Distinguished Critique: Aquaman: The Legend of Aquaman Review

Aquaman's post-Crisis origin isn't exactly a classic, even if it tries to modernize the King of Atlantis with a splash of darker ambiguity

—by Nathan on January 15, 2024—

Y'all remember that one line in the first Justice League trailer, where Daredev–I'm sorry, Batman tells Aquaman: "I hear you can talk to fish"? Remember that? It was funny, right? The humor (or, if we're being cynical, "humor") hinges on completely devaluing DC's king of Atlantis, transforming a guy with control over 71% of the Earth's surface and a legion of aquatic creatures into a dude who just chats with your pet goldfish as it lazily swims around its bowl.

I don't consider myself an Aquaman fan, so if I critique the film's dialogue, it's primarily because the whole "Aquaman talks to fish" bit has been done to death, not necessarily because I carry a "Respect Aquaman" sign around with me in protest. At his core, yeah, the guy should be used as a powerhouse all the time, given his remarkable abilities. But there's something about a dude in orange chainmail and green pants riding in on a seahorse to save the day which just feels...funny.

Maybe even a little fishy.

I am not well-versed in Aquaman's many iterations, but as I've been rummaging through the DC Universe's post-Crisis on Infinite Earths landscape and studying these updated origins or versions of characters, I keep probing deeper. It's interesting to watch how Green Arrow went from a Robin Hood ripoff with gimmicky arrows to a Robin Hood ripoff who hurt people, or how Green Lantern became an alcoholic, or how Batman became…darker Batman. In continuing my quest, I elected to peer beneath the waves to the deepest reaches of the ocean, seeing how the tidal wave of change swept up DC's version of the Submariner.

Aquaman: The Legend of Aquaman

Writers: Keith Giffen (plot), Robert Loren Fleming (script)

Pencilers: Curt Swan, Keith Giffen

Inkers: Eric Shanower, Al Vey

Colorist: Tom McCraw

Letterers: John Costanza, Agustin Maus

Issues: Aquaman Special #1, Aquaman #1-5

Publication Dates: May-December 1989

The immediate post-Crisis world is weird.

Through reading these narratives, I’ve been trying to figure out what exactly was different once the dust settled and what remained the same. Batman and Superman get completely different origins that planted their roots in a more modern era, but Green Arrow, though given a facelift by Mike Grell, recalls his sidekick Speedy's drug addiction, which happened during the pre-Crisis Dennis O'Neil/Neal Adams run. I don't fully grasp what was made non-canonical from pre-Crisis and what was allowed to remain intact.

From what I can gather, our fish-fluent friend was given an update in the wake of Crisis, temporarily switching out the orange-and-green suit for a blue outfit, and a four-issue limited series, which has not been collected, before receiving the Special issue and five-issue series collected here. And in doing my darndest to research how all this fits together, the best I can understand it is this: for the time, the Special (from where this volume gets its "Legend of Aquaman" title) was the then-chronological post-Crisis origin for the hero, later updated and given additional details which are not represented here. The five-issue series appears to be a continuation of the Special, which ended with Aquaman abandoning Atlantis, his wife Mera, and his people following the death of his son at Black Manta's hands. So the Special updates Aquaman's origins and tethers them to pre-Crisis narratives which were still canon (such as the death of his son), and the five-issue series included in this volume builds off the ending of that Special.

This could be wrong, I'll be honest. My research indicates this all makes sense, but I am allowing for errors on my part. But much like my Hawkworld review, where I set aside Hawkman's complicated history in favor of focusing on the current story, I want to divorce myself slightly from Aquaman's context to analyze the narratives contained in this volume. Understanding the larger picture in which this piece fits is certainly important, but from what I can tell, DC creators kinda just did whatever they wanted with Aquaman…nothing seemed to stick. And the character's origin was revitalized later by Peter David, so I'm not even sure how much of this is canon anymore.

One immediate element to note this is a darker take on the Aquaman mythos than what, I assume, was presented previously (the murder of his infant child notwithstanding). This appears to have been a running theme through many of DC' post-Crisis updates. Green Arrow hurts people with pointy projectiles. Hawkman serves a fascist planet. Green Lantern's an alcoholic. Even Batman feels more grounded and grittier than prior versions, including the Dennis O'Neil/Neal Adams era. Heck, Mike Baron and William Messner-Loeb's early Flash issues had Wally encounter some grim situations for a surprisingly spritely character. And Aquaman…well, Aquaman becomes a terrorist. Kinda. Let's split the difference and call him a "revolutionary."

The five-issue Aquaman series sees Arthur Curry return to Atlantis after a period of wandering, only to find his beloved city has been overrun by invaders, with a standing army having conquered the realm. Aquaman joins a group of revolutionaries to rescue his people. It's a unique idea by Giffen, Fleming, and Swan, having the character become this legendary leader, rescuing his people from enslavement. Suddenly, Aquaman isn't just a popular hero saving the world from starfish-faced conquerors; he's some kind of Ben-Hur or Spartacus character, brought in to free an ancient people.

You'd think the idea would work better than it does; on the surface (pun not intended), the concept is solid: much like fellow comic kings Black Panther, Prince Namor, or even Doctor Doom (and, heck, just for a bit of barefaced self-promotion, let's throw in King Arthur from Mike Barr and Brian Bolland's Camelot 3000 series), Aquaman is a man governed by the needs of his people and should very well wrestle with a sense of guilt and perhaps even some renewed vigilance when those people are mistreated by outside forces. And he's certainly nationalistic and protective but nothing beyond dogged determination that feels overwrought and emotive. There's a lot of passion expressed here, but we get little insight into Arthur's character beyond his defensive attitude. The difference between this series and, say, Christopher Priest's representation of Black Panther is that Priest's T'Challa is a man willing to go to any lengths, genuinely wrestling with the morals of protecting his people and the lines he's willing to cross. Aquaman comes with a few moral qualms–he attempts to stop a particularly cruel act of terrorism–but these issues float through like a bit of refuse swept along by the narrative's stronger current. The wrestling, the internal struggle, gets lost in the undertow.

Giffen and Fleming are trying to work with the pieces they have, stringing along some subplots to engage the reader, whether that's the identity of the mysterious invaders or the fractured relationship between Aquaman and his wife Mera. These are handled well enough, flitting through the pages and serving the larger story rather than diverting attention. We're not given anything remarkable or memorable–some trite statements are made of Mera's mental well-being following the death of her son, twisting her into a vengeful, violent woman deserving of better handling. The crux of the conflict between Mera and her husband makes for interesting reading and a decent approximation of how both characters handle the loss of their child; building to their confrontation, however, is messy, and like other sentiments expressed in the book, somewhat stale.

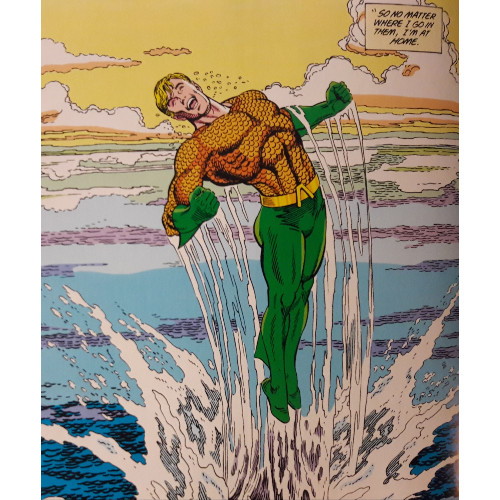

Taking a step back, briefly, Giffen, Fleming, and Swan provide Aquaman's post-Crisis origin in the Special issue, and fans of the first Jason Momoa-led movie may recognize some elements taken directly from the opening pages. The assembled creators explore some unique ideas, particularly how Aquaman's humanity intersects with his Atlantean heritage. Much like fellow Justice Leaguer Superman, Aquaman represents the overlap of two worlds, and Giffen and Fleming nudge at this idea of Aquaman not being fully comfortable in either living fully beneath or above the sea. He can't stay in either place forever, living in this limbo between an Earth which doesn't understand him (a concept more thoroughly explored in Mark Waid's Justice League: Year One) and an Atlantis where the responsibility of rule feels confining, despite whatever love Aquaman has for his people.

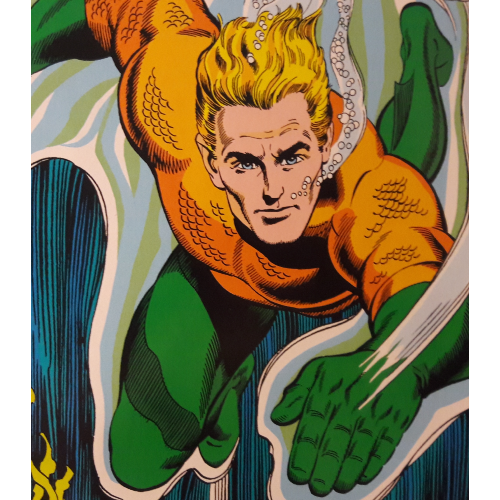

That Giffen, Fleming, and Swan guide all six issues means the art and writing always feel consistent. I largely enjoyed Swan's work on "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?" and similar character designs–accentuated by detailed cheek bones, emotive eyes, and fluid action (quite literally as most of this narrative happens underwater)--create solid, recognizable characters here. Colorist Tom McCraw allows for Atlantis to pop from the page, setting it against consistent blue backgrounds, and the same is true of our characters–make fun of Aquaman's color scheme all you want, but it draws the eye in every panel. Greens, pinks, and metallic grays stand out from the surrounding seas as well, keeping the world our orange-outfitted monarch traverses consistently attention grabbing and light, despite some of the heavier subject matter.

I can't say this volume made me an Aquaman fan. There are interesting concepts strewn throughout, somewhat waylaid by a generic story with little deeper insight into the character or his motivations. You can't say this redefined the post-Crisis Aquaman the same way John Byrne reshaped Superman, Frank Miller updated Batman, or Mike Grell changed Green Arrow. I do hope to check out Peter David's Time and Tide series somewhere down the line; maybe this will offer a stronger tug in making the character…current.