Random Reviews: Swamp Thing: Dark Genesis

Despite a mediocre final third, this volume successfully introduces a monster who wishes to be a man, pitting him against men who behave like monsters

—by Nathan on June 7, 2025—

When I reviewed the first volume of Alan Moore's run on Swamp Thing, I briefly commented on Len Wein's contributions, noting how ol' Swampy was another character co-created by Wein (alongside Wolverine and the mid-70s incarnation of the X-Men) who went to greater heights under other writers (Wolverine under Chris Claremont and Barry Windsor Smith, specifically, and the other X-Men under Claremont). I referred to it in a "shrug your shoulders, well, gosh, that sucks" kinda way and moved on.

Today, I intend to give Mr. Wein his due by expounding on some of the original Swamp Thing narratives he developed in the 70s. The roots for Moore's take on the character are found here, in the dredges of murky swamp waters. A story wrapped in betrayal and scientific astonishment give birth to a seemingly mindless muck monster, as Wein and horror icon Bernie Wrightson unleash Alec Holland's horrific alter ego onto the world…with fascinating results.

Swamp Thing: Dark Genesis

Writer: Len Wein

Penciler: Bernie Wrightson

Inker: Bernie Wrightson

Colorist: Tatjana Wood

Letterers: Gaspar Saladino, Ben Oda

Issues: House of Secrets #92, Swamp Thing #1-10

Volume Publication Date: December 1991

Issue Publication Dates: July 1971, November 1972, January 1973, March 1973, May 1973, August 1973, October 1973, December 1973, February 1974, April 1974, June 1974

Publisher: DC Comics (original issues), Vertigo (DC Comics imprint–collected edition)

This volume pulls together a series of narratives introduced in the 70s yet not exactly created for the standard superhero fan, setting the stage, I'd argue, for the even darker material Moore would dabble in during the 80s. Kids with grubby fingers in the 70s certainly pulled this title off the shelves, but inside, they'd find captions and images akin to scary movies you don't watch at night with the curtains open. Spider-Man fighting the Green Goblin again this ain't, the Goblin's grotesque grin evoking horror-inspired imagery aside. But the 70s were an era of experimentation, dabbling in monsters, sci-fi, and even martial arts, pushing the limits of what could be included in a typical monthly mag even before the 80s took a battering ram to those boundaries.

After a single issue from DC horror series House of Secrets, Wein and Wrightson develop an ongoing story segmented into various unique chapters, each one entrenched in the horror genre's proclivity to help humanity see its darker, more disturbing corners and crevices. The opening House of Secrets issue introduces Alex Olsen, a precursor to Alec Holland, also transformed into a swamp monster who would play a role in Moore's run on the title. This may cause readers some confusion, but after this initial appearance (which, as Wein writes in an introduction to the volume, was DC's best-selling issue the month it debuted, generating tons of fan mail and convincing executives to encourage Wein and Wrightson to create the ongoing series), Olsen is gone with the snap of a moss-covered twig. Alec Holland debuts in the first issue of his monster's titular series, his origin is played out, and the focus is solely on him and his misadventures as a not-so-mindless monstrosity across the next ten installments.

Where Swamp Thing diverges from his closest Marvel counterpart, the similarly marshy Man-Thing, is his singular focus. Man-Thing–also a former scientist whose experiments led him to becoming a shambling swamp monster–retains little to none of his human intelligence, led by primitive emotions as he encounters evil. Fighting darkness is instinctual for the Man-Thing, not intellectual. Wein and Wrightson's creation keeps his capacity for thought, knows he was once the perfectly human Alec Holland (at least, prior to Moore's game-changing twist on his origin), and doggedly pursues a single-minded goal: to regain his humanity. Like the Hulk or (non-Swamp) Thing before him, the creature who was once Alec Holland desperately seeks to resume his former form, find life again, resume a normal existence as a man.

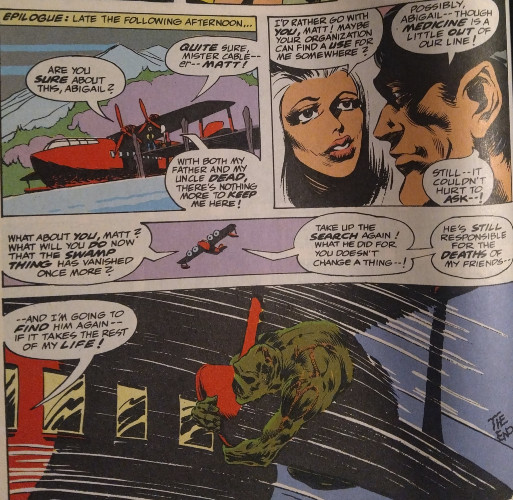

To this end, Wein and Wrightson wrap bitter ironies across the page, as in his quest, the monster finds himself with few allies. As he engages in his search, federal agent Matt Cable pursues him in the ignorant belief that Swamp Thing murdered his friend, the scientist Alec Holland! This cat-and-mouse game is woven marvelously throughout these issues, compounding the other conflicts Swamp Thing encounters: crazed villagers, mad scientists, a werewolf, creatures from other realms. Wein's words (and, at times, lack thereof) create resonant emotional impact, as Agent Cable's anger is met with silence from the marsh monster who can't hope to explain himself, have a conversation, convince anyone he was once a man. I wanted to reach through the page, shake Cable, make him see the red eyes of the Swamp Thing were also those of his friend. You hope the agent will come to his senses, make a connection, have a realization…but he does not. He keeps chasing, and we keep watching…and hoping.

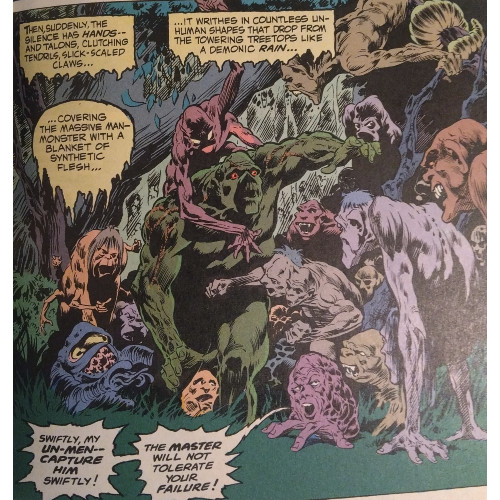

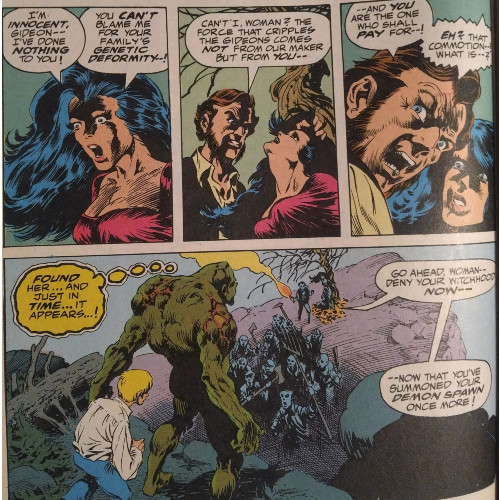

Wein impressively not only extracts humanity from the heart of this monster–aided by Wrightson's injection of emotion into Swampy's crimson peepers and occasionally distorted, agonized visage–but he capably finds monsters in the hearts of some humans. The characters Swamp Thing combats physically–like a misshapen patchwork man resembling Frankenstein and a slavering werewolf–are, at their cores, victims of circumstances they could not control, either abused or used by people with dark agendas or twisted righteous intentions. Folks who are truly evil suffer for their crimes, often at the hands of their victims, intended or otherwise. As in several pieces of horror fiction, the seemingly normal humans are the true abominations, scorning those considered different or ugly or seemingly dangerous but embracing their internal inhumanity by doing so. Religion, philosophy, science, politics, wealth...all can be used to further corrupt agendas to target the physically different. Evil is placed upon the shoulders of the disfigured and downtrodden, often unfairly, with Swampy becoming a silent champion for those abused and hunted.

They feel like parables, these issues, cautionary tales written to whatever youngsters or adolescents picked up the mags. Through the eyes of a man-turned-monster, we see other men and women distort themselves, becoming far worse than the things they fear. I was reminded of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's early X-Men issues, where Marvel's merry mutants served as a fairly shoehorned metaphor for race relations. Wein and Wrightson strip away any ham-fisted attempts at commentary to lay bare core concepts: hatred is wrong, good intentions can lead to unintended consequences, don't judge a man by his moss-massed body, and you don't have to look like a nightmare to behave abominably. They place Swamp Thing in dark circumstances–physically, emotionally, spiritually–and guide him through to the other side. If a monster can act better than most of the people he engages with, well, something must be wrong with how you're running things, isn't there?

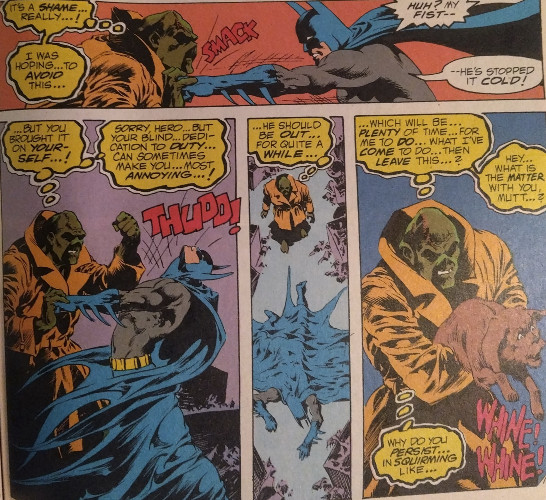

Though each issue largely stands on its own, save for a two-parter early in the series (thus enhancing the impact of each "parable" in short, rapid-fire stories), elements are nicely woven through to give these issues a sense of cohesion. I've already discussed Agent Cable's involvement, serving as a significant B Plot across Swamp Thing's misadventures, but brief appearances of a shadowy figure across multiple issues lends the overarching plot some additional heft. It's a plot point resolved by the end of this volume, allowing the transformed Alec Holland some closure on the events surrounding his transformation, even if the identity of the mastermind is far less intriguing than earlier issues indicate. The "wrap up" itself feels rather rushed, kept to largely the end of a late issue and roping in (somewhat needlessly) one popular Caped Crusader. But a villain faces their comeuppance, leaving Wein and Wrightson to devise a new direction for their mildewy marsh-man.

It's not a unique tactic, certainly. Moore himself would do the same years later for the Swamp Thing, offering a dramatic turnabout to propel a central character in a new direction. I fondly recall Chris Claremont employing a similar method with Iron Fist, taking over Danny Rand's adventures after a revenge story was completed and exploring where the hero could next turn. Wrap up one story, let another one begin. Claremont's expertise allowed him to plot new stories as he finished current plots, simultaneously providing satisfying conclusions while teasing the readers with what was to come. Wein does not employ the same tactic, and though it's interesting to see where he and Wrightson may direct Swamp Thing in the aftermath, we're given a few more of those "cautionary tales" before the volume ends. Aside from a clever plot twist near the volume's final pages, these stories represent the weakest portion of the collection, a little lost in the wake of providing a conclusion for one dramatic arc.

Wrightson, a famed horror artist as I noted, lives up to his reputation. Swamp Thing is equal parts repugnant and intimidating, a hulking brute rippling with muscle. He's not unkempt like his Marvel counterpart, but he's a monster with a few snaking vines for veins and piercing eyes. More distorted are other monsters which oppose the Swamp Thing, allowing Wrightson to play with deformed shapes, tentacles, and teeth. He illustrates skin well–gaunt in how it's draped over bones, stretched thin. His monsters are walking cadavers, deathlike in appearance. You know Swamp Thing is the series' hero because the mag has his name, he's the central character, etc. But if you needed additional convincing, Wrightson makes it clear that, in this series, Swamp Thing may be the least horrifying horror present.

Other issues of this original series have been collected in omnibus format, which I'm not a huge fan of, so I likely won't be reading much of Swampy's original adventures past this volume (though I do hope to slog through more of Moore's run…not that it's been a slog so far, I just thought the visual was appropriate). Wein and Wrightson, together, develop a character wholly unique in appearance and behavior, even if that uniqueness was eventually co-opted by the House of Ideas. Other writers would leave their mark, and Moore would completely upend the character's origin and purpose, but if all you want to read are these, they form a strong introduction to the Swamp Thing…just don't get stuck walking through.