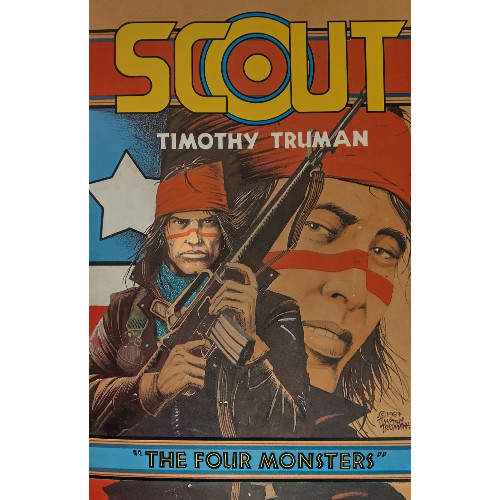

Random Reviews: Scout (vol. 1): The Four Monsters

These first issues of a complex dystopian series provide a startling look at an America not too dissimilar from our own

—by Nathan on October 4, 2025—

There are many, many reasons why I elect to read the particular comics I read. Sometimes it's because I'm fond of the central character and am encouraged to check out their continuing adventures. Other times it's because one story ends feeling unfinished, and I inevitably find myself seeking out the sequel to write "finis" on the narrative. And at moments it's because a particular creator captures my imagination and inevitably leads me to ask the question, "What else have they done?"

Such was the case with Scout, the Eclipse series written and illustrated by Timothy Truman.

Nearly two years ago, I read and reviewed Truman's Hawkworld limited series, a post-Crisis on Infinite Earths update on the origins of Katar Hol, the winged hero known as Hawkman. Some folks will note that Hawkworld actually added wrinkles to the character's already complicated history, but I chose to ignore those and approached the series for what it was: a taut narrative driven by moral quandaries and a torn hero, constructed upon well-illustrated worldbuilding focused on the societal and political divides within a grim dystopian society.

If you've read and appreciated Hawkworld, you'll find Scout to be somewhat of a similar animal.

Except it's our animal.

Based on Earth in the late 90s, Scout focuses on an America controlled by a corrupt president and government that keeps some of its citizenry placated and other members of society oppressed through targeted media and violence. Though published forty years ago (almost exactly–the series debuted September 1985) and though totally a work of fiction and imagination, Scout still delivers parallels between Truman's dystopian vision of America's future and our own society as we know it today.

Scout: The Four Monsters

Writer: Timohy Truman

Pencilers: Timothy Truman and Tom Yeates

Inkers: Timothy Truman and Tom Yeates

Colorists: Stev Oliff, Sam Parsons

Letterer: Tim Harkins

Issues: Scout #1-7

Volume Publication Date: January 1988

Issue Publication Dates: September 1985, November 1985, January 1986-May 1986

Publisher: Eclipse Comics

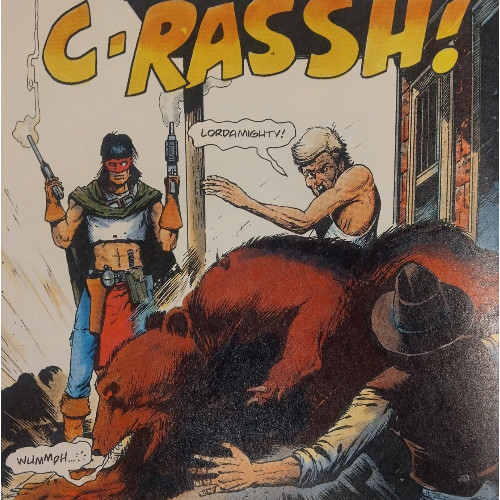

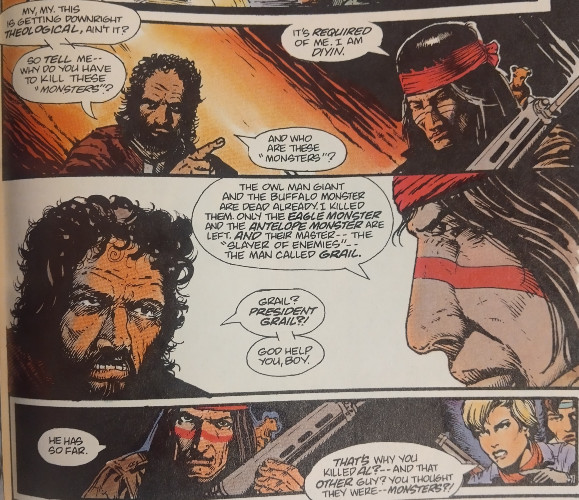

A Native American man, Emanuel Santanna, nicknamed "Scout," comes out of the wilderness with a mission–he has had dreams of four monsters, men disguised in human form as high-ranking members of society. He believes the current President of the United States to be one of those men and decides his mission will ultimately bring him into conflict with the Commander-in-Chief, who must die in order for our warrior to save America from the grip he and the other monsters impose upon the country.

That's Scout in a nutshell…though most folks are liable to toss away the shell and just call him a nut.

Tim Truman, much like he does in Hawkworld, provides a main character who is sick of the status quo, who feels that the powers-that-be have overstepped their bounds and demand fealty they have not earned from a country which will face their wrath if they do not bend the knee. In Scout, Truman develops a unique protagonist, one guided by his heritage, beliefs, and rituals, one influenced by his people's history. It's America's darkest hour, and a member of the First Nations takes it upon himself to take back a semblance of balance and sanity that were originally taken from his people a long time ago. Truman seems to find the idea appropriate and worth exploring.

I understand, to an extent, stereotypical representations of Native American people in media, and I am not aware if readers have found Scout to be offensive or better aligned with how characters of his ethnicity and background should be treated. I myself can't pass too detailed a conclusion, but Scout does not come across as cliche. He possesses traits seen in other Native American characters–a great attunement with the environment, a connection with spirits–but these are not presented as derogatory or demeaning to the character. There's a hint of poetic justice to his actions, perhaps a bit if irony, as the man who must rescue all of America comes from a people who should never have been oppressed at the start.

I make that distinction to pivot and discuss an important bit of conflict throughout the volume: whether Scout dreams are legitimate. Truman is pretty surreptitious with the concept, which I think works from a certain angle. Were he to treat this as too clean-cut, the sudden arrival of powerful spirits as key figures in American politics and culture would seem somewhat outlandish and add a strange layer of magic and non-realism to the narrative. Introduced as possible figments of Scout's imagination, however, these monsters now weave in a mental aspect. As we learn more about Scout as a character and as we grow to trust him, we enter a place of doubt and wondering ourselves…could it be, could it really be, that Scout sees the truth? He's followed around by a chittering chipmunk that claims to be his guide, and though nobody else addresses the chipmunk directly, the little guy certainly seems real enough…right? Truman derives tension from the reader's wavering faith in Scout and his dreams, extending this to characters who doubt how much they can trust the man, despite his skills.

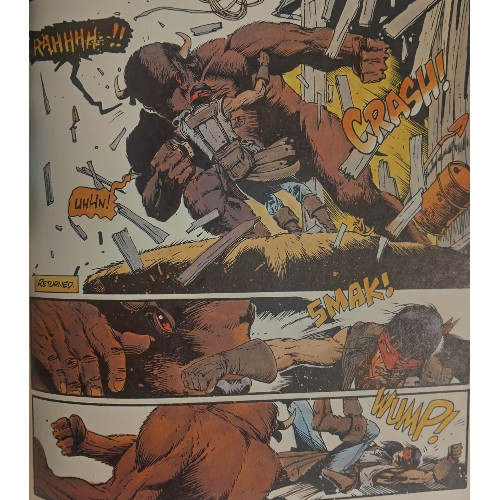

Even if we trust Scout, even if we believe he's in the right, Truman also allows us to grapple with the consequences of Scout's actions. Our friend is a driven man, yet the ripple effects of his violence draw other characters into harm's way and even impacts society at large. The government wants to see him as deranged and dangerous–and just maybe, it wriggles in the back of our brain, he is–and that the fallout of whatever Scout is doing will be worse than the positive effects. It's a fairly strong argument, particularly when Scout destroys the country's oil reserves. He may be our hero, but if these extreme, violent actions are his methods of heroism, how much do the results matter?

What is never in question is Truman's villains–even if they aren't physical monsters, they're fairly horrible individuals who are responsible, in part, for America's current condition. A president who keeps his vice president addicted to drugs, a filmmaker known for being cruel and abusive, an agricultural minister who hangs farmers…they each have contributed to society's inability to pull itself from the wreckage of wars and poverty. We learn to despise them fairly quickly, and it's their evil which makes Scout's actions look somewhat more heroic. Yeah, he's crippled America's oil industry, but if it's to keep the villains from stockpiling it for their own needs, that's good…isn't it? That's the wrestling you have to contend with as you read, and this juxtaposition of Scout's anti-hero qualities against the scrupulousness of his enemies makes the interplay engaging.

A foil for Scout, a former friend named Ray from Scout's military days, is given his own arc, his obsession with serving his country and catching Scout creating a descent into madness meant to parallel Scout's own mindset. The final issue allows some explanation for the division between Scout and a few other characters, nicely providing alternate perspectives to our main hero's and highlighting the tragedy of fallen friendships. The narrative declares Ray's situation tragic, his passion misguided or misaligned–like Scout, his beliefs drive him in a certain direction, yet unlike Scout, we're not meant to see Ray as anything other than unstable. Where you can quibble with Scout's motivations and actions, you are not allowed that opportunity with Ray. He's a villain, an unfortunate villain, and the person for whom Scout's actions are the most personal.

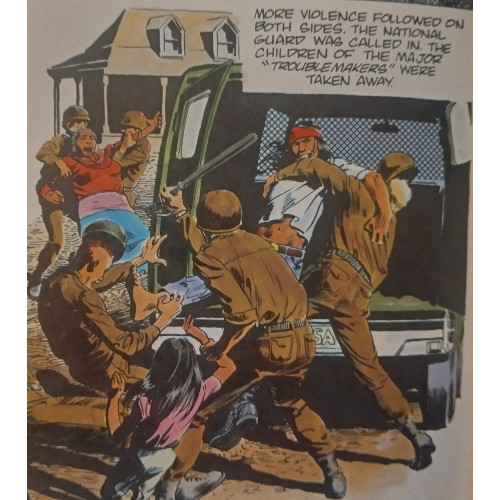

Even with the spiritual sheen covering the book, Truman has grounded Scout in a fairly reasonable, grim outlook of the future, and there are moments throughout which make me react strongly towards the arc's continued relevancy, even if some elements feed a tad dated. A televised broadcast set to bolster the President's vision of a "New America" is flanked by an advertisement for military-inspired kids' cereal and a commercial about reporting communist neighbors; food and race wars are indicated to be part of America's collapse as a country during the 90s; we're told Mexican soldiers were welcomed across the border to hunt "refugees." Little bits such as these, small twists on reality, help Scout's impact as commentary on the then-present political landscape and even now. Divisions between neighbors and races, manipulative media, political subterfuge, and even harsh critiques of political offices all feel very part-and-parcel of our present day, even if we'd wish it weren't true.

The reality of this is bolstered by Truman's art, who applies a very realistic brush to the world. Setting his story in what was, at the time, the future of the 1990s, Truman delivers a possible look at how dystopian, fallen America could look and function. His world is not overrun by futuristic technology, incorporating just enough advancements to make sense and aid his message. That abusive filmmaker lives in a giant mansion with an anti-gravity swimming pool–it's just a floating cube of water, yet it looks futuristic enough to be cool and also make the filmmaker look even more like a jerk for owning such an advanced form of relaxation. Yet most of the world Truman carves is as we see it or are twists of how we see it–the homeless of Houston camp out on rooftops, the President has exchanged the White House for the Astrodome, and television carries the possible potential to poison. The world doesn't need to be controlled by robots or fall into nuclear holocaust for life to be upended.

If you're willing to let Scout lead you, you may be taken to unexpected places. You may be asked to grapple with whether ancient spirits have taken physical form and pose a threat to America. You may wonder whether Scout's vigilante tactics are what the country needs to experience to be pulled from the influence of corrupt leaders. The lines you see on a map which carve our country into states and counties and towns are blurred, and so are the philosophical lines which divide right from wrong, hope from hopelessness. Scout won't necessarily provide you the straightest path to walk those lines, as some of his intentions and actions are somewhat questionable, but hopefully he'll provide enough of a focus for the reader to decide just how fuzzy those blurry lines are.