Random Reviews: Animal Man (vol. 1)

This collection brings Animal Man into a much-needed spotlight, blending heartfelt humanity with superhuman shenanigans

—by Nathan on April 29, 2025—

These days, Grant Morrison may be a household name, known for (among other things) We3, The Invisibles, a famed run on Justice League, a famed run on Batman, and All-Star Superman, which many readers hail as the best Superman story of all time (I personally give Superman: Birthright the crown, but I digress). But early on, Morrison wrote for several British publications, eventually transferring across the pond to DC Comics, armed with two proposals. One would eventually develop into a graphic novel focused on Gotham's favorite medical house of horrors, Arkham Asylum.

The other proposal…was Animal Man.

Morrison joined the "British Invasion" as creators such as Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Bryan Hitch, and Jamie Delano brought their brand of storytelling to America. While Gaiman reintroduced his version of the Sandman and Moore tore Swamp Thing down to his roots, Morrison took ahold of Bernard "Buddy" Baker–a character who had been around since 1965 but, prior to 1988, had less than twenty physical appearances, his last having been as a cameo during Crisis on Infinite Earths.

Like several of his DC counterparts, Animal Man was rebooted…though, unlike several of his DC counterparts, the argument that Animal Man deserved a reboot seemed far-fetched. Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Green Arrow, the Flash were all classic characters…heck, even Aquaman, by way of his longevity, seemed to deserve another shot in the wake of the Crisis. But Animal Man?

Like a vulture, Morrison swooped in, stripping the dead flesh off Buddy Baker to see what was worth scavenging beneath.

Animal Man (vol. 1)

Writer: Grant Morrison

Penciler: Chaz Truog

Inker: Doug Hazlewood

Colorist: Tatjana Wood

Letterers: John Costanza

Issues: Animal Man #1-9

Volume Publication Date: July 1991

Issue Publication Dates: September 1988-March 1989

Publisher: Vertigo (DC Comics imprint)

Grant Morrison can, at times, be a very cerebral writer, plots stuffed with concepts that would make Jack Kriby or Steve Gerber's heads spin. Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth requires multiple reads to understand the depth of references and allusions Morrison includes, and the writer's work often includes nods to esoteric themes and highbrow ideas. Morrison's imagination is vast and malleable in incredible ways, and though it shows itself here, these stories are more merciful to the reader. Maybe because this was Morrison's first long-running American assignment, Animal Man is graciously down to earth.

Not literally down to earth. Buddy often flies, soaring across the pages after lifting the ability from some nearby bird. But you know I meant that in a figurative sense anyway, so let's move on.

What makes these opening issues of Morrison's run so delightful is how grounded and charming they are…at least, to start with. The series' scope would escalate over time, but for these first few issues, we're nicely introduced to a seemingly simpler world. We don't begin with some mind-bending idea. We begin with a man, Buddy Baker, who believes his ship is finally coming into dock. He's considering becoming a Justice League member (which does happen later in the volume), and he's looking to secure television appearances and other ways to support his family. For so long, that burden has been on his wife, but Buddy feels he's in a place where his superhero gig can land him some additional financial solvency.

I don't know if Mrs. Baker and the two Baker kids appeared in prior issues, but where Batman was thrust fully into the darkness of his vigilante role and Wally West was reintroduced as an angsty young adult, Buddy being presented a father is a surprisingly wholesome spot for Morrison to establish the character. The set-up enables Morrison to blend the human and hero aspects of comics very well–Buddy has a house, but it becomes a target for at least one supervillain attack; he has a wife and kids, but their lives are thrown into turmoil from time to time. Ever move into a nice little suburban house and expect Martian Manhunter to show up at your door one day to help install state-of-the-art security measures? Ellen Baker probably didn't. And that theme–blurring the line where the reality of family life and the fantasy of superheroics divide–becomes prominent throughout this volume.

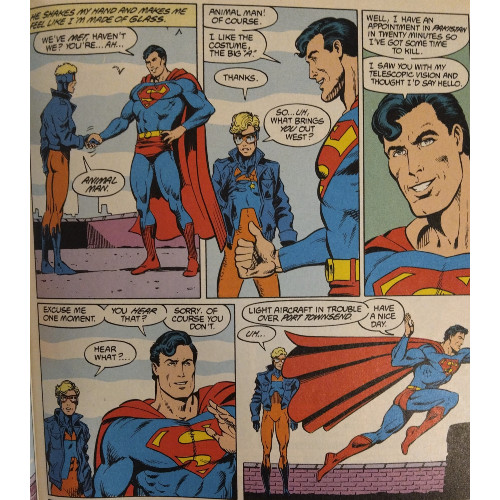

I know the word "meta" is thrown around a lot, but that's exactly what Morrison develops the title into, a commentary on its own genre. As I noted, it begins slowly, with its title character and his family aware of his faults and failings and seeking to grow beyond his predisposed placement as a B-list superhero. Buddy rails against being a has-been, of being mistaken for a guy like Aquaman, of having his name forgotten by a preoccupied Superman. He wants to be more than he's always been, more than just the guy who can absorb animal abilities. Where other writers may plop a character into a seemingly eternal status–Superman's always a Boy Scout, Spider-Man always a lovable loser–Morrison has the capacity to grow Buddy beyond his bare minimum qualities.

As a result, we come to care for and empathize with Buddy quickly. We don't always agree or support him–there are moments where he drives his wife Ellen up a wall–but that's part of what adds dimensions to the character. He can be a superhero and have a stable, if not occasionally disrupted, family life. But Morrison establishes Buddy as a hero we want to appreciate. We feel his frustration with being stuck in this "mid-life crisis" as a superhero without much clout, with being forgotten by or confused with other heroes, with having to take on unassuming assignments.

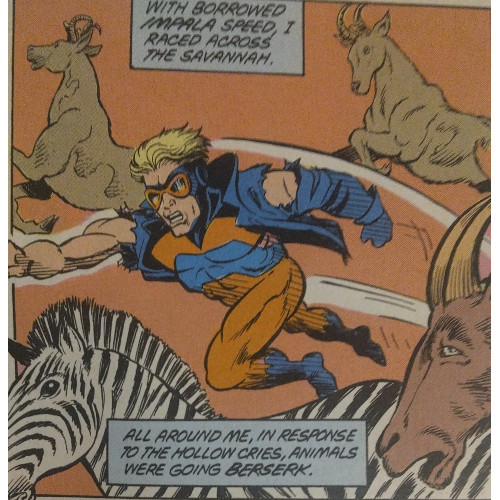

Morrison even works to heighten the character's name and abilities, moving him beyond how generic his moniker and powers appear. Anyone can make Animal Man swim like a fish and fly like a bird. But have you seen him adopt the regenerative power of earthworms to replace a severed arm? How about using inhuman strength to basically tear a creature in half? And let's not forget the time he absorbs a supervillain's ability to control animals and manipulates white blood cells to save someone's life. Morrison pushes the boundaries of Buddy's abilities, often to Buddy's own astonishment. And Buddy, embracing some of Morrison's principles, becomes a stalwart defender of animal rights. He's not just taking the fame and fortune route, he's seeking purpose…and maybe that means stopping an underground lab experimenting on primates or making his family eat tofu instead of meat products.

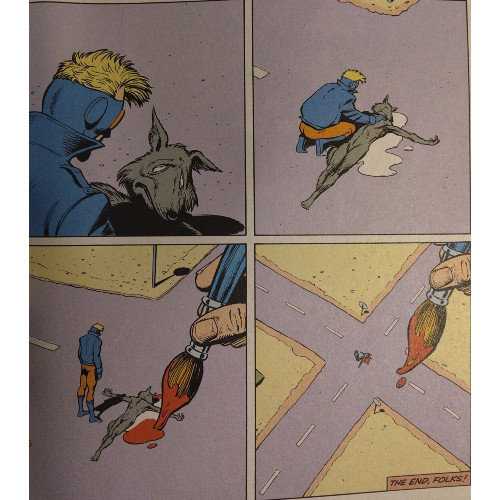

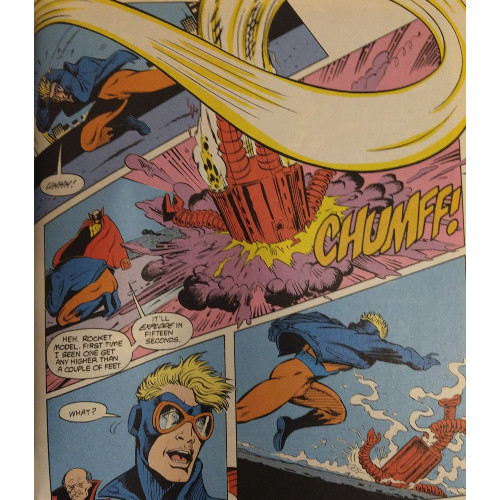

As Morrison stretches Animal Man, the writer also stretches the concepts littered throughout the series. This is art commenting on art, story commenting on the nature of stories. The series' fifth issue, titled "The Coyote Gospel," considered one of the high points of Morrison's run, centers on a Looney Tunes-esque coyote brought from a cartoon world into Animal Man's reality, regenerative abilities intact. What follows are desperate attempts to kill this seemingly unkillable creature, repainting the hilarious hijinks of Looney Tunes cartoons with a deeper horror. You watch Wile E. Coyote get crushed, blown up, and mangled, and you laugh, partially as a response to deflect the bodily horror such injuries would cause, partially because you know he'll return, whole, a few seconds later. The plot will never change, you know there is no escape for wily Wile E. Dark as that sounds, the grim nature of his existence is perfectly glossed over.

For Morrison's Coyote analog, named "Crafty," a stark shadow is enmeshed in his existence in our (or what passes for our) reality. He seemingly cannot die, so he endures bullets and trucks and boulders, only to stitch himself back together again. Pretend you were aware of each bone Wile E. Coyote repairs, each tendon he retethers, each muscle he regrows. Takes the fun out of it doesn't it? And this is Morrison's point: dredge up the grim reality of the story, of your character's inescapable fate, and the charm is replaced by stark reality, adding a finer edge to your art.

You see it, in these issues, in a Silver Age villain, dying of an illness, who unleashes one final rampage on a city while contemplating suicide. You see it in B'wana Beast taking his frustrations out on a scientist experimenting on animals through a dark application of his superhuman abilities. You see it in a Thangarian artist, in a tie-in to DC's Invasion! crossover event, who creates a world-ending bomb connected to his memories so humanity can witness his achievements and failures before their ultimate demise, his life flashing before their eyes. What, under other storytellers, could be used for goofy or silly narratives is darkened by Morrison's brush. Morrison is the writer here, Morrison is in control. It doesn't matter what came before; that can be torn out and replaced with a world where Animal Man has to rely on absorbing earthworm abilities to keep himself from bleeding out in a back alley.

Does it work? I think so. I would probably never have read an Animal Man comic before this series (not that, it appears, there were many to choose from…), but the application of serious, mature moments heightens what Morrison is creating and makes Buddy Baker's adventures worth reading. How much more basic could you get than attaching the word "Animal" to "Man" in a superhero name? There's just not much appeal. But having the character grow up a little bit, experience this mid-life crisis while juggling raising a family with saving San Diego from an anthrax-infected simian or rescuing the world from a winged poet/terrorist, allows for more development and interest in the character. Buddy's just trying his best, even if nobody knows him or always agrees with him.

It would be unforgivable to review this volume and not at least touch on Morrison's most important supporting cast members, Buddy's wife Ellen and their two kids, Cliff and Maxine. As I noted, they are thrust into a life teetering between the fantastic and the fearful–it's awesome when Martian Manhunter can scare some bullies bothering Cliff; it's not as awesome when Cliff trips the home security system and is nearly fried by a laser cage. The three become embroiled in their own misadventure early on, reinforcing some of Morrison's animal activist sensibilities while also placing the trio in a genuinely dangerous situation (one which actually doesn't involve Buddy and forces them to find their own way out). How they face the problem, and how they react to not only this event but other occurrences, fortifies the balance between the human and superhuman aspects and the twin natures of the series' lighter touches and grim undertones. There's a sense Buddy walks a thin line between what's real and what may be fantasy, and it's his family which anchors him to reality, reminding him why he does what he does but cautions him from taking steps too far. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in an issue where Ellen fends off the Mirror Master and saves Buddy from the villain's mirrored dimension, literally bringing Buddy back to reality. Morrison nicely allows these three from becoming stagnant. They're active participants in Buddy's future, weaving their own fate as they're drawn further into his.

As Animal Man would become a Vertigo title, I slotted this in "Random Reviews," but we're firmly in the DC side of the comics multiverse. I noted this series effectively "rebooted" the character much the same way other creators reintroduced the world to Superman, Batman, Green Arrow, Wonder Woman, and the like in post-Crisis continuity.. Consider this a sly continuation of my exploration of post-Crisis reimaginings under a slightly different identity…and consider Morrison's Animal Man one of the better reinterpretations of a character I've read so far. I know we're only nine issues in, but this ranks up there with work done by Frank Miller, George Perez, and John Byrne. The series is heartfelt, grounded yet tinged with wackiness, and promising much more weirdness to come, all the while wrapped around a character whose powers are so tied up in absorbing abilities from other lifeforms he sometimes needs a little help remembering the "man" in the latter half of his name.