Distinguished Critique: The Flash: Savage Velocity Review

In updating the Flash legacy for the post-Crisis DC Universe, this volume is a misguided introduction to Wally West

—by Nathan on December 6, 2023—

His name was Barry Allen. And he was the fastest man alive.

For years, the red-garbed guardian had raced through city streets, protecting citizens against the machinations of men with cold guns, mirror guns, trick boomerangs, and weather wands. But when a crisis threatened all reality (and every reality), Barry Allen ran faster than he ever ran before, sacrificing his life to help stop the Anti-Monitor.

For a time. He'd come back. They always come back.

But for several decades, old Flasharino was dead, disintegrated into space dust. This meant his young nephew, Wally West, would need to ditch the "Kid" from his old moniker (along with the yellow spandex) and grow up a little bit. The world needed a Flash…

…it's kinda a shame we got stuck with this guy.

The Flash: Savage Velocity

Writers: Mike Baron, William Messner-Loebs

Pencilers: Jackson Guice, Mike Collins, Greg LaRocque

Inkers: Larry Mahlstedt, Jack Torrance, Romeo Tanghal, Tim Dzon

Colorists: Carl Gafford, Michele Wolfman, Shelley Eiber, Nansi Hoolahan

Letterer: Steve Haynie

Issues: Flash #1-18, Flash Annual #1

Issue Publication Dates: June 1987-November 1988

Before you rip my head off at the speed of light for the above statement, let me be clear: Wally West is a great Flash. I've enjoyed what I've read of Mark Waid’s run, and I remember enjoying the pieces I read of Geoff Johns' run a long while ago (the latter I've since collected in its entirety but have yet to delve into). I've stated before that the Flash is probably my second favorite DC character, despite my limited exposure to the hero's adventures.

But this is a rough beginning for the character. The starting gun fires, and though he's entrusted with running a marathon, Wally bursts off the starting blocks with a bit of a limp.

Unlike compatriots Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, or Green Arrow, Wally isn't really given an updated origin or facelift of some kind…not really. What Wally is thrust into is the burden of increased responsibility following the death of his uncle Barry. He's twenty years old, and he's handed the keys to the Flash legacy. He's got to wear the suit, use the name, make proud his uncle's memory. Where Man of Steel or Emerald Dawn is focused on reestablishing characters and having them redefine their first steps as superheroes, Wally is faced with carrying his uncle's legacy rather than carving his own. Unfortunately, beyond that basic premise, Mike Baron and William Messner-Loebs don't really seem to know what to do with the guy.

I get the struggle the writers create for Wally: he's young, somewhat naive, perhaps a tad irresponsible and given over to youthful tendencies and attitudes. He's barely beyond his teenage years, and for the first time, he's been graced with a superhero identity that doesn't relegate him to the status of a sidekick or constantly remind him he's a kid. It's like if Dick Grayson replaced Bruce Wayne as Batman without ever becoming Nightwing, donning the Dark Knight's cape and cowl with only some experience as Robin under his utility belt. Unlike Dick's transition from Robin to Nightwing, Wally is immediately thrust into the role of his former mentor. He's not given the opportunity to grow up a little, define his own identity. He assumes the mantle of another man and keeps running forward. No pit stops, no looking back.

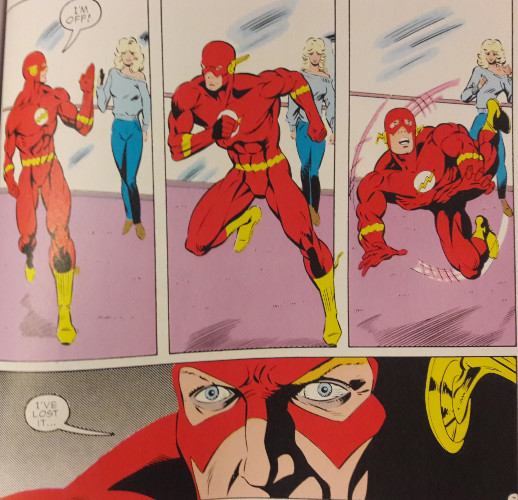

There's a sense lingering through this volume that maybe, maybe, Wally isn't quite ready for the job, that his youth, combined with his impulsiveness, detract from his ability to fit into the Flash boots snugly. And though the writers are wise enough to not pound the idea into your brain, they leave it so ambiguous that you start to wonder if the theme is intentional at all. Wally gets into a brief shouting match with his dad over his title, insisting he's no longer Kid Flash, and we periodically receive some small reflections on Barry's legacy throughout these issues. Wally's in this weird place where maybe he doesn't want to admit his naivety, focusing instead on doing whatever he can to honor his uncle's legacy, regardless of whether or not he's in the proper place to do so. Again, he's skipped over a transitional phase, diving right in without the proper support or training.

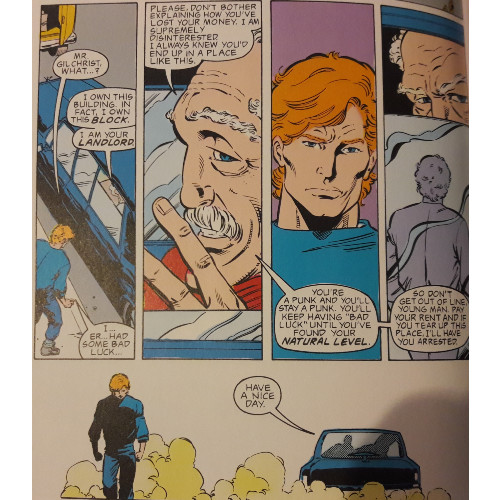

Baron in particular hones in on this youthful quality Wally displays, making this new Fastest Man Alive little more than a petulant man-child at moments and largely divorcing him from that struggle. Wally wins the lottery and becomes temporarily flush with wealth, growing angry with people attempting to feed off his newfound fortunes and picking fights with government officials who wish to regulate his lavish lifestyle (that he's a publicly known superhero whose superhuman escapades often lead to property damage only incite complaints against him). He dates a married woman older than him, even fighting her estranged husband after he gains abilities of his own. And he flirts with other women even while working through his already complicated relationship.

Again, it's difficult to read if this intentional on Baron's part–is Wally supposed to be this irresponsible? I'm all for heroes who make mistakes, and as a Spider-Man fan, I can kind of understand writers reinforcing the "With great power..." theme with a hero repeatedly (though, in Spidey's case, it does feel less warranted over time). But simultaneously, you expect Wally to own up to some of these dumb endeavors, and he rarely does. Hence why the "Wally is an irresponsible young punk who needs to grow up a little" feels ambiguous at times.

Messner-Loebs, who begins writing with issue #15, does seem to want to bring Wally back from the brink–it's telling his first issue is titled "Hitting Bottom," acknowledging the state Wally has found himself in. And, to his credit, Messner-Loebs more directly references Wally's recent outlook on life through the voices of some other characters, words of wisdom we've sorely missed in the last 14 issues. Wally's selfish, impetuous demeanor is presented as more of a struggle, something Wally deeply knows is wrong. He's presented as a young man clinging to his own views and desires as the right thing, even though he understands change is necessary. "Struggle" is what we see in the last few issues, something lacking in Baron's narratives, which breeze by as if all is right with the world.

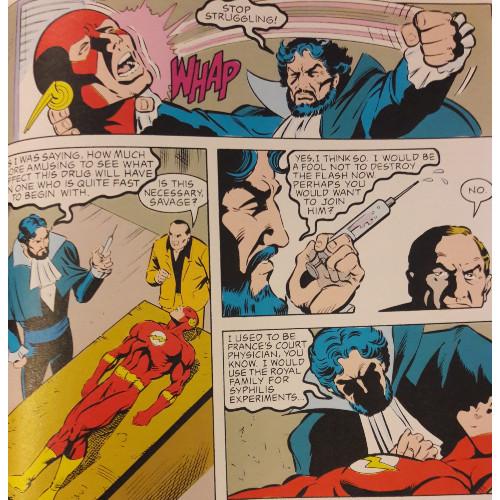

And what a world we enter: on the superhuman side of the scale, Baron and Messner-Loebs both pick up speed. Baron in particular wonderfully toys with Wally's abilities, having him run cross-country in the first issue, speeding by cities and through states between heartbeats, pushing the young man's capabilities. Fun concepts are strewn throughout the book–a delivery service headed up by some other speed-endowed characters; a fantasy-esque sequence in a world characters are sucked into by a guy who's essentially a walking black hole; Vandal Savage trying his hand as a, uh, a drug dealer…okay, that one’s a little weird for a millenia-old warlord. Baron and Messner-Loebs generally stray away from classic Flash foes, giving Wally new enemies to combat and trying their hand at imaginative characters. It's a new world, why not explore it a little? Why not throw it some new villains to establish a different kind of rogues gallery for Wally? There's no reason he needs to always trounce the same thugs his uncle fought.

Wally's world is fairly self-contained–you don’t really see Superman or Batman pop up aside from a few panels. Flash does become briefly entangled in Millennium, the DC crossover epic of 1988. A fairly important subplot is woven through a handful of issues, and though the logistics are a tad wonky, Baron at least tries incorporating some of the themes he's been sewing into the primary conflict nurtured by Wally's involvement in this crossover. In reviewing Millennium, I discussed how incomplete it felt, largely because of the tie-in issues strewn throughout a host of other series. Funnily, The Flash doesn’t shed too deep a light on the happenings of that event, offering a brief glimpse into Wally's highly personal relationship to the crossover before slipping back into its mode of storytelling and relegating the conflict nicely created in one issue to a handful of comments made elsewhere.

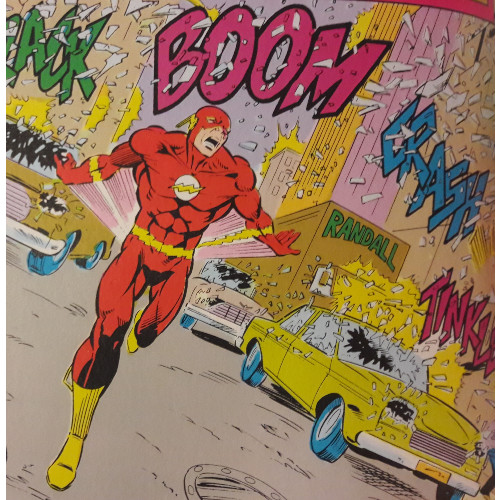

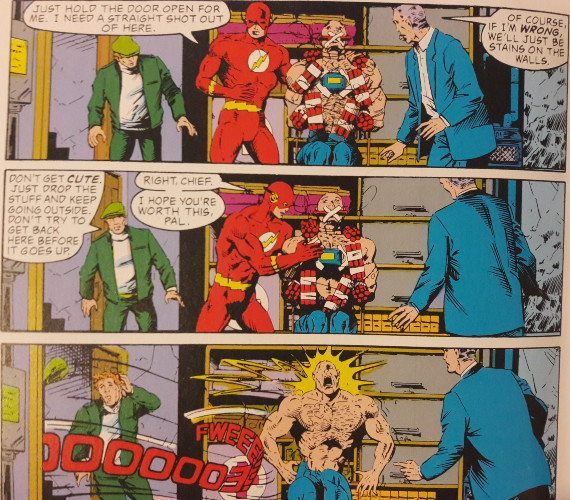

Darkness is surprisingly prevalent in these issues, loping around the pages like some snarling predator, seeking pieces of light to clamp its jaws around. There's a consistent attempt, saddled alongside Wally's youthful attitude, to inject some grim atmospheres into the book. Maybe it's to help make sense of Wally's place in the world, to try and force him to grow out of this childish stint he's in, but the darkness feels misplaced, particularly as Baron specifically fails to showcase Wally's youthful errors as mistakes which need fixing. Several folks are killed by a rampaging AI called Killg%re which takes on a sentient form resembling a metallic sandworm from Dune; Wally saves a guy with dynamite coiled around him by barbed wire; a woman is beaten by her husband.

I don’t know if this tonal shift was intended to mirror changes happening with other characters–Batman became progressively darker thanks primarily to Frank Miller; Green Arrow traded in his boxing glove arrows for sharp shafts which pierced hands and knees; the Suicide Squad was predicated on characters who could get killed at any moment. "Let’s make the Flash dark too," someone at DC may have intoned at one point. It's a mistake. Yes, the point is to make Wally different from his predecessor and somewhat more relatable to the audience–look at this, Wally deals with problems just like all you readers! But that's not the point of the character. I get when change is necessary, and I understand the wish to make Wally different from Barry…but the ways our writers put Wally through the wringer don't feel like the right method. The darkness doesn't showcase Wally's unbreakable spirit or ability to triumph against increasingly bleak odds. Saving a dude with dynamite strapped to him doesn't prove Wally's heroism any more than if he pulled kids out a burning fire. It's just a more shocking development to ratchet up the bleakness of your superhero comic.

I did some research into reading orders for Flash comics, and in several instances, I could not find any volumes after Savage Velocity collecting issues until the start of Mark Waid's run, which began with issue #62. One website I perused summed up the possible reason better than I could: "This period [between #18 and #62] is uncollected and mostly never discussed." Though I enjoyed the final Messner-Loebs issues over the Baron narratives, I can't say I liked them by a lot; given Messner-Loebs stayed on the character until Waid took over, and given the general acclaim surrounding Waid's run, it's easy to see why these in-between issues have never been collected. You can probably find them in your back issue bins. For me, they'll stay there.

Like I said at the start, this is a rocky road for Wally West to begin his career as the (non-Kid) Flash. There's certainly an attempt to locate his niche, to have him break out of the sidekick status he remained in for years. Baron and Messner-Loebs want us to better understand Wally as a character–young, mistake-prone, with lots of room to grow. Problem is, Wally runs by all those issues and fails to recognize that need himself. Maybe he's moving so fast he misses the signs others can easily see in front of him.