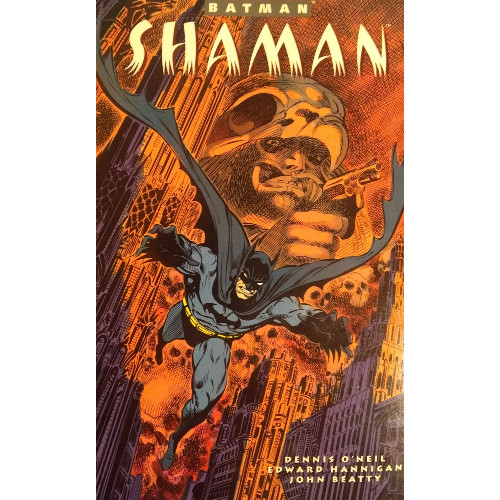

Distinguished Critique: Batman: Shaman Review

This "sequel" to "Year One" provides a somewhat disjointed mystery, the plot paling in comparison to its multifaceted masked hero

—by Nathan on May 8, 2025—

I've skipped around the Batman mythos lately, reviewing the pre-Crisis on Infinite Earths examination of the Dark Knight Detective's origin in The Untold Legends of Batman miniseries (DC's second-ever limited series), followed by a review of the first post-Crisis Jason Todd narratives. Today, I'm firmly planted on the post-Crisis side of Batman history (though I intend to skip back onto the other side in the future). It's been an interesting dance between these two eras of Batman. Where Untold Legends distilled various elements of the Batman mythos, creating a streamlined presentation of Batman's history, Frank Miller, in "Batman: Year One," updated the Dark Knight's origin, offering a Batman who was reliant on his street smarts and training, guided less by an over-dramatic promise sworn at the gravesite of his slain parents and more through a quietly pursued obsession.

Miller's impact on the character cannot be overstated, nor can his legacy on the last forty years of the character's history. What is interesting to note, however, is the immediacy of the impact Miller left on the vigilante. Miller's influence can certainly be felt in the ill-conceived "sequel" to his updated origin, "Batman: Year Two," but it can also be found in a series intent on capitalizing on the success of Tim Burton's 1989 Batman film. Launched as the third major Batman title, alongside Batman and Detective Comics, the same year Burton's film was released, Legends of the Dark Knight began as part of that "Year One" chronology, harkening back to the early exploits of Bruce Wayne's caped alter ego.

"Shaman"

Writer: Dennis O’Neil

Penciler: Ed Hannigan

Inker: John Beatty

Colorist: Richmond Lewis

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: Legends of the Dark Knight #1-5

Publication Dates: November 1989-March 1990

There is no denying Dennis O'Neil was a legend in the comics industry, developing several famous narratives for both Marvel and DC. My personal experience with his work is somewhat limited to a few stories, including a run on Daredevil which I (somewhat harshly) criticized (though I, hopefully fairly, primarily blamed it on the presentation of the volume I reviewed); a few issues of X-Men written after Roy Thomas and Neal Adams (a famed partner of O'Neil's) wrapped a run; and a few of his more famous DC contributions, including his and Adams' work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow, his Ra's al Ghul narratives (both his original work and later additions), and a small portion of his Question run. I'm not the biggest fan of O'Neil's Marvel work, though I am glad to have hit the highlights of his DC career, including his classic Batman and Lantern/Arrow material as well as those first strong issues of his take on the post-Crisis Question.

So I come into this volume knowing of O'Neil's prestige as a writer, specifically a DC writer, but with a somewhat divided view of his his style and how much I have appreciated his work. The scale leans towards the positive, but there is some counterweight. I'll also admit some trepidation in viewing this first arc as a "sequel" or at least a continuation of the work Miller did in "Year One." How could a writer hope to follow up such a story? Would they strive to fit Batman too tightly within the mold Miller poured and feel like a cheap knock-off of better work? Or would their interpretation be wildly different in an effort to stand out? I'm proud to report that, for the most part, O'Neil straddles the line, successfully positioning his Batman in the world Miller introduced while keeping the narrative and character from feeling derivative.

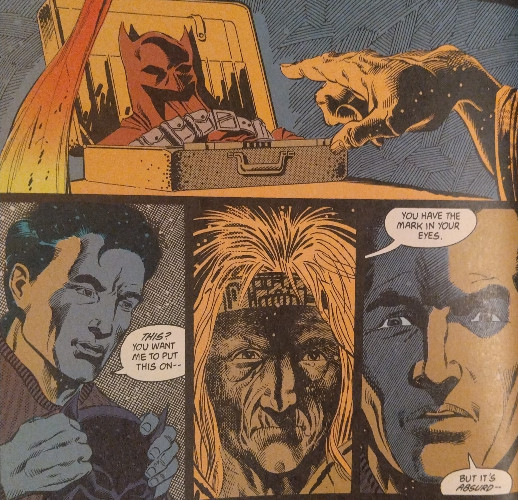

O'Neil is certainly indebted to Miller in several ways: his Batman is still grounded, prone to errors and injury, trying to determine for himself the kind of man he wishes to be. He apes two vital scenes from "Year One"–Bruce's first night out as a non-costumed vigilante and the moment he decides to become a bat. But these scenes come part way through the first issue, and O'Neil has decided the origin needs some additional "oomph," choosing to explore a period of Miller glossed over in his narrative. O'Neil winds the clock back a bit further, exploring an additional bit of inspiration before Bruce donned his trademark costume

We're given a very slight supernatural influence in Bruce's choice to become Batman, with O'Neil implying a story told to him by a shaman stuck in Bruce's brain. The bat through the window event is more of a confirmation for Bruce, that the story he was told influenced him correctly. The implication is that there is something originally inspired in Bruce, something existing after a near-fatal experience and his healing at the hands of a native Alaskan tribe. This isn't like J. Michael Straczynski's retcon of Spider-Man, where Peter Parker's origin was revealed to have mystic or totemic properties; Bruce is not suddenly connected to a larger "Bat-Web of Life" or anything. There is, perhaps, the smallest hint that what happens to Bruce is unknowable, a notion reinforced late in the narrative where Bruce briefly inhabits the "shaman" role of the title. Otherwise, the concept feels more mental than spiritual, that the lessons Bruce adapted from the story served him in a practical way.

I won't argue it's a bad layer to add atop Batman's updated origin. O'Neil is not dismissive of Miller's work, merely introducing an additional reflection point and surmising that Bruce's connection to bats is not a coincidental as past stories may have utilized or not even as simple as "Bruce fell into a cavern and became scared of bats and chose to use that fear against criminals." Is the addition necessary? No, there's not much need to thread in any extra ideas beyond the weaponizing fear piece–that already makes for a compelling character. But O'Neil uses the notion to imply a dichotomy between Bruce and the Batman. One important scene shows Bruce donning his bat-suit for the first time; sliding the mask over his face last, Bruce wraps his lips into a snarl and narrows his eyes. He is now someone else, someone other. He can be different than the billionaire orphan with this costume, embrace an identity previously unknown to him. He often threatens his enemies with physical harm, trouncing thugs. A darkness, a harder edge creeps into his voice and mannerisms. If there's any spell woven here, perhaps it's Bruce under the sway of the bat.

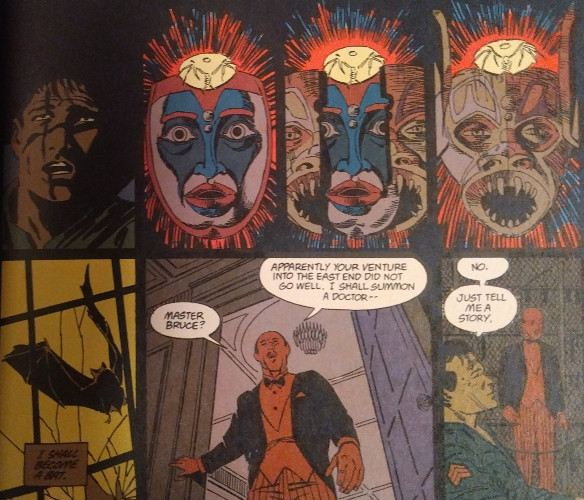

O'Neil implies an irresponsibility on Bruce's part in adopting this identity–interactions with Alfred point to the butler's concern over his employer's well-being; later scenes note a grievous mistake Bruce makes that has an impact on a whole town of indigenous inhabitants; Bruce himself perhaps begins to understands his predilection towards violence when he says he's not a doctor like his father. As the story reaches a final showdown between Batman and the narrative's primary adversary, Bruce enters a frame of mind which is more tactile, less aggressive. A second near-death experience leaves him, it seems, slightly wiser, better attuned to the right ways he should embrace the Batman identity.

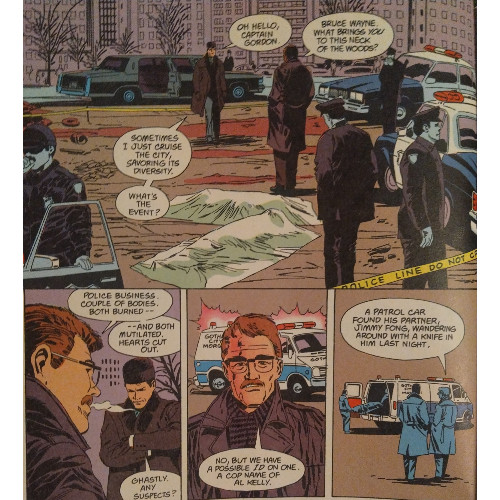

Around this narrative of masks and faces, O'Neil weaves a detective tale, complete with clues, fisticuffs, and a few twists late in the game. One of these twists is warranted, teased earlier in the narrative just enough to surprise the reader when a secret is revealed. The second is handled with less care, O'Neil becoming a bit lost in the later stages of the narrative and relying on the reader to mark a very, very minor moment as far more important than it originally appears. I had to flip back and find that moment to better understand its weight, and it still didn't click with me how we got from minor point A to major reveal B. O'Neil creates enough interest in the overarching plot that you want to keep following along to discern the mystery, but by time we reach the third act, he's lost some of that control. It's a shame this is where the plotting comes undone, because it's also by this point where Batman finds that confidence necessary to stop a madman from performing ritual sacrifices. We get a far more clever, thoughtful Dark Knight in the final pages, so watching the narrative unravel here is a bit of a disappointment.

What works well throughout these issues is the marvelous relationship O'Neil develops between Bruce and Alfred. Alfred is presented as very much the surrogate father/friend Bruce needs, supportive of his employer's one-man-war on crime while remaining cautious and critical, serving as the necessary voice of reason for this younger, more impetuous Batman. When Bruce suggests failure in this case could lead him to hanging up the cape, Alfred replies with uncertainty "whether that means I'm hoping for success or failure." Alfred is given the best lines, offering quips and wisdom in equal measure, subverting some of the narrative's violence and general propensity towards a grimmer tone.

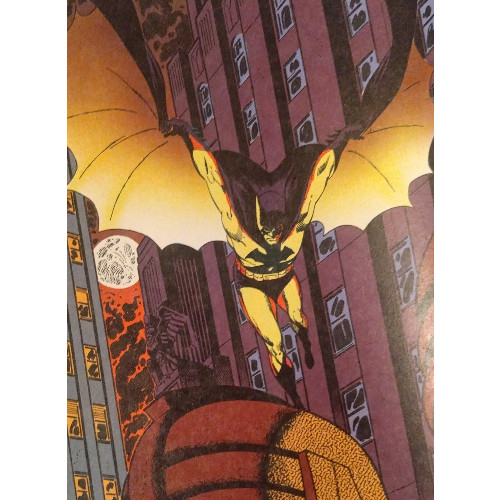

Ed Hannigan provides penciling which, when paired with Richmond Lewis' colors, feels very much at home within this "Year One" era of narratives. Much like the writing, Hannigan knows how to ape the atmosphere established by David Mazzuchelli while maintaining his own style. His work is cleaner than Mazzuchelli's, more defined. A brilliant early scene sees Bruce, during his first official night as Batman, stalk towards a group of armed thugs, backlit by street lights, Bruce walks out of the darkness, Hannigan revealing more of his visage as, panel by panel, this stalking shadow becomes a man, cape billowing around him like darkness. The cape, specifically, is a marvelous thing, fluid around Batman and used as much to intimidate as it is to keep the chill air away.

"Shaman" is a decent follow up to "Year One," a far better spiritual successor than the actual sequel delivered by Mike Barr, Alan Davis, and Todd McFarlane. It feels more aligned with the world Miller constructed, a worthy "sequel" in how it handles, develops, and advances its central character. O'Neil loses his footing a bit when it comes to the actual mystery at the heart of this tale–perhaps he became too enamored with the theming and characterization and lost his way. As a result, the mystery becomes a bit of a slog, harder to follow and less rewarding than it should be. But if you're willing to ignore that flaw, you'll certainly enjoy other pieces, whether it's the young vigilante learning to be a hero, the wise, white-gloved mentor who's also a friend, or the shadows out of which the Batman slides and glides to bring justice to a world in need of saving.