Distinguished Critique: The Question (vol. 1): Zen and Violence Review

An enticing recreation of an enigmatic character allows a master storyteller to bring the Question solidly into the post-Crisis DC Universe

—by Nathan on October 3, 2024—

Like many of the updated heroes whose 80s adventures we've been following lately, the faceless Question was given a facelift in the wake of Crisis on Infinite Earths, somewhat of a strange notion for a character often depicted as seemingly having no face at all. Unlike most other updated versions of classic DC characters, however, the Question began life under a very different comic publishing company.

Introduced in 1967 by Spider-Man and Doctor Strange co-creator Steve Ditko, the enigmatic Question was a Charlton Comics character who appeared in a feature included in Charlton's Blue Beetle comic. In 1985, DC acquired the rights to Charlton's characters, including Blue Beetle, the Question, Captain Atom, and Peacemaker, giving the Question his own series a few years following the devastating Crisis.

It's difficult to say, then, that the Question is a reboot. Though these first issues are certainly a "modern" reintroduction to the character, we're not discussing them as a rebirth of a previously published DC property. This isn't Frank Miller updating Batman's origin, George Perez injecting Greek mythology deep into Wonder Woman's veins, or Timothy Truman turning Katar Hol into a fascist space cop.

This actually makes my job today a little easier. I have found myself engaged with several of these post-Crisis reboots, yet unaware as I have been of the pre-Crisis versions of most of these characters, I haven't been able to weigh the rebooted versions against their prior selves. I've taken stories at face value, judged them for what they created rather than what they recreated. I won't need to worry about that here. There is no history to track (especially if I am correctly assuming Ditko's work on the character at Charlton didn't necessarily transition over to DC). I guess we look for fresh answers in this volume, which is fitting for a character called the Question.

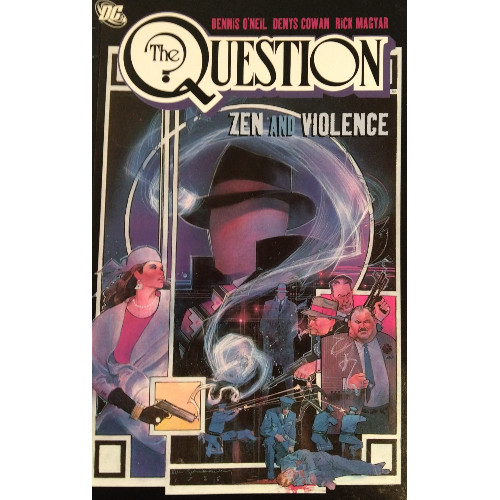

The Question (vol. 1): Zen and Violence

Writer: Dennis O’Neil

Penciler: Denys Cowan

Inker: Rick Magyar

Colorist: Tatjana Wood

Letterers: Gaspar Saladino and Albert DeGuzman

Issues: The Question #1-6

Publication Dates: February-July 1987

In the New Testament, Jesus Christ tells two different parables: one is of a Jewish man, beaten and left for dead on the side of the road, ignored by his peers but rescued by a Samaritan, the more likely individual to leave him where he is. The second story focuses on another man, having left home and taken his half of the inheritance from his father, squandering it and finding himself serving slop to pigs before returning to his father's home, where he is welcomed and embraced as one who was thought dead only to return alive. I don't mean to begin the review this way to say Dennis O'Neil has constructed a biblical parable in these pages, but both stories came to mind as I read these issues.

Investigative reporter Vic Sage lives a double life: by day, he reports the news, driving the point home hard that his hometown Hub City is a hotbed of political corruption; by night, he moves faceless in the shadows as a vigilante not too dissimilar from Will Eisner's The Spirit. Blue fedora, blue jacket, a tie, a mask to obscure his true identity. He's got the bit down. Vic walks a thin line in both of his lives, and much like the aforementioned Jewish traveler, is beset upon by thugs and left for dead, tossed into the drink. And much like the aforementioned Jewish traveler, he is rescued by an enemy and brought to safety, his memory a casualty of his ordeal.

Just as the reboot of the Question presents the character as a blank slate within the DC Universe, with no Charlton-crafted bulwarks against which prior continuity could be constructed, so is Vic Sage faceless in more ways than his mask. O'Neil (re)introduces us to a character lost, who must reclaim his purpose after losing the meaning he had. A relationship with a former coworker is made obsolete once she marries Hub City's mayor in Vic's absence. And Vic can kiss that cushy reporting job goodbye. A distinction is created between the Question before Vic's unfortunate swim and after: with his life as he knew it gone, Vic must become more intentional in his vigilantism. There are no more accolades, no strength of a news agency behind him. There is only the Question, a friend or two, and the mask he hides behind.

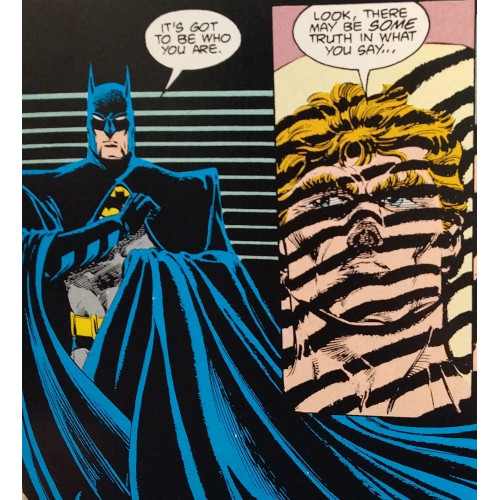

An interaction with Batman draws out those "Prodigal Son" parallels I referenced a few paragraphs ago. "You were getting kicks pretending to fight corruption," the Dark Knight Detective tells him. "When you felt like it. When you were bored. When your career needed a little boost. You can't half do what you were doing. It's got to be full-time–your need, your obsession, the engine that drives you. It's got to be who you are." There's a passing of the torch quality to the scene, except our author is extending it towards himself, as if O'Neil is drawing from the Batman he wrote in the 70s to shape this new character he's writing in the final years of the 80s. If anyone knows how to embrace obsession, it’s Batman, and O’Neil applies that same tenacity to the amnesia-stricken Sage.

Like the Prodigal Son, Sage has returned home, offered a second chance to do something with his life that's a little less self-serving. The costume and the name and the mask are all still the same, but Sage's intentions diverge. As a nameless, faceless Question, he could strike without care, strike without mercy, get his jollies out of fighting crime much more than hoping to uphold justice or make a difference. He's still nameless and faceless after his accident…but he doesn't need to live that way. There is weight to his actions, pure intentionality outside himself to drive him forward. His ego has been stripped away–in recovering the Question's mask, he must strip away the one he was wearing, that of "Vic Sage, crusading reporter."

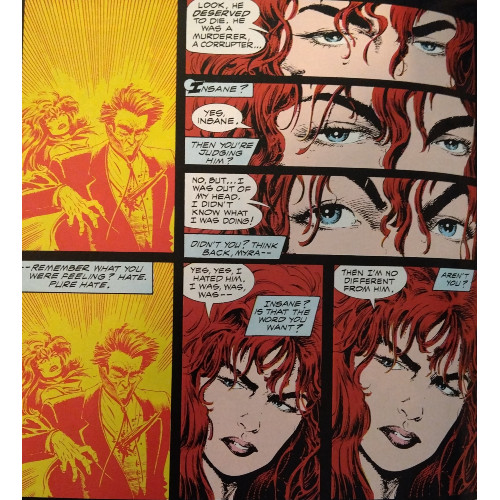

That moral heft glides through the rest of the volume. Sage's former love interest, Myra, is forced to make a horrifying decision late in the volume, spending the proceeding issue mired in guilt as she copes with the choice. A man, at the whims of his criminal father, attempts to blow up a bus full of schoolchildren as a way to impress his father and finally prove his worth. Another man acts indecently towards a coworker, staggering to the roof of his office building and wrestling with whether to throw his life away to keep from dealing with the guilt or confront his actions and change as a result. Like Sage, these characters are presented with questions of identity following a very specific focal point: their actions have led them here, wherever "here" is for any of them, and from "here," they must choose where to proceed. Forward, to life? Backward, to death?

This volume is surprisingly more thoughtful than I would have given it credit. Not that O'Neil was recognized as a poor writer or incapable of deriving depth from his storytelling. I have complained about his work on Daredevil, but I read only a portion of his total run (and, honestly, it's a huge endeavor picking up from Frank Miller). He cultivated some very socially conscious narratives in Green Lantern/Green Arrow with Neal Adams, and a kind of that mindset exists in this narrative. I would actually credit O'Neil with maturing in the intervening years–some of his older material was a tad blunt, but here, he allows his characters to do the heavy lifting to draw us into and out of the immoral morass that is Hub City. The corruption speaks for itself, as does the machinations of a mentally disturbed priest who serves as a Grima Wormtongue type to the mayor's King Theoden.

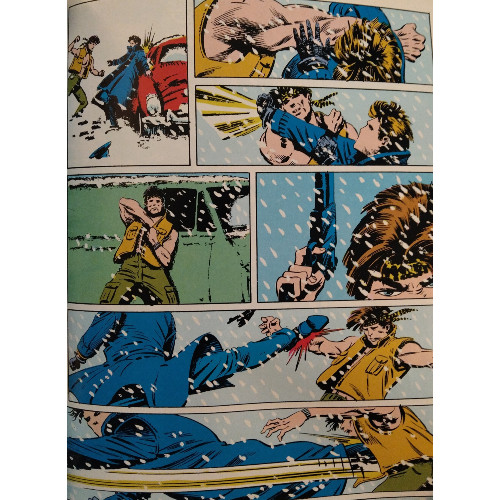

Denys Cowan provides plenty of grit in his penciling, not just in his subject matter, but in the sheer roughness of his art. This isn't the smooth, nicely colored and shaded material you'll find nowadays. Cowan's work never fails to cast a pall over the environment, whether through smoke, patchy linework, or shadows. Hub City is a dark place, and the Question isn't necessarily here to bring the hope and light a guy like Superman under John Byrne might readily offer the people of Metropolis. Scenes cast in rain and snow obscure the surroundings, leaving us in spaces that feel closed in, unknown, rough, and dirty.

Thematically, this volume ends up an engaging fray into the life and mind of a character I've never been too familiar with. O'Neil dials up the darkness in a way he may not have been able to in his 1970s Batman adventures. Again, hope is sparse, and the Question is less of a flashlight to guide the way and more of a hammer to break a hole through despair. I've picked up a few additional volumes which I hope to review at a later date. I'm still shifting through some post-Crisis recreations of characters, but with time, I hope to dive a little bit deeper into at least a few series I've already begun reading.