foe is Shuri? Not really. Mayberry seeds T’Challa into this whole arc nicely, balancing out Shuri’s new role as the Panther with T’Challa’s own craftiness and the steps he believes necessary to safeguard his kingdom. Deprived of the Black Panther’s strength, T’Challa is forced to consider other possibilities, relying on his wit and allies in a way he’s never had to before. Priest’s T’Challa never found himself 100% reliant on friends, usually discovering his own ways out of tricks and traps. This T’Challa, however, is forced to set aside some of that independence as he struggles to save his kingdom.

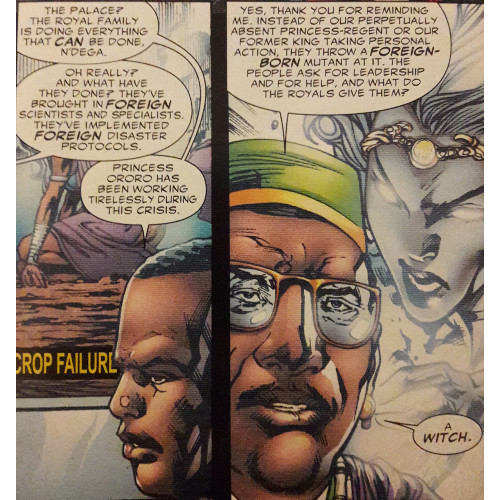

Wakanda itself, in the grip of terror as Doom plots alongside an anti-Panther extremist group, comes to life in a way few writers have embraced. Don McGregor was the writer to truly establish Wakanda as a nation, with Jack Kirby and Christopher Priest picking up on those ideas during their runs on the Panther. Wakanda has flourished in readers’ imaginations over the last several decades, becoming a fully realized world and not just “that one hidden country with a super powerful metal.” Mayberry, artfully, focuses on the people of Wakanda and, perhaps for the first time in my reading experience, truly captures the citizenry of the country.

Panther has always discussed protecting his people, yet unfortunately, I recall very few “man on the street” scenes from prior writers or at least scenes which honed in on the thoughts and feelings of Wakandans. Mayberry provides this commentary, rather literally, by crafting two news channel deliberators, who bandy about politics as Wakanda becomes more and more internally vulnerable. My mind flashed back to Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, where the writer expertly used “talking heads” to convey the thoughts and opinions of random Gothamites on the actions of the newly returned Batman. Similarly, Mayberry uses his show hosts to get a sense of how the Wakandan people are genuinely reacting to the insanity around them.

For the first time, you get a sense of how truly vulnerable Wakanda is, how truly close they are to being conquered. Throughout almost every Black Panther story, the impenetrability, the incorruptibility of his nation home is stressed time and again. Wakanda is hidden, unconquerable. Yet here, Mayberry flips the script, presenting a Wakanda on the brink. What would happen if Wakanda really was taken over, removed from the Panther’s grasp?

Also adequately explored is a neat bit of plot development near the story’s end, an idea seeded in its culminating chapter. I wish to forego discussing this concept at length, as to not spoil "Doomwar," but at the time of the story's publication, the twist bore the potential to change the face of Wakanda and the Black Panther forever. The twist has since been undone (after Jonathan Hickman’s Secret Wars crossover), but the notion is fascinating. T’Challa makes a seemingly catastrophic decision to save his people, and though I’m not much in a position to argue for or against the merits of such a choice, it radically redefines his place in the world as well as Wakanda itself. It’s a bold decision on his part and on the part of Mayberry.

Though temporary, the change is fantastic for one massive reason: the general sameness of comic book stories. There’s an argument often made about the “illusion of change,” that even climactic, monumental, life-altering events in comic books are often reneged upon at some point. Spider-Man went through two whole years of change during the “Clone Saga”–where Marvel revealed he was a clone, replaced him with the “real” Peter Parker (Ben Reilly), killed his aunt, relocated him to Oregon, stole his powers, and teased the promise of his and MJ’s child...only to have most of that yanked back once the dust settled. Ben Reily was actually the clone the whole time. Aunt May was alive. Peter moved back to New York. His powers returned. MJ lost the child. Everything that Marvel touted as one earth-shattering change after another faded quickly.

Fortunately, the alteration I discussed above remained for at least a short while. It dramatically altered some Panther stories down the road (a series of which I hope to examine at some point in the future). I’m reminded of Thor: Ragnarok, which ends with the destruction of Asgard. The move incorporates real change, real loss, and Mayberry injects that nicely into this comic book arc as well. Though eventually upended by Secret Wars, this twist momentarily promised that T’Challa’s life would move in a radically different direction. In this case, I don’t think it necessarily mattered that the twist was eventually undone. “The Clone Saga” promised to dramatically alter Peter Parker’s life...and it didn’t. “Doomwar” promised to change the course of T’Challa’s existence...and, for a time, it did that.

I leave this story with a respect for the changes introduced and the way Hudlin and Mayberry went about disrupting Wakanda–using Doctor Doom as an impetus for this change, and as a prime antagonist for the story overall, is a fantastic decision and is incorporated wonderfully into the plot. I still struggle with accepting Shuri as the Black Panther–I understand the decision, and though I could not tell whether Hudlin introduced her in his run to eventually have her claim the title, I can see it as a justifiable possibility. I’m just not endeared to her character, but part of this may be due to poor character building on Hudlin’s part before he had her take over the mantle. I am still, quite fortunately, a T’Challa fan; I can’t say this story ranks above what writers like McGregor and Priest have constructed, but Mayberry has done the bulk of the work in crafting an engaging political thriller around T’Challa and his family, ending with a startling revelation that, for a time, offered real change to both Wakanda and the wider Marvel Universe.