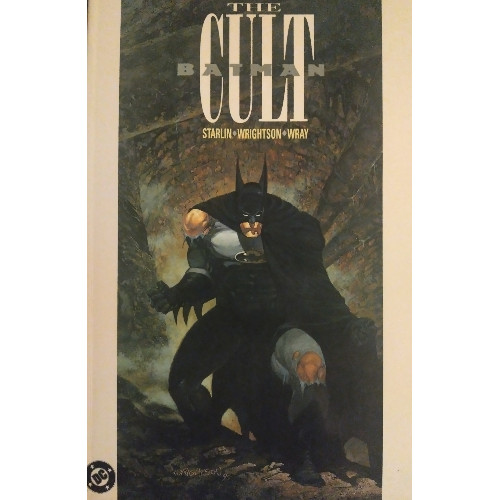

Distinguished Critique: Batman: The Cult Review

A grim portrayal of psychological manipulation feels relatable today, creating a dark scenario a broken bat must break free from

—by Nathan on August 29, 2025—

"Open your eyes and see the unknown

My visions have turned divine

A taste of false eternity

The venom intertwines

Drink in the promise

Let it flood your veins

The fire will wash it away

Bow to the god who's rotting inside

In worship, we will welcome the night"

So screams Ryan Kirby, lead frontman for Christian heavy metal outfit Fit for a King, in the opening lines of "Witness the End," the final song on their latest album, Lonely God. The entire album is a cry against manipulation, particularly from religious leaders who twist truth and make false promises to draw in believers-turned-victims. The band takes shots at technology, media, religion, various strands which demand our attention and can ultimately victimize the vulnerable if we're not careful. There's a difference between actual truth and what is touted as truth, but that line is thinner than we'd like to imagine and can easily be twisted by folks with dark-hearted intentions.

Purely coincidentally, during the first few days I spent listening to Lonely God, I also read a fairly appropriate comic: Jim Starlin and Bernie Wrightson's limited series Batman: The Cult. Much like the new album, Starlin and Wrightson's series is a denunciation of religious manipulation, the ability of one man to take and twist belief to his own dark ends. As I just reviewed Starlin's other treatise denouncing religious fanaticism in Marvel's Infinity Crusade, I thought it the right time to review this narrative as well. There is power in words, power in belief, and like the Goddess attempted to twist the Marvel Universe into her perfect vision, so does Deacon Joseph Blackfriar intend to use that power to mold Gotham City in his image.

Fortunately for Gotham, a staunch defender stands in the deacon's way.

Or he will once he claws his way out of the sewer he's been trapped in the last week.

Batman: The Cult

Writer: Jim Starlin

Penciler: Bernie Wrightson

Inker: Bernie Wrightson

Colorist: Bill Wray

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: Batman: The Cult #1-4

Publication Dates: August 1988-November 1988

Before "No Man's Land" made Gotham City a war zone, Deacon Blackfriar broke Gotham…and before Bane shattered the Dark Knight Detective over his knee, Deacon Blackfriar broke the Bat.

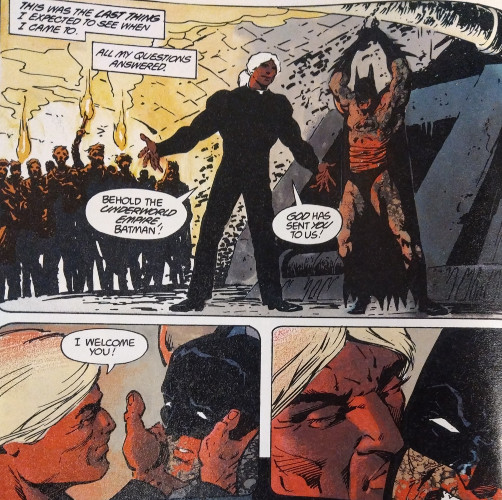

Starlin and Wrightson promise a different kind of Batman story from the very beginning of the series, as we witness the Caped Crusader in a state of anguish–defeated, drugged, and dangling from a sewer pipe. We don't know how he got to such a state, but we do know the unthinkable has occurred: Batman has been beaten, and he is slowly being broken, his logic and sense of reason whittled away. Dreams, along with stories of the deacon's past, physical violence, and the possible use of drugs chip at Batman's sense of self, transforming him into a willing servant, or as far as one can be willing when they can't realize their personality has been artificially replaced by the demands of another human being.

This is a Batman horror comic, but not in the way you may think of a horror comic. Outside grisly dream sequences and drug-induced hallucinations, we don't see Batman fight actual demons or reanimated corpses; we aren't jumpscared by spooks hiding around corners. The horror does come from the visuals at times, absolutely: grim violence is meted against cops and criminals, blood splashes the panels, a sewer tunnel is lined with corpses, and someone bathes in a pool of blood while bodies dangle from above. Swamp Thing co-creator Bernie Wrightson is allowed his hand at the grim and gruesome, mingled with the brutal groundedness of Gotham City. Were it a horned demon bathing in blood, our senses may not feel so disturbed. But it is a man taking the plunge, a seemingly regular fellow, and you have to ask yourself what kind of individual would willingly commit such an action. That's where the real visual horror lies, in the mundane taken and twisted to a nearly unfathomable degree.

The internal horrors, however, are where our focus should lie. We are treated to the terrifying psychological breakdown of a man, aping the psychological breakdown of Gotham City as the deacon sinks his claws into the infamous town. It's not enough for the audience to know Batman is the hero and the deacon is the manipulative mastermind–our hero has to believe it himself, yet subject as he is to the deacon's masterful mind-bending, we wonder how long it will take for him to reach that same conclusion. His reality has been replaced with the deacon's, and all manner of reasons, excuses, threats, and people are against Batman ridding the fog from his brain.

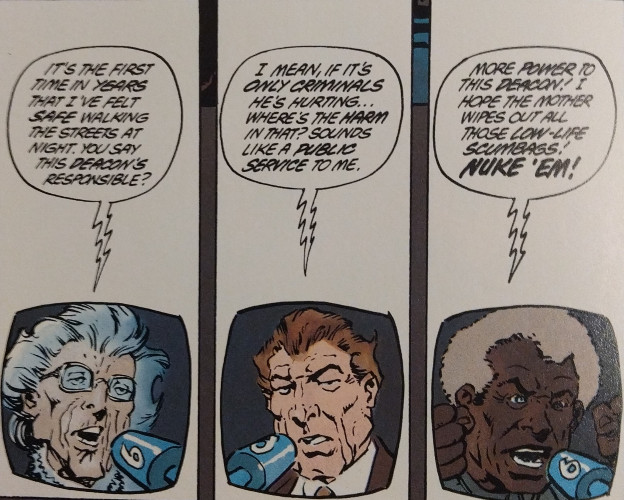

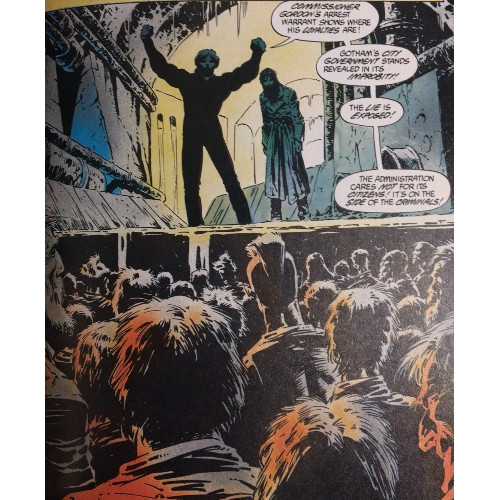

Like with the physical horror, Starlin draws Batman's ordeal from reality, from the idea that real people in our world have succumbed to the seductive draw of religious leaders for power, love, belonging. We're told of at least one man who's joined the deacon's ranks willingly, which is scary for reasons different from mental manipulation. As the narrative progresses, others join to the degree the news begins reporting on it, and the sight of people crossing into Gotham to find purpose and escape the feeling of being disenfranchised is powerful and still feels like a relevant visual nearly forty years later. Manipulation such as this reaches out to those who feel they have no other avenues to take, extends empathy and purpose while hiding a lust for power and control beneath.

Starlin finds this cunning balance between presenting Blackfriar as a devious criminal mastermind and a self-styled savior, adding complexity to the narrative. As Gotham begins to decay, and as martial law takes charge to quell the increasing violence against not just criminals but members of local government and law enforcement, Blackfriar offers a measure of control to stabilize the situation. Again, you, the reader, know the deviousness behind his machinations, but for the sake of the story, it's difficult to argue he doesn't play the pieces well enough to fortify a victory for himself, regardless of the lies he tells the GCPD, as well as his own followers, to achieve that victory. Noble intentions mask the sinister motivations beneath his skin, and you can begin to see the personality which so easily draws people to his side.

You probably wouldn't agree with Blackfriar's motivations and methods–and if you do, that's a different conversation we need to have–but it doesn't matter much whether you do. As long as the reader sees the techniques Blackfriar uses and believes that he would appeal to some people as an orator and leader, Starlin has done his job. The problems Blackfriar supposedly addresses–disenfranchisement, poverty, a limp fish of a local government–are still relatable these days. We trawl through a swamp of religious corruption, but within that mire, Blackfriar leads Batman through snake-infested waters of genuine issues. Starlin doesn't seek to solve homelessness, purposelessness, or failed bureaucracy in this narrative, but he does enough to make us take notice. Yes, those problems exist, and we should resolve them, but we don't need a silver-tongued preacher to offer his own solution disguised with frivolous religiosity.

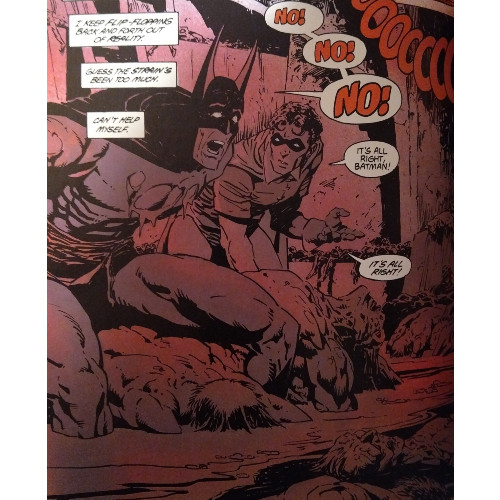

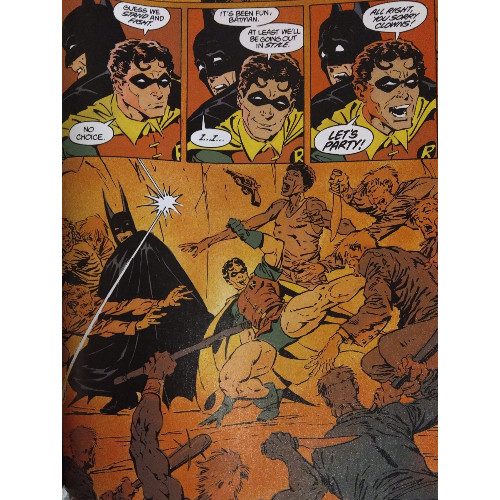

Batman, largely presented as a victim, still remains our central protagonist, but the argument could be made that Robin is the clear hero of the series. Our Robin is Jason Todd, this series published shortly before his death, I don't mind Starlin's use of Jason in other stories, such as in early post-Crisis issues of Batman; the young man has a sense of purpose about him which drives him forward, even if his lack of decorum, his harsh wit, and his violent tendencies didn't endear him to fans. This is probably the best representation of the character, as Starlin has Robin shoulder the responsibility of rescuing Batman from the pit and returning him to civilization. It's Robin who must lead him out, Robin who must fight and confuse their pursuers, Robin who must encourage Bruce to stand and fight for himself when he feels all his strength has left him. The scenes with Robin shine–not so visually, as they mostly happen in a sewer–allowing his character to come forth and putting that snark, that drive, that tendency towards violence be put to very good use.

The Cult owes a debt to Frank Miller, as do other Batman narratives of the 80s, particularly in its art. Wrightson illustrates the death of Bruce's parents in a similar style to Miller's work in The Dark Knight Returns, and he and Starlin employ the "talking heads" reporter and "man on the street" interview segments Miller utilized in that narrative as well. These don't make The Cult feel derivative; these pieces feel like a proper homage to the work of another creator, particularly because Starlin and Wrightson don't over-rely on references to carry their narrative and instead use them at integral moments. When Bruce recalls the night his parents died, Starlin and Wrightson appear to be saying "This is how it happened, canonically. This is how the Bruce Wayne of today will remember that night, the same as how the Bruce Wayne of the future will remember it however many years from now." The Batman of The Cult and the Batman of Returns are the same Dark Knight, the same driven hero, the same psychologically complex character.

If you have not read The Cult, I'd suggest you remedy that. I won't tell you to do it, nor will I brainwash you with drugs to force you to do it, but I'd argue this belongs on your bookshelf with other Batman stories from this era. The theming is strong, a dark, grounded concept written well into this tale of a broken vigilante and the steps he and others must take to be liberated and rescue Gotham from a threat that isn't an evil clown or a man obsessed with penguins. Deacon Blackfriar is the kind of villain you'll find in the news or in Netflix documentaries. Cults are real, and the influence behind them is mapped well here, creating a horror story that wouldn't even need all the blood and violence to cause terror. Wrightson adds the blood and gore where needed, but he and Starlin know the greatest trick they have is in the psychological fear and brokenness which results from someone digging into your mind and replacing who you are with who they demand you to be.