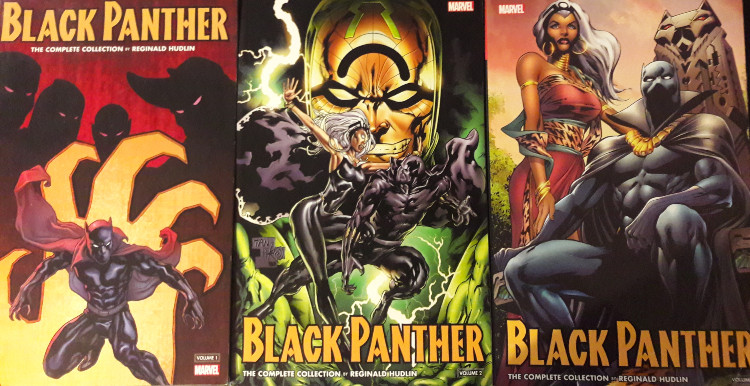

(Strand)om Stories: Black Panther by Reginald Hudlin: The Complete Collection (Vols. 1-3) Review

Reginald Hudlin's run is frustrating, dismissive of past narratives while forming engaging plots in the present

—by Nathan on January 22, 2022—

This review will be done in a slightly different fashion than some of my others. Back when I bought several volumes collecting multiple Black Panther arcs from the early 2000s, I intended on reviewing them volume-by-volume, as I have done with Panther's Epic Collections and other Marvel narratives such as Frank Miller’s run on Daredevil and Chris Claremont’s era of Uncanny X-Men. In the middle of this, however, I published a review of Christopher Priest’s excellent Black Panther run with Geeks Under Grace, thus rendering the posts I intended on using to cover his series redundant. While I could have tackled each portion a piece at a time, I realized that I’d end up repeating myself often, something I wanted to avoid.

I actually really enjoyed covering Priest’s run in one fell swoop, encouraging me to do the same for Hudlin’s run on the title here. I have three volumes which collect Hudlin’s run, but I wish to simply delve into the entire thing instead of looking at it piecemeal. I’m interested in seeing how this type of review will go...will I end up enjoying covering this much material in a one-and-done fashion? Or will I feel like I’m glossing over too much? Thus, much like a Wakandan scientist manipulating his nation’s fabled vibranium, I wish to toy with the fabric and structure of my typical ploys...and hope to find some malleability beneath the surface.

Black Panther by Reginald Hudlin: The Complete Collection (Vols. 1-3)

Writers: Reginald Hudlin, Peter Milligan, Jason Aaron

Artists: John Romita Jr., Trevor Hairsine, David Yardin, Scot Eaton, Kaare Andrews, Salvadore Larroca, Manuel Garcia, Kai Turnbull, Marcus To, Francis Portela, Andrea Di Vito, CAFU, Ken Lashley, Larry Stroman, Jefte Palo, and Denys Cowan

Issues: Black Panther (2005) #1-41, Black Panther (2005) Annual #1, Black Panther (2009) #1-6, Black Panther/Captain America: Flags of Our Fathers #1-4, Black Panther Saga, and X-Men (1991) #175-176

Volume Publication Dates: November 2017, January-February 2018

Issue Publication Dates: April 2005-November 2008, April 2009-September 2009, June 2010-September 2010

A brief distinction: though I have clearly labeled this as “Reginald Hudlin’s run,” I have included, as you will see, a few other writers. For the sake of the review, I have decided to review everything I have collected in the volumes which cover Hudlin’s contributions to Panther’s mythology. Thus, a few other stories and creators have slipped in.

Hudlin’s run, to not put too fine a panther talon on it, is frustrating to contend with on a personal level. Much of my dissatisfaction relates to Hudlin's work being a direct follow up to Christopher Priest’s run on the title launched during the Marvel Knights era. Priest’s series is a beloved favorite, a thoroughly engaging examination of T’Challa and his world, constructed as a political thriller/satire and wrapped in a series of beautiful nods to the past, particularly the work of Jack Kirby and the exceptional narrative prowess of Don McGregor.

Hudlin doesn’t seem to care much.

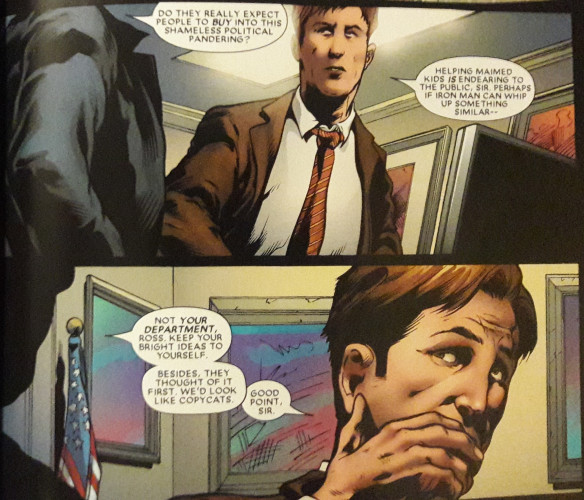

Holdovers from Priest’s run are evident: Hudlin incorporates the Dora Milaje (Panther’s bodyguards/wives-in-training), which Priest instituted, as well as Everett K. Ross, United States government attache to T’Challa and one of the single most important characters to Priest’s run (outside of T’Challa himself, perhaps the most important). But while Hudlin includes these characters, he scraps everything else Priest did with them. The Dora Milaje--complexly crafted and given narrative subplots and personalities by Priest--are made into faceless bodyguards with zero personality and a couple of names tossed in every so often. Ross--who served not only a comic relief position but was made to be Priest’s “everyman” audience surrogate--is a cold, distant, poor approximation of the character he was originally created to be.

I get that following up a high act such as Priest’s would be intimidating, and I know comic authors are prone to sideline or retcon the work of previous authors, particularly if that work has been dismally received. I had a good chuckle when Nick Spencer, in his opening arc on Amazing Spider-Man, revoked the doctorate writer Dan Slott had given Peter Parker via Otto Octavius’s mental switcheroo in an attempt to bring Peter “back to basics.” But Hudlin doesn’t seem to be making such a statement, nor is Priest’s run held in such low regard that such casual dismissal of his contributions feels appropriate. Here and there lay scattered references to Priest’s work, but these are incorporated as mere references and not given the historical weight that Priest infuses in his own nods to previous creators.

I did not look at Hudlin as Priest’s “successor” in any way other than chronological--he simply took the book over and relaunched the title after Priest’s departure. Nor did I wish Hudlin to continue the exact same style as Priest’s. But for Hudlin to so quickly remove himself from Priest’s stories is a point of contention for me.

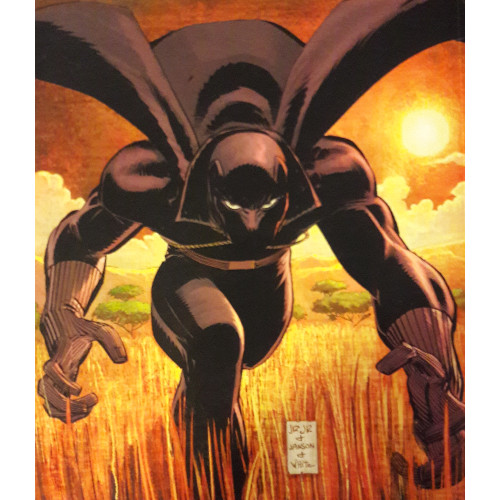

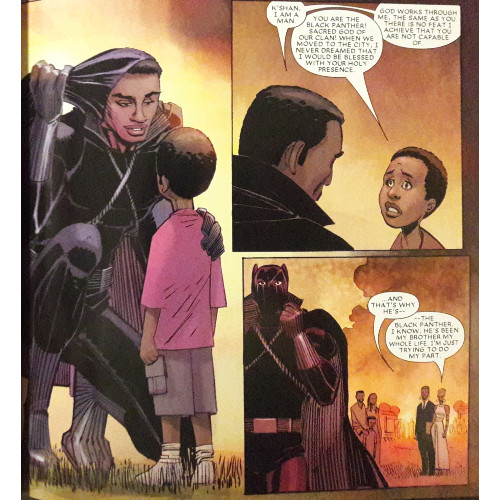

Hudlin’s take on the Panther is not bizarre or unconventional--clearly, the one specific piece Hudlin pulls in from Priest’s run is the “Batman” quality Priest gave T’Challa. This T’Challa is still two steps ahead of everyone and admirably strives to protect his kingdom and people. In fact, I’d argue Hudlin humanizes T’Challa a little more than Priest. Priest’s Panther can, occasionally, feel distant and unknowable, given this aura of mystique that very few people are able to penetrate. Hudlin’s T’Challa feels more accessible to the audience and, in some ways, is given a chance to grow. He marries mutant superheroine and X-Man Storm, their relationship forming a long-running theme throughout Hudlin’s run. His T’Challa isn’t given to super incredible plotting that he seemingly pulls out of a hat (one of my few complaints regarding Priest’s run is how often T’Challa had a solution for just about every problem he faced); his T’Challa fails and falls, and though he’s a genius, there are moments where he feels genuinely human. It's also worth noting that T'Challa's "humanity," as defined by both Priest and Hudlin, is not merely based on his ability to absorb physical punishment or push past his limits, a tactic McGregor used several times.

Unlike Priest, Hudlin feels like he’s in a position where he needs to graft in more of the ongoing developments in the Marvel Universe overall. Thus, much of Hudlin’s run deals with events such as House of M, Civil War, and Secret Invasion. The House of M tie-in, coming on the heels of Hudlin’s rewritten origin of the Black Panther, feels the most egregiously out of place and stilted. It comes out of nowhere, transporting T’Challa into a world controlled by Magneto, and ending as abruptly as it began. The story would have been better served, I believe, by a miniseries dedicated to unpacking T’Challa’s role in the new world instead of skipping through a couple issues of the main title.

The Civil War tie-ins feel more pertinent and take up a decent chunk of Hudlin’s run. Hudlin navigates this story better, analyzing both T’Challa and Storm’s roles in the world once the Superhuman Registration Act is passed. Hudlin keenly ties the issue of superhuman surveillance to both Storm’s history as a mutant and Panther’s perspective as an African man living in a Western world and as the king of a nation with coveted resources. Hudlin has the appropriate space and time to deal with their responses to the developing issues, stressing their relationships with both the pro-Registration faction led by Iron Man and the resistance movement led by Captain America. At moments, Hudlin feels like he’s repeating himself a little, but despite some needlessly reiterated concepts, he genuinely explores some of Civil War’s philosophical notions, perhaps even better than Mark Millar did in the main series.

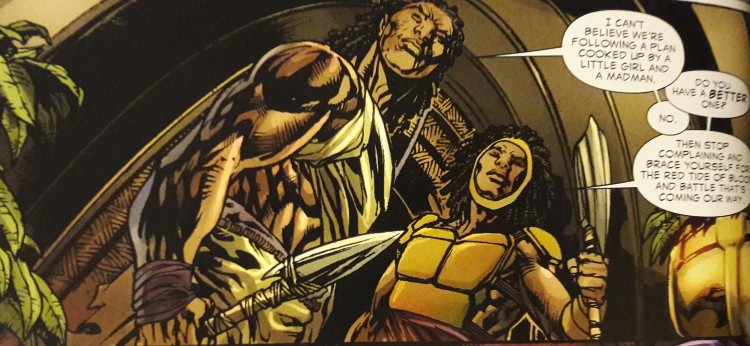

Funnily enough, it’s the Secret Invasion tie-in issues, penned by Jason Aaron, which represent the high-water mark on the title. Aaron’s T’Challa is at his finest, which is to say, his most Priest-like. Aaron crafts a genuinely engaging story which sees the Skrulls attempt to take over Wakanda during their Secret Invasion of Earth. His Panther is at the ready, with plans within plans to take on the oncoming Skrull army. From the get go, you as the reader know how this is going to go, you know the Skrulls are gonna end up decimated or wholly thwarted in their plans to conquer Wakanda. Yet it’s how Aaron crafts the journey to that moment of victory, how he seeds twists and uncertainties, that makes the story so gripping. The ending is fully justified. Interwoven is narrative commentary directed by a Skrull captain; watching how his personal story unfolds--particularly his perspective on his enemy--offers a sense of irony. Again, from the start, you can’t help but smile and think to yourself, You’re a goner, guy. It’s just a matter of “how” and “when.” An exceptionally executed arc.

When Hudlin deviates from the ongoing events in the larger Marvel Universe, he shines. He introduces Shuri, T’Challa’s sister, perhaps his greatest contribution to the Panther mythos. Shuri’s introduction is a little awkward, Hudlin just plopping her into the story--but how else do you introduce a character who’s supposed to have history but never technically existed until her first appearance in 2005? Shuri becomes an interesting figure throughout the series, breaking out on her own during a period where she replaces T’Challa as the Panther. Hudlin (and a few future writers) craft her as a headstrong teenager with a more wild side than T’Challa possesses. She contrasts T’Challa nicely, Hudlin putting her in a spot where she’s forced to grow when her time to assume the mantle comes along.

Other characters are bandied about in interesting ways as well. A brief arc sees T’Challa and Storm team with Ben Grimm and Johnny Storm, latching onto Panther’s strong roots with the Fantastic Four. W’kabi and Zuri, characters introduced by Don McGregor and Priest respectively, are utilized sparingly, yet both men make a desperate stand against a powerful foe late in the series; given Hudlin’s standard unwillingness to peer into the past, this moment stands in my mind as an actually decent representation of two characters from prior narratives. Without McGregor and Priest’s narratives, I think, the scene wouldn’t work as well...it’s perhaps the one moment in his whole run where Hudlin adequately acknowledges the past and recognizes where he is presently because of the writers before him.

Perhaps that’s a good way of noting my frustration with how Hudlin shapes his series. He does not appear to openly acknowledge how Panther has worked his way through the past and gotten to the present. When Erik Killmonger threatens Wakanda, scant reference is made to past schemes. I think I expected him to be treated like the Green Goblin, a character who we’re never allowed to forget killed Gwen Stacy or learned Spider-Man’s identity or kidnapped however many friends and allies of Peter Parker’s. It’s like Hudlin expects Killmonger, and perhaps some other characters, to inherently carry a weight of history and menace someone like the Goblin, Lex Luthor, the Joker, Magneto, or the Red Skull can. And maybe to some readers more familiar with Panther’s history, he does. But part of me wishes Hudlin was a little proactive in acknowledging the past--someone only alludes to that one time Killmonger tossed T’Challa off a waterfall. This is a guy who nearly conquered Wakanda on more than one occasion. He deserves some mention.

I don’t know why Hudlin is so lip-locked about referencing the past or at least offering it the respect and acknowledgment it deserves. T’Challa’s history may not be as extensive as some other characters, but to me, that’s even more of a reason to bring it up, build off it, use it. Perhaps a good way of wording my general complaint is that Hudlin approaches the series as someone who’s a fan of the “Black Panther” idea without understanding the depth of the character. He plays a little loose with the history, barely referencing even big ideas and stories, while not taking the proper time to incorporate the continuity in engaging ways.

There are some nicely creative moments to this series. Hudlin, for the little he does stay in the past, does form a couple of engaging plot threads on his own. He builds the Panther/Storm relationship, introduces a fun new character with Shuri, weaves in some larger themes as he works his way through Civil War. As I said earlier, when he’s able to work on his own away from the past, he does well and invents intriguing narratives. But his ability to weave in prior stories, characters, perhaps even some cultural elements tends to feel a little lacking.

Hudlin’s run is one I intend on checking out again, perhaps more immediately after finishing Priest’s whenever I read that again (because I certainly will) and perhaps in a more sequential order than I did tackling Hudlin’s work this first time around. A second time may help me coalesce just what exactly are the strengths of the run rather than the weaknesses. I don’t have “panther sight,” sadly. I see things a little more skewed towards my own preferences. And, in this case, I often found myself wanting to dangle the book over a waterfall rather than sitting it next to the kingly work of the Priest.