(Strand)om Stories: The Eternals: The Dreaming Celestial Saga Review

This volume contains several stories which work to wonderfully plant the Eternals firmly into the Marvel Universe

—by Nathan on August 1, 2021—

So far, we’ve covered two different volumes containing two different arcs centered on Marvel’s immortal icons, the Eternals. These demigod doers of good, created by Jack Kirby in the 70s, were originally invented to showcase a saga on our planet, Kirby’s mystical account of mankind’s creation. There, the Eternals represented a strain of superhumans invented by the galactic Celestials, and by their nature, opposed the more deformed, darker Deviants the Celestials also created.

Roy Thomas, a few years later, pulled the Eternals, Deviants, and Celestials into the Marvel Universe proper, tying up loose ends left by the sudden cancellation of Kirby’s original series. Via a particular golden-haired son of Odin, Thomas forged an epic the kind of which spanned not only the Norse and Eternal pantheons but also ushered in other deities. The Marvel Universe was, rather abruptly, bursting with gods and godlike heroes.

Now that the Eternals no longer stood on their own, writers had the opportunity to integrate them further into the Marvel Universe. That’s the main reason a fan of the characters would want to pick up this particular volume. We’ve seen the Eternals stand alone, and we’ve seen them enter the Marvel world of comic book glory aside Thor. But how well do these ancient champions fare enmeshed in a universe where they are no longer Earth’s only champions?

The Eternals: The Dreaming Celestial Saga

Writers: Peter B. Gilis, Walt Simonson, Roger Stern, Marc Gruenwald, Ralph Macchio

Pencilers: Sal Buscema, Al Milgrom, Keith Pollard, Paul Ryan, Ron Wilson, Rich Buckler, Luke McDonnell

Issues Collected: The Eternals (vol. 2) #1-12, Iron Man Annual #6, Avengers #246-248, and material from What If-? (vol. 1) #23-30

Volume Publication Date: January 2021

Issues Publication Dates: October 1980-November 1981, November 1983, September 1984-October 1984, October 1985-September 1986

When Roy Thomas reached into the Kirby-verse and grabbed the King's Eternal action figures, the writer didn’t seem to have a particularly defined idea about what he was doing. “Get the Eternals into the Marvel Universe” seemed to be the injunction he was either given or chose for himself to follow, so Thomas kinda just plopped the Eternals into the Asgardian side of things, as if the demigods had always been part of the MU. Logically, it works, saving Mr. Thomas a heckuva headache in trying to figure out just how to seamlessly integrate a group of characters never intended to be seamlessly integrated.

Others had different ideas, so it seems, meaning Marc Gruenwald and Ralph Macchio took the task of solidly slotting the Eternals into Marvel’s primary comic book universe, using a series of backup strips in What If-? to do so. These strips are a masterclass of continuity, and I can only imagine the fun Gruenwald and Macchio had in working through the various events they could tether the Celestials and their progeny to. I write this without knowing any other stories which focused on the Celestials, so to my understanding, these backup strips are the first time outside Thomas’ Thor epic where the Celestials are directly tethered to the creation of Earth-616’s humans, mutants, monsters, and superhumans.

For continuity buffs, these strips are highly entertaining and important. While they tell of the birth of the Eternals and the construction of Eternal society, they’re also connected to a whole host of other facets of the Marvel Universe. A group of Eternals break off from earth and head into deep space, where they encounter not only a towering Kree sentry but also descend upon Titan, the moon of Saturn, the implication being that from the Eternals will come the race that spawn Thanos and his brother Starfox, among others. Kree scientists dissect a fallen Eternal and pinpoint his origin to Earth, where they travel and conduct their own experiments, creating the Inhumans. Again, I couldn’t tell you if these events were originally connected, but if they weren’t, our writers have found a very valid “starting point” in the Eternals. The writing feels natural, the connections organic. It wouldn’t take a brain surgeon to read this and go “Oh, yeah, that makes sense!” The tethers are plausible, deepening the Marvel Universe and the Eternals’ connection to it. Gruenwald and Macchio construct their connections in such a way that fans could easily believe that the Eternals were always supposed to exist in Marvel’s comic universe, despite Kirby’s unconnected first series.

Much has changed since the Eternals last fought for the safety of the world with Thor. In the time between Thomas’ storyline and the narratives in this volume, both Starfox and Sersi, one of the Eternals, have joined the Avengers. Thus, we’re given a few stories that capitalize on the Eternals’ connection to our Western heroes. Roger Stern and Peter B. Gillis play with this idea in a couple of issues that see the Eternals become more known to out stalwart Avengers. Ample reference is made to Thomas’ Thor epic, making me grin as the writers readily acknowledged his work. A small gap seems to exist between Gillis’ Iron Man annual and Stern’s Avengers issues, meaning one particular plot point not shown in the annual becomes a simple implication in Stern’s arc. It’s a rather important development, and I was caught off-guard when Stern kinda offhandedly refers to something that should have either been visually depicted in his tale or Gillis’. Otherwise, the two tales mesh well together, showing how the Eternals are becoming more familiar with the world around them, even if that familiarity is occasionally involuntary.

You’re almost 200 pages into this volume by the time you reach Gillis’ twelve-issue Eternals limited series, their second after the cancellation of Kirby’s title. This was, for me, the main draw of the book. Though the ancillary material seemed appealing, I wasn’t quite sure how entertained I’d be by a handful of backup strips and a small selection of seemingly random Avengers issues. These issues turned out better than expected, but I was still excited for the Eternals series. Peter B. Gillis, and Sal “Why am I suddenly seeing this guy in every other story I review? (I’m not complaining he’s great)” Buscema craft a highly engaging follow up to both Kirby’s series and Thomas’ story. By this time, Kirby’s original intentions for the Eternals and their story--serving as a possible explanation for humanity’s creation--are gone, vaporized like Icarus’ wings. If Thomas put the lid on the coffin, Gillis nails it shut. Neither man seems all that interested in Kirby’s “myth as reality” concept, even if Gillis helps himself to a mythological or historical anecdote or two. What we get, then, is a more straightforward story: a proper Eternals sequel, narratively speaking.

Gillis addresses the Eternals’ place in superhuman society well, pulling them away from Thomas’ pantheons of gods and making them stand on their own. Gillis’ characters are firmly planted in the Marvel Universe, as references to various characters and past stories testify, but they aren’t overburdened by constant notations or anecdotes. I love it when creators tether their tales to other corners of the comic book world, but Gillis makes the right decision in keeping the main crux of his narrative away from most of the Marvel Universe. This is a standalone story, much like Kirby’s original series, benefiting from its varied relationships to books such as Avengers without bending a knee to the outside world. The Eternals here work in their own agency, on their own time.

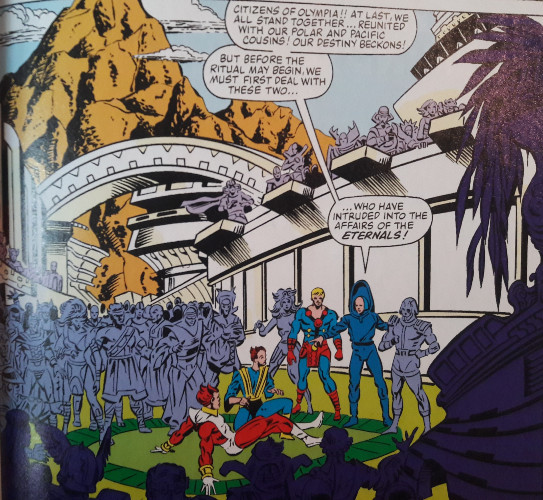

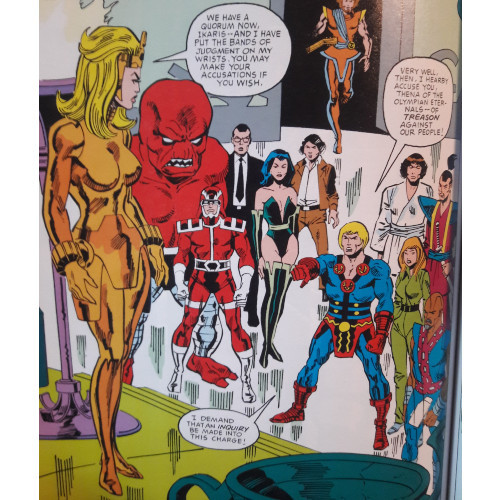

As a successor to a bygone era of Eternals tales, this story does a wonderful job continuing the arcs created by Kirby, Thomas, and others. Gillis wrestles with an important moment from Thor #300, the climax of Thomas’ “Celestial Saga”: the death of Zuras, king of the Eternals. A void must be filled, and Gillis toys with the concept beautifully as Zuras’ daughter Thena claims the throne, her rule challenged by the more-warlike Ikaris. The two squabble enough to make their conflict real, as Thena’s more moderate rule clashes with Ikaris’ notion of heroism and his grim outlook of their, eh, eternal enemy, the Deviants.

Deviant society itself is given a facelift under Gillis’ careful construction. He expands upon the world Kirby created, honing in on traditions and rituals while Buscema designs fantastic characters and settings. Gillis imbues the Deviant world with a real sense of structure and politics as, like his Eternals, characters clash over control and rule. Nicely, Gillis injects some moral grays into Kirby’s generally black-and-white world. Kirby’s Deviants were always the bad guys, the abhorrent villains, with little complexity outside their unique physical appearance. Gillis’ Deviants are more nuanced, their intentions for warfare deeper than “just because they’re EVIL.” He takes a concept Kirby introduced--the Deviant practice of eugenics--and enhances it, inserting a genuinely astonishing plot twist that reframes one’s perspective of Deviant society. The twist is well-done, teased appropriately before being unleashed on readers. It changes your perspective of Deviant society and reshapes a good chunk of the series itself.

Here and there exist other references to other narratives. Gillis runs with the Thena/Kro romance Kirby created in his series, using the Eternal/Deviant couple’s forbidden love to great effect in causing consternation and conflict. He also continues a plot thread Kirby “abandoned” and Thomas jumped on, the fate of the enigmatic Eternal, the Forgotten One. This particular thread, though interesting, feels included out of a sense of obligation, not necessarily because Gillis wanted to. “Kirby and Thomas used this character, so I might as well” seems to the pervading feeling towards the character. The Forgotten One adds conflict and intrigue to the tale but appears randomly, his narrative popping up in bits and pieces and not congealing until late in the series. I tended to become a little excited when he’d show up briefly, curious as to how Gillis would utilize his character, only to forget (how appropriate) and have my mind wander with other story elements until he showed up again.

Beholden as he is to the work of Kirby and Thomas, Gillis isn’t afraid to create characters and threads anew, leaving his own mark on the Eternals’ world. Main villain Ghaur is his most enduring creation, as the character’s continued use in crossover epic "Atlantis Attacks" and in Christopher Priest’s Black Panther series can attest. Ghaur (pronounced, I think, like “gore”) adds a new dimension to Deviant society, the high priesthood, allowing Gillis to capitalize on a warrior vs. religious acolyte theme. As a villain, Ghaur reaches heights Deviant characters like Kro and Brother Tode never could. Though Deviant society as presented by Gillis is far more nuanced, Ghaur’s intentions are shrouded in ignoble selfishness, presented as straight up villainous by series’ end. Wrapping himself in “for the people” rhetoric, Ghaur straddles the line between priest and power-mad monarch, his behind-the-scenes machinations clashing nicely with his public persona. He’s a complex villain, and I hope the upcoming Eternals film either uses him or at least references his character.

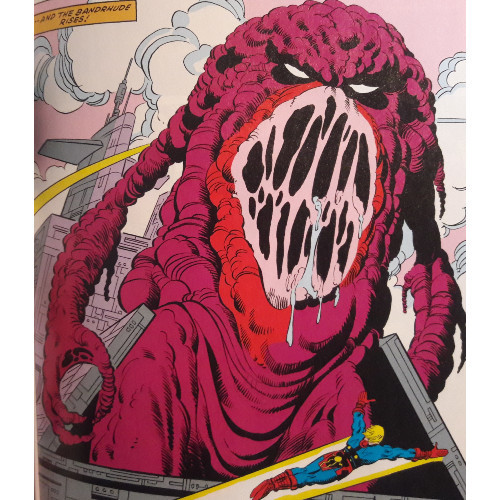

Gillis also delights in creating new Eternals and monsters. Characters such as Phastos and Kingo add new dynamics to the group--Phastos brings technological know-how and craftsmanship (in ancient times, he was believed to be Greek god Hephaestus) and Kingo offers a mastery of weapons, a significant contribution to action sequences when most of your characters simply fly around and shoot eye-lasers. New Deviant characters foment a rebellion that supports Kro and attempts to subvert Ghaur, giving more depth to Gillis’ Deviant society. The Bandrhude is a wonderfully designed yet ridiculously underused abomination sicced on the Eternals by the Deviants, showcasing a side of Deviant genetics that Gillis is unable to explore with any great depth. But these new pieces, for the most part, work in tandem with the old. Gillis is able to pay homage to the masters of the past while cementing himself as a creator who understands and appreciates the Eternals’ lasting influence.

This new Eternals series is the pride-and-joy of the volume, though the other, earlier pages shouldn’t be sniffed at either. This second series isn’t perfect--a few story beats feel a tad repetitive--but it’s by-and-large a winner. Marvel reigned supreme in the 80s, and I’m assuming that this series flew under the radar when stacked up against giants like Chris Claremont’s Uncanny X-Men, Frank Miller’s Daredevil, Walt Simsonson’s Mighty Thor, or Peter David’s Incredible Hulk. In hindsight, however, the positives are easy to see; Gillis’ story is polished fantastically by Sal Buscema’s artwork (a brief aerial/naval battle about halfway through the series is one of the best action set pieces I’ve see Buscema construct), and Gillis' own insights into Deviant society and the political scuffling with both the Deviants and Eternals deepen their place in the Marvel Universe. Roy Thomas may have dragged the Eternals into the Marvel Universe, but it’s Gillis, as well as Gruenwald and Macchio, who really take a long look at these superpowered stepchildren, open their arms wide, and greet the Eternals with a proud “Welcome home!”