Distinguished Critique: Legends Review

DC's first post-Crisis event fumbles its primary conceit, a cool concept and great art sacrificed on the altar of heavy-handed dialogue

—by Nathan on September 26, 2023—

A little over half a year after DC fundamentally altered their universe with the twelve-part epic Crisis on Infinite Earths, the company produced its first post-Crisis crossover: Legends. This six-part series (excluding the tie-in issues, which expands this narrative to 22 chapters total) intended to set the tone of the DC Universe moving forward post-Crisis. It’s a new world in need of new heroes, and with this series, DC gave themselves the opportunity to establish a new status quo in a couple of different areas.

The premise feels directly taken from the biblical book of Job: the Phantom Stranger and Darkseid of Apokolips make a deal to test the morals of Earth’s heroes. Darkseid pulls strings and sends agents to sow discord and hate amongst the populace, with the Stranger supporting the efforts of the Justice League, Superman, Batman, and others to overcome whatever evil the lord of Apokolips throws their way.

Will our heroes falter under the weight of a world turned against them? Or will they strive against fear-fraught fanaticism and prove themselves…

Well, you know.

Legends

Writers: John Ostrander (plotter), Len Wein (scripter)

Penciler: John Byrne

Inker: Karl Kesel

Colorists: Tom Ziuko, Carl Gafford

Letterer: Steve Haynie

Issues: Legends #1-6

Publication Dates: November 1986-May 1987

Note: save for some minor edits, this blog is the same as it was when I originally posted it to Hubpages

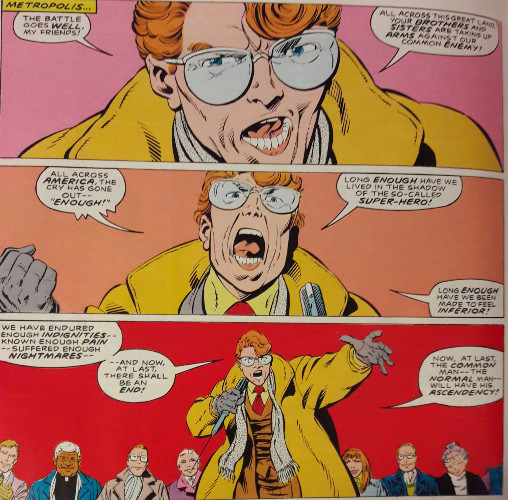

The word "legends" works its way so often into this series, not even counting the covers or splash panels, you’d need to be paying very little attention to think Ostrander and Wein weren’t trying to be philosophical. A very forced sense of depth weaves throughout the entire series, with this concept of "legends" hammered forcefully into the reader’s skull across each chapter. Darkseid’s plot hinges on the term–by turning Earth's populace against their heroes through the words of his agent Glorious Godfrey, the lord of Apokolips intends on removing all faith in these "legends" by which and replacing their mythos with his own.

The plot is confusing from the jump, as Darkseid never fully explains how he intends on doing this outside of Godfrey’s hypnotic abilities. You get the sense he’ll transform Earth into just another Apokolips, a dark husk of a planet eternally ruled by his iron fist, but anything post-Godfrey is implied or opaquely discussed. The plot also completely hinges on Godfrey’s performance and people’s susceptibility to his commands–which, actually, seems pretty significant. The whole plan, and execution of it, is broad and generic and, with the limited six-issue space, comes across as rushed. I cannot say whether the tie-in issues expanded upon the depth of Godfrey’s impassioned pleas to Earth to recant its heroes, but in only six issues, the plot feels like it could certainly be explored more intriguingly. People end up suddenly convinced by Godfrey’s mental manipulations, burning heroes in effigy and parading around with signs demanding these heroes get the heck outta dodge.

Part of this may actually be caused by Len Wein’s love of repetition...and part of this may be caused by Len Wein's love of repetition. Each issue contains detailed retellings of important plot points, summarizing the events for anyone who may have forgotten or chose to jump aboard at a later issue. This is depicted most egregiously in the third issue, where the bottom fourth of each page is dedicated to summarizing the prior issues. Wein attempts to utilize this creatively, situating the summary as a dialogue between Darkseid and his welp of a servant Desaad, with the top portions of each page carrying the rest of the story along.

Intriguing an idea it may be conceptually, but in practice, Wein creates narrative whiplash. You’re constantly shifting between the actual events and the summation; such a trick is highly unnecessary and ends up hurting the entire issue’s pacing. I would have much rather seen Wein summarize the past two issues in a single page rather than dedicating a fourth of each page to the Darkseid/Desaad conversation.

All of this is meant to create a deeper point regarding our heroes: their importance to the DC Universe, shown not only in the good they’ve accomplished so far, but also in the good they could still achieve. Yet so much of this is done through discussion, talking heads, and summary, you feel as if the characters themselves become sidelined. Our heroes end up doing very little across the entire series, and moments of genuine heroism don’t seem significant enough to warrant an argument against Godfrey’s claims.

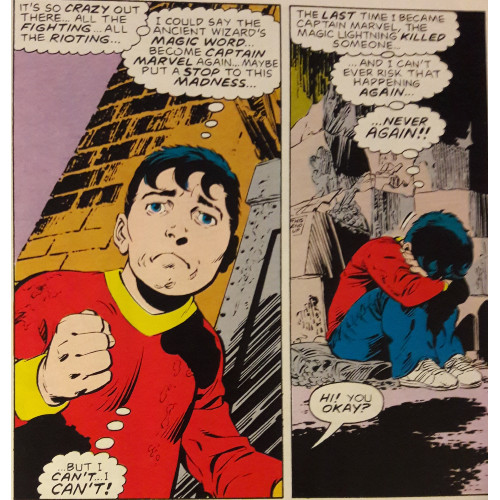

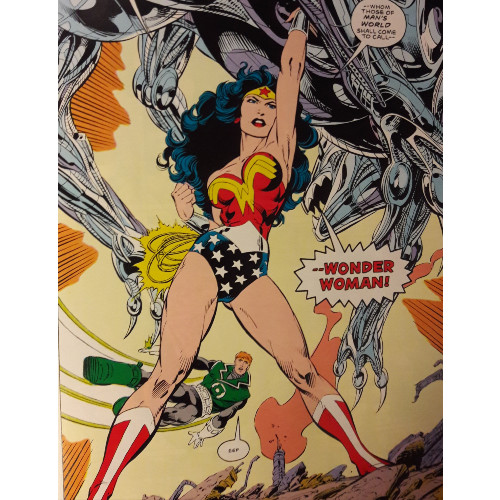

Wonder Woman pops up only at the very end to help fight some robotic dogs; Superman is stymied by President Ronald Reagan’s command to stand down (not the only time that’s happened to him, btw) and only becomes involved late in the game as well; Captain Marvel (back when DC could use the name) accidentally "murders" a supervillain, and Billy Batson spends most of the rest of the book certain he’ll never say "Shazam!" again; Green Lantern Guy Gardner behaves like an arrogant jerk, perhaps adding fuel to Godfrey’s fire.

"Legends" implies something beyond mortal, beyond mundane, beyond normal. It implies heroes worthy of ballads, stories, epics told and retold. None of the heroes, as presented here, feel as if they’re the stuff of legends already. And any hint that Wein and Ostrander intended for our characters to prove themselves as future heroes feels limited too–Wonder Woman, showing up for the first time in "man’s world" post-Crisis, does too little too late; Billy spends issues agonizing over his actions, with very little change until the plot absolutely demands it of him; even Doctor Fate pops up right at the last minute to lend a helping hand.

Each attempt at deeper characterization ends up misconstrued. I think Billy suffers the most throughout the series, as his initial arc is actually compelling. He’s a child with incredible powers tricked into thinking he’s murdered someone, causing him to curl up into a mental ball and not come out. That’s an engaging avenue to explore, and I wish Wein and Ostrander had the time and page count to probe more deeply. Likewise, Wonder Woman’s arrival on the scene is a dramatic moment, somewhat hurt but how suddenly it happens. I would have appreciated seeing Diana scope out the world she’s entered, observing it for what it is before determining to defend it. And Superman falls prey all too easily to the whims of an aging President, who himself suddenly retracts his decision in a single moment late in the game.

Funnily enough, the heroes who do the most in this series are the newly-introduced Suicide Squad, a ragtag gang of supervillains created for covert operations. Captain Boomerang, Deadshot, Bronze Tiger, Blockbuster, the Enchantress, and Rick Flag take out one of Darkseid’s minions, a villain even the Justice League couldn’t overcome. If your team of bad guys-turned-mercenaries prove themselves greater heroes than your actual superheroes, what does that say about the point you’re making about "legends"?

It’s sad because the premise, aside from its contrivances, sounds like it could make for a good book. Having a planet turn on your heroes and force them either underground or put them in a position where they’d need to prove themselves could make for compelling reading. One review I scoured called Legends a "morality play," with Darkseid and the Phantom Stranger specifically representing two sides of a philosophical coin. The threat of superhumans vs. the benefit of superhumans–which is greater? It’s not unlike Brad Bird’s The Incredibles, where heroes go underground after a series of disasters, reappearing years later to prove to the world it desperately needs protecting. Wein attempts to inject some of this late in the series, with the Stranger chiding Darkseid for engineering his own downfall–by attempting to eliminate heroes, he further entrenches humanity’s need for these costumed crusaders. Again, the point is interesting, yet muted by lack of exploration.

For anyone looking for any diamonds peeping up from the darkness, I hope you’re entertained by John Byrne’s art. Concurrently writing and penciling his Man of Steel limited series, Byrne churns out detailed pencils, about as good as he ever produced on Uncanny X-Men or Fantastic Four. His menacing Darkseid closely scrutinizes events, and his group shots of the old Justice League as well as the newly-formed team highlight each character fantastically. Byrne does as best he can with the script given him, but his presence feels like a way to pull in readers familiar with his art on better titles. Still, his work is a highlight of the title, if only because it offers familiarity to fans who recognize the artist’s legacy.

Legends does not possess nearly the scope of its predecessor nor the cultural impact. I never expected the multiversal-sized madness of Crisis on Infinite Earths, but I was hoping for a tale which neatly set the pace for a post-Crisis world. The book is packed with material, with the final issue hastily wrapping up a myriad of plot points while still introducing new concepts (oy). Yet that "material," deep as it hopes to be, merely bobbles along the surface of the reader’s conscience, never taking hold or convincing the reader of the deeper points regarding heroism it’s trying to make. If anything, Legends should be remembered for spearheading the creation of at least two new popular titles–John Ostrander’s original Suicide Squad run, and Keith Giffen and J.M. DeMatteis’ Justice League International. If you’re a fan of those series, read this as a prequel or perhaps an extended advertisement. From the Crisis, legends certainly rose…it’s just a shame you don’t see too many of them here.