Distinguished Critique: Hawkworld Review

This series not only updates Hawkman but tells a stirring tale of resolve in the face of inequality and oppression

—by Nathan on December 11, 2023—

In my trips through post-Crisis on Infinite Earths updates on DC superheroes, I stumbled across a planet called Thanagar. I immediately bristled. If there's one thing I know about DC's resident winged hero–and it may be the only thing I do know–it's that the history of Hawkman (and fellow Thanagarian warrior Hawkgirl) is complicated.

Really complicated.

A while back, I tried reading through a HobbyDrama post on Reddit describing Hawkman's history, the ins and outs and retcons which continually befuddle(d) fans. I had a frustratingly difficult time following along and making sense of whether Hawkman was a human or an alien or why two different Hawkmen were around at the same time…ugh.

I'm acknowledging the confusion so I don’t need to acknowledge it further.

I assume Hawkworld, which started as a post-Crisis, three-issue limited series before developing into an ongoing series, added to the confusion. However, simultaneously, it seems to be the most frequently mentioned post-Crisis introduction to the character I could find. So I'm pushing all retcons and additional histories out of the nest and letting them fly away–bye-bye, see ya, don't come back.

I'm just here for the limited series. I want to see how Hawkworld, divorced from the continuity I don't understand, flies alone. By its own merit, we shall see if it soars like an eagle into a cloudless, blue sky…or flops on its stomach in the water like a penguin vainly flapping its wings.

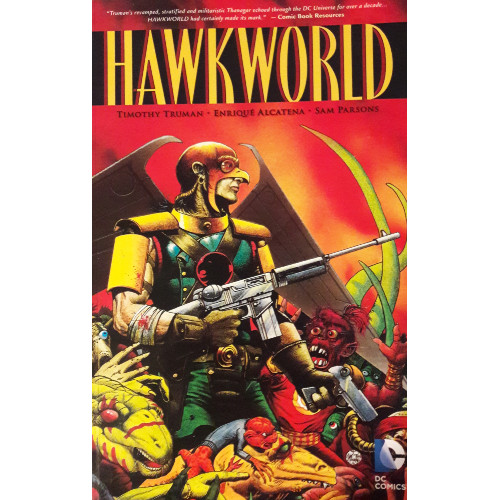

Hawkworld

Writer: Timothy Truman

Penciler: Timothy Truman

Inker: Enrique Alcatena

Colorist: Sam Parsons

Letterer: Tim Harkins

Issues: Hawkworld #1-3

Issue Publication Dates: August-October 1989

I assume some of my appreciation for Hawkworld would be heightened were I aware of Hawkman's history prior to 1989, similarly to how my interest in Mike Grell's Longbow Hunters centered around how the writer/penciler distinguished Oliver Queen from the pre-Crisis Green Arrow and his gimmicky projectiles. Fortunately, my inability to compare and contrast Hawkmen didn’t impair my enjoyment of this three-issue series.

Hawkworld stands out as a very fine introduction to a DC character I am aware of but have rarely read. The series contains a level of depth and brutality which seems representative of the era, and alongside Longbow Hunters, "Batman: Year One," or even Watchmen, works well within its complex context of violence, cruelty, corruption, and social commentary. I recently berated Mike Baron and William Messner-Loebs' Flash for trying to incorporate unnecessary darker material, but Truman's re-framing of the Hawkman character allows for the grit and grime to show through powerfully.

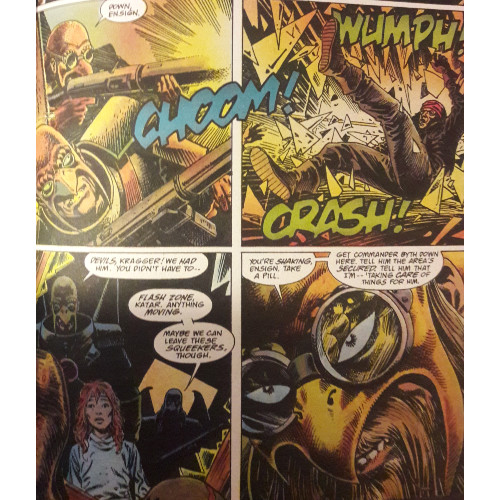

Katar Hol, a recent recruit to the Thanagarian police force, witnesses firsthand the dismal living conditions and police brutality lower classes endure on his home planet. These people, brought in from planets Thanagar has conquered, suffer under the boots of their masters, kept in slums literally beneath the Thangarian palatial high rises. Thanagar is imagined as a world not unlike Marvel’s Nueva York of 2099, where the ghetto-esque Downtown serves as the "old New York" the future world was constructed atop. Likewise, conquered races are subject to harsh Thanagar rule, brought in as slaves and servants, only allowed above the clouds for menial work and to watch the planet appropriate their cultures.

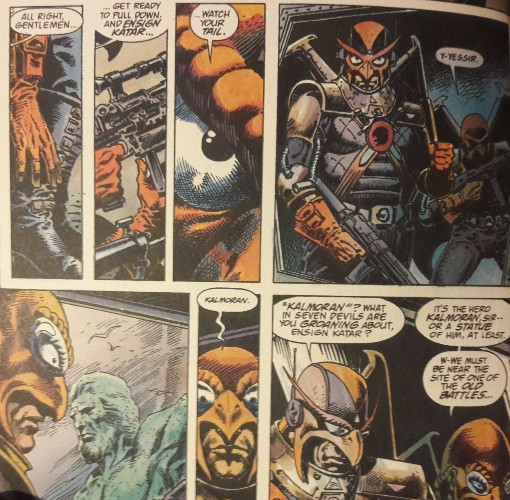

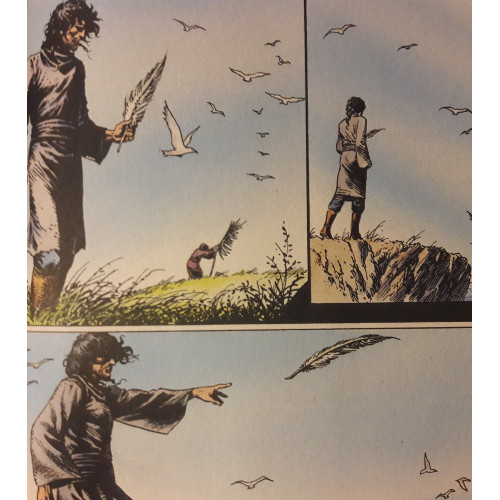

Though Katar is stirred by this treatment, he is simultaneously put off by Thanagar's loss of its own culture. By usurping the art and food and cloth of other worlds, Thanagar, to Katar, has forgotten its own identity, becoming a mishmash of ideas and worlds. The only new products they seem to invent are drugs. Katar clings to old history, admiring an ancient hero and fondly looking upon a past he didn't live. Though born into luxury and seemingly destined for political aspirations–his father is the renowned scientist who developed their winged technology–Katar elects to get into the muck and the grime of the underworld, intentionally divorcing himself from his heritage.

Truman nicely weaves in these notions of social commentary, speaking on racial conflict, police brutality, and government oppression through an allegorical lens. He develops his ideas well and writes in ways which readers will readily apply the narrative to their own lives and circumstances. You don't need someone to spell out for you why a race of white, humanoid aliens conquering seemingly lesser creatures and demanding these creatures serve them to see the allegory. A young, upper class woman berating and kicking a waiter from another planet in the head after bumping into him is painful to observe no matter the races or genders of the characters. Her entitlement is made clear in the moment, shockingly brutal yet implicitly tethered into her upbringing, a sense of self and perspective of others unlike her developed by her status.

Though it's never heavy-handed in a preachy sense, Truman can occasionally force the savagery focused on these other races–a scene where Katar and the aforementioned red-haired woman go on a "safari" of sorts where Katar’s companion shoots four ape-like aliens feels brutally on the nose. We’ve already witnessed police brutality and servants being harangued–an upper class individual shooting an alien for fun feels a tad over-the-top.

If this was all Hawkworld was–a treatise on class division or imperialism by showcasing repeated offenses conducted against alien races–it would grow stale and boring quickly. Fortunately, Truman's narrative resonates more deeply through Katar, as we witness his own struggles against the predatory nature of his people. About halfway through, a twist alters the trajectory of Katar's destiny, placing him in a position where he is better aligned with these subservient extraterrestrials and allowing him the impetus for growth when he no longer hides behind the veils of customs and courtesy. The true Katar Hol may show himself.

You cannot call the series one-of-a-kind. "Character realizes the horrors of their society and strives to break from it" is a staple in dystopian fiction, from 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 all the way through Hunger Games and Divergent. And it's an idea not confined to popular fiction. The Dark Knight Returns, Old Man Logan, and V for Vendetta all feature heroes seeking to alter the state of their world, subjected to corrupt ruling classes or crawling from the wreckage of war. Truman should be applauded, however, for not making Katar the starry-eyed waif who sees poverty, destitution, and horror far later than he should or has an inordinate amount of faith in the government that is broken down over time. He's no dummy, not lost to the dregs of drug-induced sleepwalking like several of his compatriots. From the start, we get the sense Katar has seen the cracks; as the series progresses, he simply chooses to pick away at the crevice and broaden his understanding of his world's brokenness.

Truman illustrates Hawkworld as well as writes, commanding the structure and scale of the world he develops. Creatures are crafted uniquely; his underworld setting is as damp and dark as his upscale world is bright, shimmering in the sun; wordless sequences focus your gaze on individual panels as Truman progresses the story beat by beat, panel by panel. His is a militaristic Thanagar, with sharp edges and symbolism guiding the looks of settings and outfits.

A twist near the narrative's end heightens the series beyond its already admirable quality, creating a compelling sense of catharsis unknowingly sewn earlier. I will skip details, but it points to the depth Truman anchors in the series. I don't think I can ever consider myself a Hawkman fan (but we shall see how the future tests that assertion), but call me a fan of Hawkworld. It’s a brilliant re-imagining of a classic character, and if we ignore the convoluted history this series may have wrinkled further, it stands alone as a powerful post-Crisis reintroduction that, unfortunately, doesn't seem to be as widely discussed as "Year One" or Man of Steel but deserves recognition nonetheless.