(Strand)om Stories: X-Men: Children of the Atom Review

This limited series reframes the original X-Men's formation, offering depth and characterization lacking in the inaugural Stan Lee/Jack Kirby issues

—by Nathan on August 24, 2023—

A while back, after perusing a chunk of Chris Claremont’s storied run on Marvel’s persecuted yet plucky mutants, I dove into the early Stan Lee/Jack Kirby narratives. I criticized those opening issues harshly, holding high the hilarity of the original concept and deriding some of the storytelling. Five teenagers–Cyclops, Marvel Girl, Angel, Iceman, and Beast–are brought together under the auspicious of a bald, wheelchair-bound telepath to wage war against villainous mutants hell-bent on enslaving a world distrustful of mutants at best, downright hateful and bloodthirsty at worst.

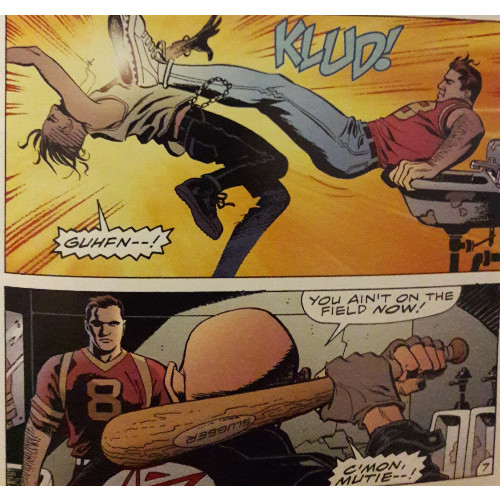

The series, particularly in those opening issues, takes its premise at face value and trusts the reader to believe that nearly every human being any mutant character could run into would automatically hate them on the spot. I bumbled through those issues, somewhat frustrated with the premise’s universality of mutant-centric hatred; Lee and Kirby, doubtlessly limited by the confines of the Comics Code, couldn’t outright claim these mobs would band together and burn our mutants at the stake or murder them in cold blood, but the hatred, though simplified, is overwhelming. I understood Lee and Kirby’s muddled attempts at incorporating themes of racism and human value and equality; the series’ structure and core tenants, unfortunately, left the field fallow. Other writers have better encapsulated the "mutants as race relations" metaphor.

Take Joe Casey, for example, and this early 2000s series which gives us a more definitive look into how Marvel’s merry mutants united like strands of genetically modified DNA.

X-Men: Children of the Atom

Writer: Joe Casey

Pencilers: Steve Rude, Paul Smith, Esad Ribic, Michael Ryan

Inkers: Andrew Pepoy, Paul Smith

Colorist: Paul Mounts

Letterers: Jim Novak, Richard Starkings, and Comicraft’s Wes Abbot

Issues Collected: X-Men: Children of the Atom #1-6

Volume Publication Date: November 2001

Issue Publication Dates: November-December 1999, June-September 2000

While reading Children of the Atom (which, coincidentally, bears the same name as the X-Men’s first Epic Collection), I experienced an epiphany: what Lee and Kirby’s issues lacked was a “Why?” In those original issues, mutants are hated because they are mutants. Okay…that’s fine, I suppose. Perhaps here and there exists a line of dialogue about humanity often failing to embrace the differences between people, but aside from that, Lee and Kirby expect you to believe that most people in the Marvel Universe just hate mutants to hate mutants. Hatred is a reflex, some automatic process that almost can’t be controlled, like when your doctor taps your knee with that little rubber hammer...except picture you kicking hard enough to put your doctor through the wall because, clearly, he intended to harm you with the little rubber hammer.

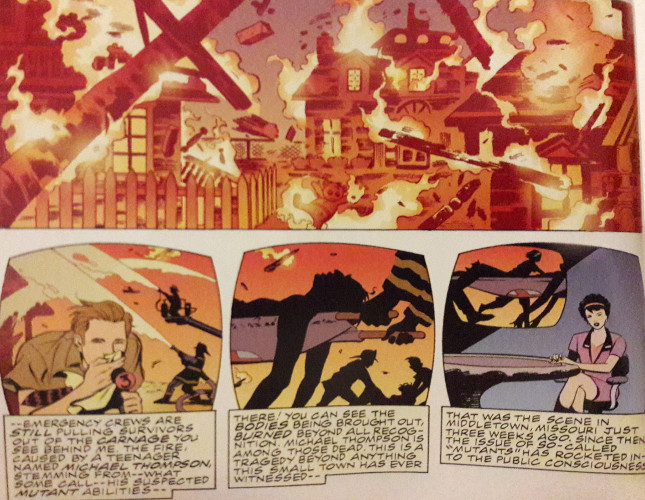

In Children of the Atom, Casey justifies the public’s hatred and fear of mutants from the start, showcasing a neighborhood lit ablaze by the burgeoning abilities of a mutant teenager. Hank McCoy later appears to push a trigger-happy adolescent from the top of a building (an accident twisted by the media). News and talk shows describe anti-mutant hysteria, adding gasoline to a fire already raging. In certain instances, these mutant teenagers actually pose a viable threat, giving some credence to the sentiment against them. Casey never sides with the dissenters, but he offers a compelling argument for why people are afraid. If not properly controlled, or if used for devious devices, mutants have the potential to hurt…or kill.

To that end, Casey adequately hypes the hysteria–it’s a necessary plot point, pushed as an agenda by a rising leader in an anti-mutant militia. Through broadcasts and interviews, Casey apes Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns by giving humanity a voice. We’re not just peppered with the idea of a faceless mass of unnamed people rising against mutantkind for “reasons.” We're not just incentivized or incensed by propaganda peddled by a ponderous professor. We’re given side characters and stories–a young man featured prominently (perhaps the most prominent character outside the original five X-Men and their plain-headed professor) finds himself hunted by former friends when his mutant abilities manifest. Scott Summers, Hank McCoy, Bobby Drake, Jean Grey, and Warren Worthington III all go through transformations–physical as well as emotional–as they come to grips with their abilities and how best to utilize them.

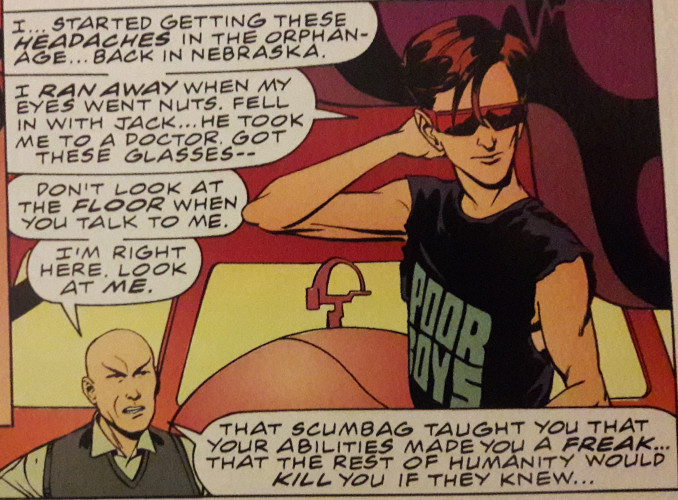

Casey must play with each central character, as well as supporting cast members including the anti-mutant militia leader, Charles Xavier, Magneto, and FBI Agent Frederick Duncan, who appeared as early as Lee and Kirby’s X-Men #2 as a liaison between Xavier and the government. This means not every character is allowed the same depth or detailed origin story–we aren’t given as much detail, for example, on Beast, Iceman, or even Cyclops’ origins as Gary Friedrich offered in backup strips during Roy Thomas’ first X-Men run. We are, however, given tastes of each character which engagingly set up where they’re at and how they react to their abilities.

Each character responds differently, governing the series’ internal conflict even as external conflict comes from racist skinheads and bullies. Our X-Men don’t gather, formally, until late in the series, and Casey throws in a handful of interactions between various characters beforehand–Scott, Hank, and Bobby all attend the same school, Bobby and his parents are present when Hank grapples with the gun-toting teen, and Scott and Hank have a brief interaction in the school lunchroom. Otherwise, Casey navigates changes individually. Jean is given a brief arc as her powers go wild unconsciously (perhaps foreshadowing some of the power she’d later exude as Phoenix and Dark Phoenix?); Warren, recklessly, dons a mask and costume, seeking to fight crime before the militia learns his secret identity; Bobby’s powers first manifest themselves as uncontrollable cold before escalating into uncontrollable ice-formation.

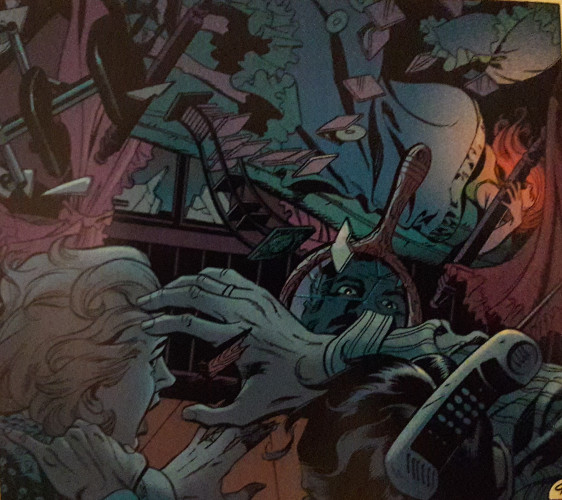

Though Casey, then, justifies the public’s fears of “mutanity,” he also hones in on how our protagonists grapple with their abilities. Again, it isn’t just that they’re mutants, different from the rest of the world. Their powers come with consequences. Warren imperils himself after reveling too much in his abilities, his cockiness apparent at several points. Jean sees the damage her powers cause when she lacks control. Bobby runs away from home. Scott is taken in by a career criminal and forced to use his powers to help rob a nuclear power plant. How these changes impact the lives of otherwise normal teenagers is given scope–personally, relationally, physically, and societally. It’s Lee and Kirby’s original concept given deeper life and meaning. Some of these concepts–such as Angel’s early foray into masked vigilantism and Scott’s unwilling participation in a robbery–come straight from the aforementioned backup strips (the latter written by Friedrich, the former by Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel). Other elements are added or manipulated, such as Jean’s burgeoning abilities (Marvel Girl never received an origin series of backup strips in the original issues) or the boys’ interactions at school.

Children of the Atom, in this vein of thought, is then notable for what it chooses to alter from the original narratives as much as what it chooses to keep. Cyclops’ interacts with his “foster father” (applying the term as loosely as possible) Jack Winters take a somewhat harder edge in this series; Casey, perhaps rightfully so, skips a subplot introduced by Friedrich where Winters is transformed into the Living Diamond, an interesting development in the original strips but a potentially distracting subplot here. Warren is attacked by a Sentinel far before they were introduced in Lee and Kirby’s run, invoking the somewhat terrifying idea that the Sentinels were in development far before readers realized from the original issues. Casey, interestingly, also keeps Magneto’s involvement to a minimum–he’s not the real villain, finding himself at odds with the anti-mutant militia as much as the X-Men are. Casey allows Magneto some of the moral complexity Claremont gave him, using the Master of Magentism in an almost anti-hero role as opposed to a world-dominating villain.

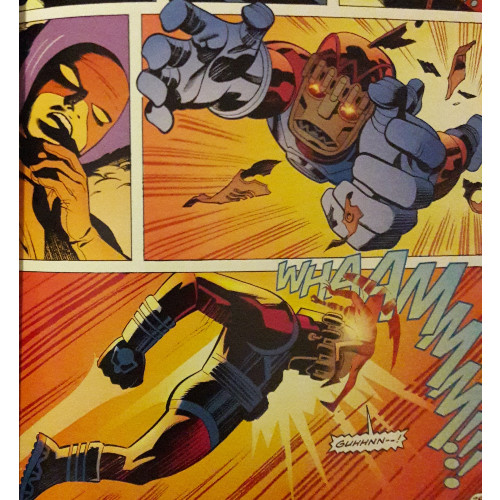

Artistically, it’s difficult to say the pencilers used here feel distinct, but I wonder if that’s due to Paul Mounts’ consistent color palette. Steve Rude illustrates half the book, with Paul Smith (who has previous experience illustrating X-Men stories) and Michael Ryan replacing him for the fourth issue and Esad Ribic replacing them for the final two installments. Rude, Smith, and Ryan’s work feels indistinguishable from each other (which, admittedly, helps the series maintain its consistently Kirby-esque character designs and style), and though Ribic’s art feels more distinct, it’s a far cry from his work on Robert Rodi’s Loki series or Jason Aaron’s “Gorr the God-Butcher” saga. If anything, the art similarities keep the issues consistent; you’re never jolted when transitioning from one issue to another.

Think of this series as an alternative to the original Lee/Kirby run (and, to a lesser extent, Roy Thomas’ run), even if these issues occur before the events of those tales. This feels like a far truer origin story for the X-Men than we’ve received previously–a highly engaging dive into how these misfits were unified. We’re given decent backstory for our protagonists and proper motivation for our antagonists, highlighting the complexity in mutant/human relations I wish had existed from the team’s inception in 1963.