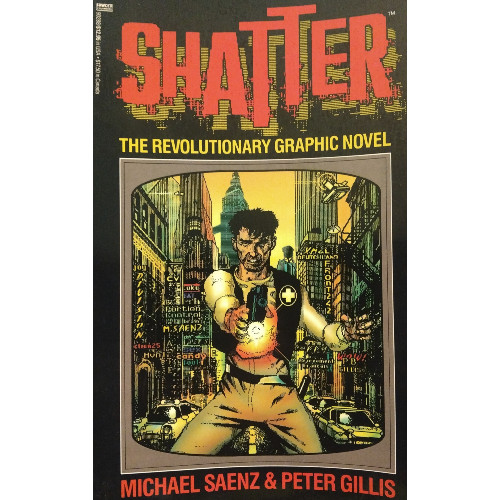

Random Reviews: Shatter

A clever artistic method is born in an innovative graphic novel, subsequent issues belaying strong storytelling in favor of a unique atmosphere

—by Nathan on October 14, 2025—

A short while back, I reviewed a volume of Iron Man comics which included the graphic novel Iron Man: Crash. Crash has the distinction of being the first graphic novel rendered completely on a computer–I say "completely," because creators Mike Saenz (who did the writing and illustrating) and William Bates (who performed the programming) produced penciling, inking, coloring, and lettering for Crash through a computer. This is why the cover touts Crash as the "first computer generated graphic novel."

It's a claim that feels ever so slightly hair-splitty to me.

Two years before Crash was published, Saenz introduced what I feel really should be considered the first graphic novel generated by a computer: Shatter. I guess Saenz really likes verbs evoking the concept of breaking, because that's what he endeavored here: breaking the bonds of artistic limitation through the application of technology. Crash may be considered the first because some of the procedures in developing Shatter, such as coloring, were done in the traditional style. Maybe that discounts it, or maybe I'm just being a little cynical.

Since I reviewed Crash and was aware of Saenz's other pet project, I wanted to give this graphic novel a try. Two surprises awaited me: first, Saenz did not develop just a Shatter graphic novel for publisher First Comics but continued the concept in back-up strips in Mike Grell's Jon Sable, Freelance and a short Shatter ongoing series. Second, Peter B. Gillis wrote the first issue. I have a bit of a rough opinion of Gillis' work–though I am not a fan of a certain Doctor Strange story arc he wrote, I do appreciate his Eternals limited series and am hoping to review his unsung Strikeforce Morituri fairly soon (seriously, a genuine hidden gem from Marvel's 80s library). Saenz provides the other narratives in the volume, but Gillis kicks off the adventure with aplomb, as we shall see.

Welcome to the future. It's a digital world rendered in a digital style. As Gillis writes in an introduction, this is "a story about a world changed by technology," and you get the idea he's slyly pointing to both where Shatter (the man, not the series) lives…and where we do.

Shatter

Writers: Peter B. Gillis, Mike Saenz (with assists from Mark Pierce and Kenn Frandsen), and Steven Grant

Pencilers: Mike Saenz (with assists from Mark Pierce and Bert Monroy), Steve Erwin, and Bob Dienethal

Inker: Mike Saenz (with assists from Mark Pierce)

Colorists: Mike Saenz, Janice Cohen, Alex Wald, Les Dorscheid

Letterers: Mike Saenz and Rick Oliver

Issues: Shatter Special #1, Jon Sable, Freelancer #25-30, Shatter #1-4

Volume Publication Date: April 1988

Issue Publication Dates: June 1985-December 1985, February 1986, June 1986, August 1986

Publisher: First Comics (issues), Ballantine Books (volume)

It feels important, in reviewing a comic where most of the production was rendered on a computer, to begin with discussing the artistic style. Or "style"? It feels like a weird word to apply here.

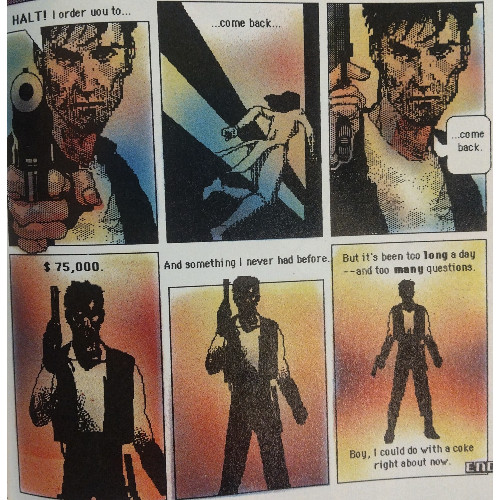

I made a few critiques regarding the art of Crash, noting how it did a serviceable job applying computer technology to the graphic medium. It created a story you could easily read and follow, utilizing the creative talents of the individuals involved in a unique method. I felt, however, that because the digital process was in its infancy, you could easily discern the discrepancies between digital art and pen-to-paper art. There was a coldness to Crash, a lack of fluidity between panels, no discernible style.

Much of that is, to my (I guess, third) surprise, not as great an issue with Shatter.

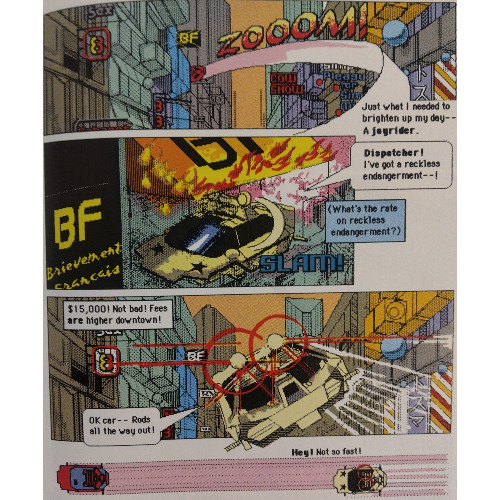

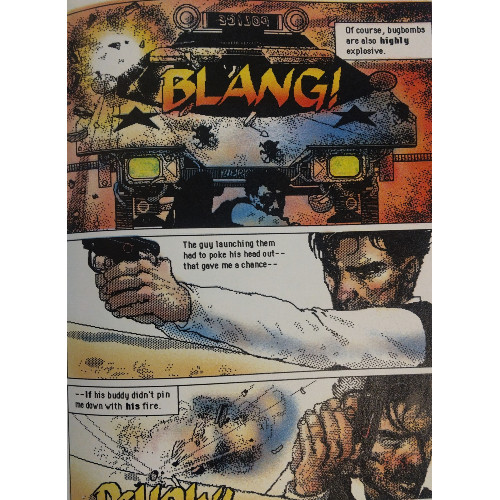

I assume, because some of the artwork was completed by hand, Saenz had a bit more physical control over the finished product here. You can still tell the first graphic novel and subsequent issues were created using a computer–there is still a certain blockiness to the art, a whole lotta dots comprising each image, and the occasional awkward rendition of a person or plot point–but because, I suspect, the human element was more prevalent, it looks better than a graphic novel created two years later. Details feel more apparent, as do efforts at shading. I enjoyed the art more, at least. There is still not much of a discernible style, not at least in the way that traditional artists give their characters or backgrounds, but there is the emergence of substance–gritty, sometimes grainy, but we have developed characters moving within a developed world.

"Shatter" is the nickname of Sadir al-din Morales (who, it's implied, is not actually Arabic, the name a nepotistic joke made by his parents), a "temp" who lives in a Chicago of the future. As a temp, Shatter is employed to pull off all kinds of dangerous bounty hunting jobs, tracking down killers for that sweet, sweet cash so he can get his fix: Coke. Yeah, "Coke" with a capital "C," because our man likes his soda, which seems somewhat of a rarity in the future Chicago. It's a unique motivation, but it's part of the character's charm.

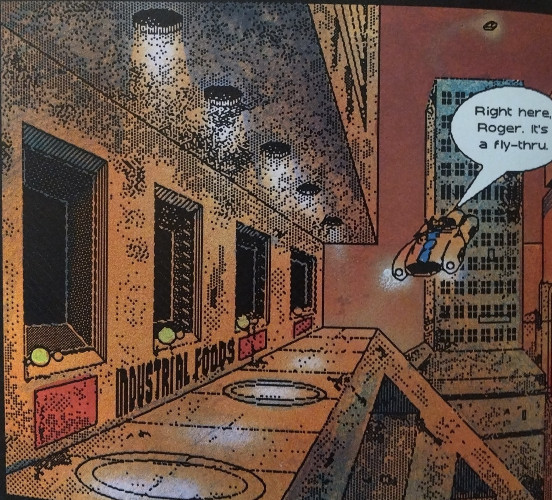

Gillis, in crafting the first issue, does a lotta legwork in establishing Shatter and this world he lives in. Gillis is a master at worldbuilding, so he develops, with Saenz, a Chicago where flying cars are prevalent and dock right at your home, bombs are shaped like mechanical beetles, and the most recent drug can inject another person's skills right into your bloodstream. Wanna play piano? Easy enough. Just hijack the RNA of someone who can play piano and inject yourself. Sure, there are drawbacks: you only get the skills for one year, the process only gives you the ability but not the knowledge (you'd still have to learn to play piano yourself, in other words), and the other person's brain needs to be removed to get the RNA, but…a pretty good deal otherwise, right?

I love stories where high-concept, futuristic technology and ideas can be applied in a frighteningly relatable manner. Imagine a world where brain matter can be harvested to sell skills to people and where cars can fly. It's a world out of our dreams...yet it's still wrapped in gaudy reality. In this Chicago, you'd still find yourself bombarded by advertisements on all sides–this Chicago still has fast food joints and convenience stores; they're just a little higher up in the sky so their neon lights and "fly-thru"s can attract drivers cruising the skies. It's a world, much like Gillis notes in the intro, that truly has been changed by technology…yet demands to maintain some of the same corruption and consumerist ideologies which run rampant in our own world. Gillis and Saenz are never preachy about any of this, letting the reader notice the similarities between our own society and the one where Shatter operates.

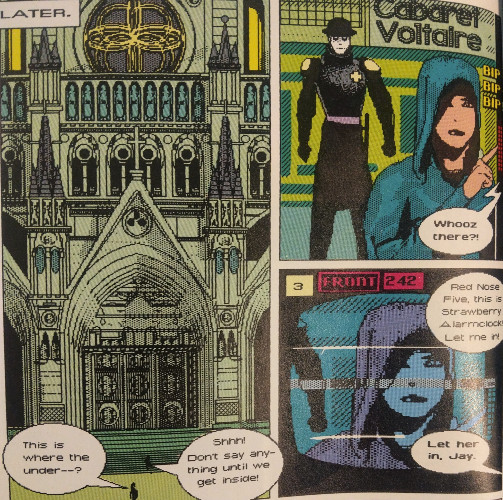

Much of the story–particularly after the original graphic novel, where writing is taken over by Saenz and then Punisher writer Steven Grant–becomes your tried-and-true sci-fi dystopian adventure: Shatter, involved to some extent in the business world, becomes disillusioned and joins a group of resistance fighters seeking to prevent a powerful organization from monopolizing on this black market RNA process. This leads to a whole buncha skirmishes where good guys and bad guys exchange gunfire and bug bombs. By the time we reach the Shatter series' fourth issue, the plot is largely wrapped up in a mostly satisfactory manner. If you know your future sci-fi stories, you'll be right at home here, though don't expect anything subversive or surprising.

I do feel the narrative gets away from Saenz and Grant at moments–we're introduced to several eccentric characters who only leave a small impression on the reader; a twist two-thirds of the way through lands well enough but feels a little forced; and a late plot development steers the narrative in a slightly different, somewhat distracting, direction. We get a surprising amount of pieces to keep track of across these issues, especially the smaller back-up strips in the John Sable issues, and I found that as the plot grew and the cast expanded, I cared less for the newer elements introduced.

The graphic novel remains the most interesting story told in this volume, so for readers interested in Shatter, you're encouraged to pick up the standalone first chapter. It feels, though not completely finished, satisfactory, placing Shatter in a place where he begins to question his role in society…and other, more powerful people's roles in society as well. The stories which follow are entertaining, but they lack Gillis' wit. The visuals work well to tell the tale and immerse you in the future, and if you just like watching flying cars zoom around the Chicago skies, you'll appreciate what comes after the first installment. The concepts are solid, but the story told is not nearly as innovative as the artistic process used to bring this world to digital life.