Distinguished Critique: Camelot 3000 Review

This highly imaginative series blends legend with science fiction, a unique combination somewhat hindered by sidelined characters

—by Nathan on January 5, 2024—

Back during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tripwire Magazine released a series of reviews detailing "The 100 Graphic Novels You Should Read While Stuck Inside." As someone who was stuck inside (even relatively briefly), I scanned the list, looking for some good stories to peruse while lounging on my intermittent, forced periods of "vacation." I found myself nodding in agreement over several of Tripwire's choices–The Dark Knight Returns, "Batman Year One," Walt Simonson's run on Thor, Darwyn Cooke's New Frontier–and mentally marking other stories I had not yet read.

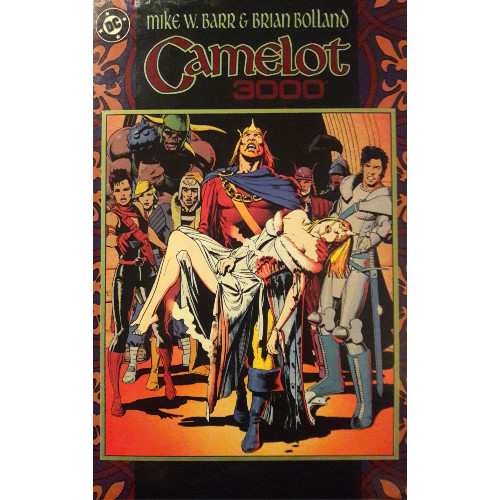

One of those narratives I noted was Mike W. Barr and Brian Bolland's Camelot 3000. Bolland I knew as the illustrator of The Killing Joke; Barr I was unfamiliar with (and would remain so until reading "Batman: Year Two"). I took a few days to read a digital copy of Camelot 3000 and walked away from the experience…relatively unchanged. I wasn't wowed. The art was great, but I didn't feel particularly endeared to the narrative or the characters. It was kinda how I processed Watchmen: fantastic illustrations, great world-building, but I struggled to get behind the story.

But for whatever reason, my brain kept coming back to it. Other stories don't float through my brain randomly without reason. Looking at my shelves, I can honestly tell you I don't occasionally think about, for example, Frank Miller and John Romita Jr.'s Man Without Fear limited series (even though it's a great series) or Chris Claremont's Uncanny X-Men run (even though it’s a great run) unless I happen to spot those volumes, stumble across an article or review, or bring them up during a discussion. I've got stories I really, really enjoy that don't just periodically pop in for a visit. But Camelot 3000 kept coming back, usually followed by a Maybe I should read that again.

So when I came across a ridiculously low priced copy of an older trade paperback in a used book store recently, I picked it up (same day I picked up "Year Two" coincidentally). And I read it again. Since I last reviewed "Year Two" for this series, I thought jumping back into Camelot 3000 to explore its inner workings was appropriate.

Camelot 3000

Writer: Mike W. Barr

Penciler: Brian Bolland

Inkers: Bruce D. Patterson, Dick Giordano, Terry Austin

Colorists: Tatjana Wood

Letterers: John Costanza, John Sinclair

Issues: Camelot 3000 #1-12

Publication Dates: December 1982-April 1983, July 1983-September 1983, December 1983, March 1984, July 1984, April 1985

Hear ye, hear ye! The king has returned!

I'm not super familiar with the legend of King Arthur, in any of its variations. I read a version of Sir Gawain and Green Knight in high school. I saw the Legend of the Sword movie directed by Guy Ritchie. The version I'm most familiar with is the guy from Monty Python and the Holy Grail who rides around on an invisible horse whose hooves are simulated by the clapping together of coconuts. I'm not a scholar, in short. I'm aware of certain classic elements–the sword from the stone, the round table and its knights, Camelot, the lady of the lake–but I cannot spell out how the legend has changed and been adapted over the centuries.

I think you'd be hard pressed, however, to find anyone who placed King Arthur in the year 3000 before Mike Barr and Brian Bolland.

The conceit hooks you immediately, from either the title or any snippet of premise you can latch onto before reading the series. Medieval knights thrust into the future? Men with swords set against aliens with lasers? Magic and mythology versus science? It's a brave new world for the Arthur of antiquity to conquer.

I first read this series three years ago and, as noted in the introduction, walked away unscathed. Not overwhelmed with praise, not overcome with complaints. More recently, I had taken a look at Barr's "Year Two" and stepped away from that experience with a sour taste in my mouth. Barr carelessly left symbolism scattered across the streets of Gotham so thick you practically choked on it. His ideas were bombastic and bizarre, worth exploring yet executed awkwardly. I wondered if I had just ignored or overlooked similar problems with Camelot 3000.

The answer is largely no.

Let's not give Barr a dragon's hoard of credit here: some of what works well in the series can be found in what Barr combs from the original Arthurian legends. Story beats and characters are already present. This is, in a certain sense, a sequel to stories told centuries ago. Arthur awakens, already a warrior king. He soon awakens his knights and queen, similarly familiar with their own prowess and knowledge. This is more of a Dark Knight Returns-style story, of yesterday's heroes stepping anew into a modern age and realizing they are sorely out of place while simultaneously serving as the legends humanity desperately needs.

Even as a reader not thoroughly aware of the original King Arthur myth or its historical context, I can easily see how cleverly Barr weaves in elements of the legend throughout his narrative. Excalibur, the stone, the lady in the lake, and Merlin are featured heavily, generally placed within a developing context and feeling properly placed in this strange future world. Occasionally, Barr's creativity feels hampered by serving the original myths–though the Holy Grail is eventually woven cleverly into the futuristic context, its initial appearance comes late in the series and feels somewhat wedged into the plot because it's just so important to include. Barr doesn't often offer context for exactly why Arthurian elements appear when or where they do–we don't discover, for example, why exactly King Arthur is still alive all these centuries later–but you're never left frustrated by this circumvention. Again, if readers are interested in "the Knights of the Round Table versus space aliens," Barr's already won half the battle by grabbing their attention.

The other half is maintaining reader interest, and Barr does a decent, though imperfect, job. Our central protagonists are outlined fairly quickly–King Arthur, Sir Lancelot, Queen Guinevere, Tom Prentiss (who stumbles upon the century-sleeping monarch), and Sir Tristan–and Barr focuses his narrative through them. A love triangle established between the king, queen, and Lancelot encompasses much of the character development, offering some engaging drama and themes of trust and struggle. Noble as he is, Arthur is still given over to passionate outbursts of anger and authority, offering him a multi-sided character whose greatest intentions are threatened by internal insecurity. If you're a fan of Chris Claremont's Cyclops/Phoenix/Wolverine debacle of the late 70s and early 80s, you might appreciate the consistent dramatic elements sewn between characters forced to work together and trust one another who still come to blows over unbridled tempers.

Tom is our "everyman," someone Arthur owes his newfound existence to and an honorary member of the Round Table. He's the driving force through a good chunk of the story, and until Barr devalues him by turning him into a lovesick puppy dog, Tom does well as a representative of the reader. He's not special–no training, no magic–yet upon his intervention rests the fate of the world. As noted, Barr handles him worse as the series progresses, but for a time, Tom is staunch and brave, a loyal follower as willing to lay his life down for his king as the other assembled knights.

As our primary protagonists are made clear quickly, we soon discover those "other assembled knights" are given short shrift. Both Barr and Bolland attempt to squeeze as much diversity and visual creativity out of them–Sir Percival is imagined as a hulking "Neo-Man," Sir Kay as a roguish crook, Galahad as a samurai warrior. Despite each character's unique appearance, none are given as deep characterization as the heroes Barr has already offered center stage. Sir Gawain is re-imagined as a father seemingly abandoning his family, yet save for a small handful of scenes, the conflict created by his leaving is given little space. Kay's role is played up as comic relief, despite his importance as Arthur's brother. Galahad, despite some familial connections of his own, is used just as sparingly. The seeds of unique conflict and characterization are sewn; they're just not watered as often and, as a result, don't grow much.

Of the knights, Tristan is offered the most depth–in a shocking move for a comic in the early 80s, Tristan is re-imagined as a woman named Amber and thus becomes embroiled in internal conflict regarding this gender swap. Barr's comments on the whole subplot are meaty, offering Tristan depth neglected other characters, yet writes his/her turmoil in a way some may find concerning nowadays. And if that weren't enough, Barr compounds the issue with a subplot involving a former fiancee and a current beau. I tend to not get political or wax poetic on social commentary, preferring to ignore potential heated discussions. What I will say is this: from Tristan, Barr pulls out the character of someone not who they want to be, haunted by the hole they feel inside of them. Regardless of where you lie on the scale of gender politics, you would do well to at least recognize the more universal traits found within Tristan's narrative.

All of this wizardry and wonder is illustrated masterfully by Bolland, who painstakingly labors over each panel…and for good reason. Though DC had published a few shorter limited series, Camelot 3000 was their first maxi-series, published shortly after Marvel released their own first-ever limited series, Contest of Champions. This is an occasion for which only the highest of styles will suffice, and Bolland responds admirably, pouring detail into each figure present. Close-ups of faces are particularly realistic, with eyes and brows wrinkling and displaying true emotions. Note, if you will, the sliding publication dates of the issues as outlined above–there's a reason why deadlines were missed. Bolland's attention to detail, perhaps somewhat aggravating to the issue-by-issue consumer between 1982 and 1985, is to be highly praised in hindsight or for the reader capable of reading through the trade paperback in a sitting or two.

This isn't a perfect series, and if we're being honest, much of the groundwork for the good in Camelot 3000 was laid several hundred years before the creative folks involved were even born. Barr wonderfully infuses his Bolland-built future with medieval mythology, pulling from older narratives to construct something new. It's a very unique premise, and the creators often handle the material well. Perhaps because Barr and Bolland are so steeped in the lore and working to wrangle a new angle from the mythology, we are left with some flat characters. But maybe that's what knights are supposed to do: step aside so their king can shine brightly for the world to see.