Random Reviews: Saga of the Swamp Thing (Book 1) Review (Gods and Monsters, Part 1)

Alan Moore recreates a classic DC hero in issues truly fulfilling their "mature" label, for philosophical pondering if not for content

—by Nathan on August 3, 2024—

You gotta feel a little bit bad for Len Wein.

In 1974, in Incredible Hulk #180, he co-created a Canadian superhero with an eternal hangnail problem. Logan, the scrappy mutant with the healing factor and anger management issues, would go on to much greater heights under writers such as Chris Claremont and Barry Windsor-Smith. In 1975, Wein developed a brand new X-Men team, which would also be largely guided by Claremont during the next 17 years. For Marvel, Wein also contributed to the second-ever Man-Thing story, a seven-page section in 1972's Astonishing Tales #12, illustrated by Neal Adams.

And Man-Thing wasn't even the first muck monster Wein developed.

Swapping in "Swamp" for "Man-," Wein created the muddy monstrosity for DC alongside horror icon Bernie Wrightson. Initially popular, the crude creature's first series couldn't survive the changing of the guard and was canceled after 24 issues. Revived in 1982, Swampy's new series tacked on a “The Saga of” at the beginning and plodded along under a creative team which was eventually replaced by a then-up-and-coming creator brought across the pond from Britain: a young writer named Alan Moore.

I've never read the original Swamp Thing issues, either the creature's first shot at stardom nor the "Saga of…" issues preceding Moore's take on the character. Maybe I will someday, reaching into the mire and plucking out those older stories. For today's purposes, I plan to keep my hands clean, reveling in the newness which Moore injected into the series as he took a grimy, gritty concept and gave it a sheen which brilliantly undermined everything that came before.

So, with apologies to Len Wein, let me present to you…

Saga of the Swamp Thing (Book 1)

Writer: Alan Moore

Pencilers: Dan Day, Steve Bissette

Inker: John Totleben

Colorist: Tatjana Wood

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: The Saga of the Swamp Thing #20-27

Volume Publication Date: April 2012

Issue Publication Dates: January-August 1984

Publisher: Vertigo (DC Comics imprint)

In my first "Random Reviews" post, I noted how Vertigo publications would be kept separate from my main DC reviews in "Distinguished Critique," even though some of them inhabit the main DC universe, such as Saga of the Swamp Thing. Though Swamp Thing was originally published under the mainstream DC banner, eventually bearing a "Mature" label like more adult-oriented narratives such as Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters, the series is associated closely with the Vertigo line, hence its inclusion in "Random Reviews." To add to the complication, note the parenthetical in the title: "Gods and Monsters, Part 1." I am hoping to cover some of the comics which have seemingly inspired the first "chapter" of James Gunn's upcoming DC Extended Universe, called "Gods and Monsters," hence the additional tag on the title. As Swamp Thing filters into his plans, this feels like a good narrative to cover, even though most of those reviews will appear in–where else?–"Distinguished Critique." Is everyone thoroughly confused? Okay.

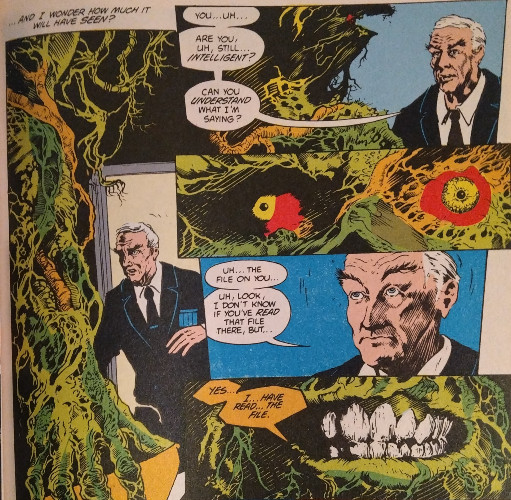

Moore's first issue, the tongue-in-cheek "Loose Ends," marks itself as a shift in the storytelling apparatus which preceded it. Though I am unfamiliar with prior Swamp Thing narratives, I can certainly grasp from other reviews or just a general understanding of the fandom at the time what a seismic shift it was for Moore to come aboard the title. From the jump, he dissociates himself from previous creators, wrapping up plot threads before quickly moving into his greatest contribution: a retcon of Swamp Thing's origin. In the remarkably written "The Anatomy Lesson," Moore uses plant-based baddie the Floronic Man (who we've discussed before on this blog) to uncover the monster's greatest secret: he is not Alec Holland, a man turned into a mulch monster. He is merely a mulch monster who believes himself a man.

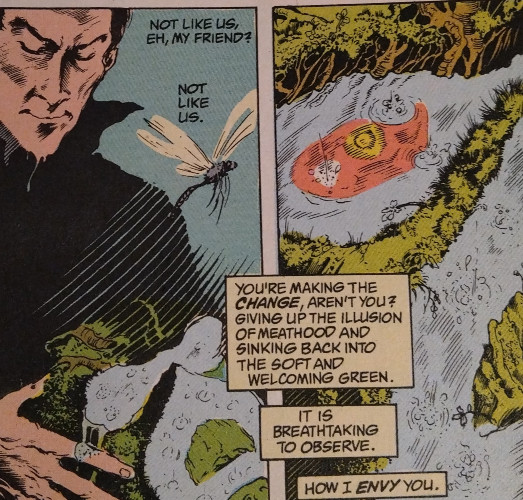

The ramifications are immediately apparent, and if Swampy's rampage through a laboratory isn't evident enough of his enraged reaction, perhaps his wallow through self-pity across the next few issues gets the point across. The twist is phenomenal, up there with Ozymandias' "I did it thirty-five minutes ago." It utterly changes the character's context, who he was in prior issues, and it obliterates who you believe him to be and what you want him to become. For the character's history until this point, he has been driven by a single goal, to reclaim his humanity. He wants to find the Bruce Banner within the Hulk, the Ben Grimm within the Thing. He's been just another Frankenstein-ian abomination who lost his humanity and desperately seeks to return to a normal life, shed of all his vines and tubers and leaves.

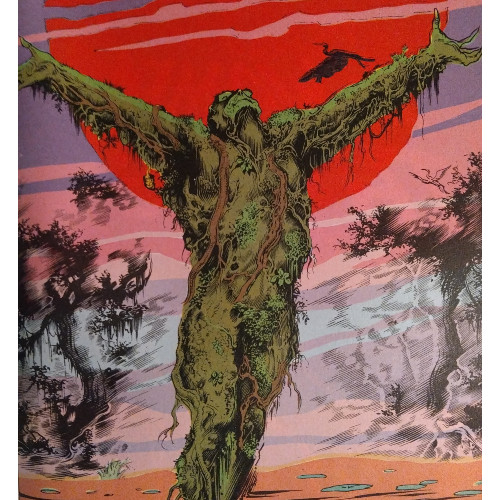

And now he can't have that. Because he is the vines and tubers and leaves.

Even if you're aware of the twist heading into the narrative (and I do apologize for spoiling a forty-year-old plot development for any reader unaware), the impact is hardly (anatomy) lessened. The build-up to the revelation is perhaps even more intense once you know the twist, as you sit in the suspense of Swampy learning the eviscerating truth and sharing with you in his tragic secret. You see his desperation and rage in a new light. You see him sink into himself, literally bonding with the Earth while his mind tears itself inside out as Moore forces him to reconcile with this emotionally obliterating piece of information. What's a Swamp Thing to do now?

Moore spends the issues filling this volume's second half exploring that notion. Now that he's thoroughly dragged Swamp Thing through his own emotional bog, Moore methodically picks up the pieces to instill in the marshy man-who-is-not-a-man a new purpose. "I want to…be alive," he tells a friend, successfully pulled from the depression which had inflicted his mind. It feels like something of a mission statement from Moore, that Swamp Thing is now set out to find what life means for him, not what it would have meant were he actually Alec Holland.

Moore strategically develops a narrative which is in opposition to the tried-and-true method of superhero comics. Moore is not creating another Batman who uses his trauma as a reason for punching demented clowns. The line of logic running from "I have these abilities" to "I should wear a costume, take a moniker, and punch villains in the face" is thin indeed, and one can see how other narratives from Moore, including Watchmen and Miracleman, defy that status quo instituted by genre trappings. Swamp Thing is a superhero in the narrowest sense, that he stars as the protagonist in a comic book and exists in a world where other heroes fly and fight crime. He'll rampage when the need calls for it or when he gives over to his more base urges, but he's more likely to tackle a problem differently.

If you think this is just a coincidence or a way to distinguish Swamp Thing from his compatriots, look no further than Moore's depiction of the Justice League. "The over-people," Moore calls the group of heroes as they sit in their superhero headquarters/space station and deliberate over how to stop the Floronic Man after he initiates a hostile takeover of a Louisiana town. Once they finally arrive, Swamp Thing has, through decidedly non-violent means, smoothed the entire situation over, leaving the League to pick up the pieces as he returns to his home. Swamp Thing is a caretaker, and though he might be called to bash a few demons and monsters, he seems to relish the calm and quiet, a stark contrast to the world (and the genre) he inhabits.

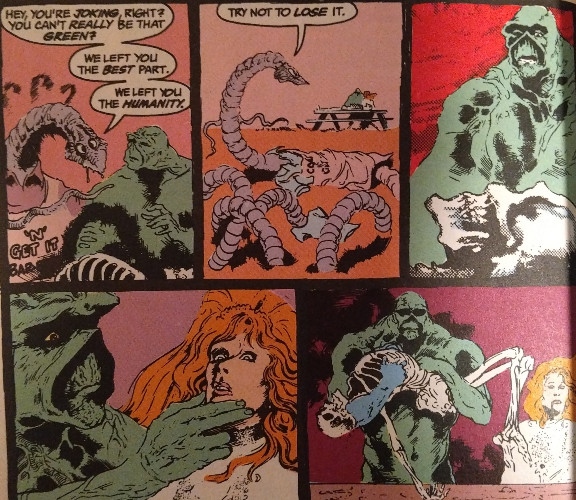

With the aid of Dan Day and Steve Bissette, Moore turns the title into a deliberately frightening slice of horror. Violence, yes, permeates the title, with people dying in all manner of horrible ways, from the agonizing process of suffocation to being on the macabre yet ridiculous receiving end of a falling swordfish. But more than bloodshed creates a stygian quagmire for the reader to wander through. It's the ideas presented here which offer the pages a darkened hue. A rather psychedelic dream sequence allows Bissette to toy with Moore's wording, much like Dave Gibbons' managed in Watchmen, developing parallels before dialogue and imagery. Swamp Thing carries around a skeleton representing his (Alec's) humanity, unable to let it go even as it becomes battered and broken, clinging to the hope it portrays while wrestling with the inevitable conclusion of its worthlessness. He stumbles across his (Alec's) body as worms feed on his remains; offered a nibble, Swamp Thing moves too slowly, missing his opportunity. Imagery and text align to double down on the concepts of humanity and identity, visually stripping Swamp Thing of both.

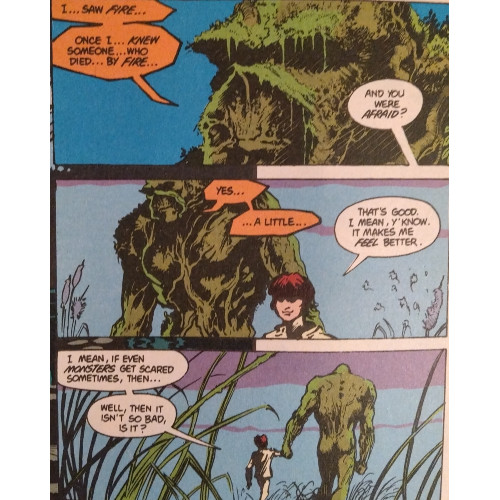

Our maligned monster is, quite wonderfully, presented as a sympathetic creature. Though Moore successfully extracts the creature's human origin, he imposes on us the belief that some form of emotion exists within Swampy. One would think, if the humanity was a mere mirage, so too would be the associated emotions, that Swamp Thing would discard those as much as he does his false past. But he doesn't. He remains, in the moments where he isn't violently and vengefully plodding against a foe, surprisingly conscious of his emotions, even connecting at one point with a young child. Like the Hulk, he's still a monster. Unlike the Hulk, he savors human contact…one piece of his connection to Alec Holland he cannot completely release.

Alan Moore’s reinterpretation of Swamp Thing is successful, paving the way for stories across the following four decades. I don't know how the rest of Moore's run shook out, though other volumes exist which I may have to consider examining. This is a strong narrative from the pre-Crisis years at DC, representing a writer whose beginning is equally as potent as his later work. It's my hope to explore other facets of the Vertigo side of DC Comics, other narratives which strove to redefine the concept of comics and pushed the envelope so the genre could envelop more readers than your average kid-centric series.