Random Reviews: Magnus, Robot Fighter: Steel Nation

An infamous executive returns to the comics industry by reintroducing a Golden Age superhero in a surprisingly entertaining batch of issues

—by Nathan on March 30, 2025—

In 1987, Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter was dismissed from the House of Ideas. He didn't step down, as some early reports suggested. He was fired and replaced by Tom DeFalco.

Shooter's time at Marvel was a contentious one. Sure, he oversaw financially successful story and run after financially successful story and run, and several of the narratives produced during his tenure–"The Dark Phoenix Saga," Walt Simonson's Thor, "Born Again" in Daredevil, even Shooter's own Marvel Super Hero Secret Wars–remain impactful and continue to be read widely today. But Shooter had a big head, and his way of doing things often rubbed folks the wrong way. He truncated Roger Stern and John Byrne's Captain America run, followed up Secret Wars with an infamous sequel, failed to hold on to top-tier talent like Frank Miller and Doug Moench, and allegedly once suggested the possibility of killing off the Marvel Universe's main heroes to replace them.

Like Marvel would ever replace their best heroes!

So Shooter was eventually shown the door, but that didn't mean he was out of the comics biz for long. After a failed bid to buy Marvel, Shooter put his funds into starting up a brand new company in 1989: Voyager Communications, the comics-publishing arm of which was called Valiant Comics. The company has had its ups and downs, as far as I'm aware, and though I'm not educated on the details, I know they continue publishing material today. But when they started producing comics in 1991, Shooter, along with talent he poached from Marvel such as Bob Layton and Barry Windsor-Smith, needed to begin somewhere to construct a burgeoning universe.

Thus, the Valiant Universe was born from a menagerie of ideas: some of their heroes would be assembled from pure imagination, others lifted from Gold Key Comics. One of those Gold Key acquisitions kicked off the infant universe: a robot-fighting, red mini-skirted warrior known as Magnus. Ever since exploring the origins of the Image Comics universe, I've wanted to dive into the beginnings of other independent companies. How did early attempts by creators, particularly those in the late 80s/early 90s, thumb their noses at the Big Two by doing what few companies had done before–creating heroic legacies not fronted by characters with "Spider," "Super," or "Bat" in their names? These former Marvel employees, hoping to make a mark on the industry without working for "the man," took risks, forging their names across new titles. No longer did Jim Shooter's name appear by the "Editor-in-Chief" credit on Marvel's comic splash pages. But it would appear somewhere else, with a character who wasn't his own creation but on a story that would be.

Magnus, Robot Fighter: Steel Nation

Writer: Jim Shooter

Penciler: Art Nichols

Inkers: Bob Layton, Kathryn Bolinger

Colorists: Janet Jackson, Karen Merbaum

Letterer: Jade Moede

Issues: Magnus, Robot Fighter #1-4

Volume Publication Date: October 1994

Issue Publication Dates: May 1991, July-September 1991

Publisher: Valiant Comics

Predating Image's first issue of Youngblood by approximately a year, Magnus, Robot Fighter #1 brought a new spin on a hero who'd been around for decades. How Jim Shooter and Art Nichols' vision jived with previous versions of the character, I'm not aware–I don't know what history or continuity they kept intact versus what they discarded. I entered this volume fresh, fully oblivious to the character's prior history (as I am with another of Valiant's acquisitions, Solar, who I'll discuss in a later post or two), but hoping to enjoy a fairly standalone narrative developed by an industry legend.

And, somewhat surprisingly, I did.

I'll admit to beginning the narrative as a skeptic. My foray into the Image Comics universe's less-than-stellar opening salvo of titles left me beyond frustrated, and the thought of leaping into the maw of another 90s independent publisher became a task I didn't quite relish. I certainly anticipated that Shooter and Co. could produce a better narrative than Liefeld and Friends, but I held out on hope. Add in Shooter's tenuous writing capabilities as I have previously experienced them–as much a guilty pleasure as the original Secret Wars is, it's not the most brilliantly written narrative, and Secret Wars II is an absolute mess–and I cannot say I had the highest expectations.

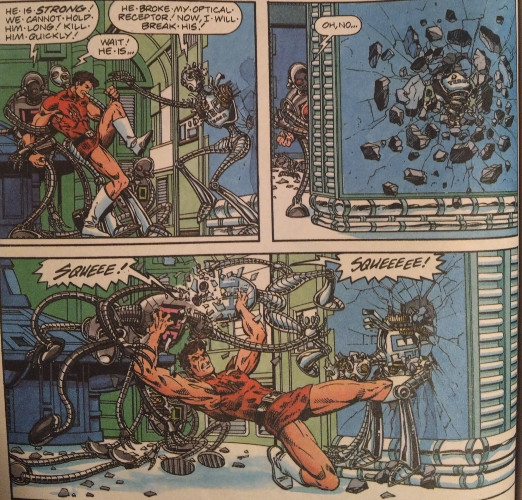

In this opening arc of Magnus, Robot Fighter, aptly titled "Steel Nation," Shooter displays fairly solid writing chops–the dialogue is straightforward, lacking the exquisite poetry of creators such as Chris Claremont and Don McGregor, but providing a decent pace which prevents any scene from lingering too long. Pageantry would be inappropriate from Shooter, whose tone here emphasizes action-packed pacing once we sift through an opening section dedicated to exposition. Gone is Shooter's "any comic could be somebody's first" mentality, which I thought bogged down several issues produced during his tenure at Marvel, allowing him to maintain movement throughout "Steel Nation."

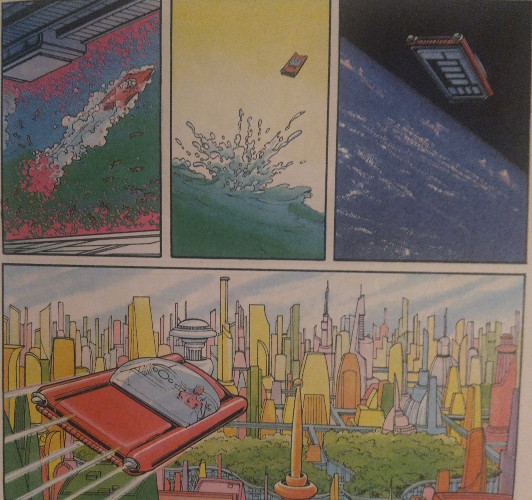

These issues echo the same kind of quality found in Marvel's earliest original graphic novels, such as The Death of Captain Marvel or God Loves, Man Kills, primarily in the artistic skill Art Nichols displays (and with a first name like that, I'd be disappointed if this book didn't look good!). His is a nice blend of older sci-fi era designs with some graceful fluidity in character construction–his Magnus is powerful without coming off as awkwardly bulky, his robots somewhat cheesy and clunky while working as believable threats. Colorists Janet Jackson and Karen Merbaum help infuse a futuristic world with beautiful vibrancy. North Am is a world that feels somewhat similar to Marvel's own foray into the future in their 2099 line, both aesthetically and structurally–like the New York of 2099 (or even the Thanagar of Timothy Truman's Hawkworld), the pristine city Magnus inhabits is built directly above/atop its slums, creating a pretty significant divide between the "haves" and the "have-nots."

In that vein, Shooter is surprisingly tame when it comes to discussing this divide in the narrative. There is social commentary here–the main robotic antagonists wish to assert their freedom by rebelling against their masters–but Shooter spends little time calling out the clear economic dysfunction which inhabits North Am beyond his portrayal of its affluent, aloof upper class. This is not a sharp critique–which, again, would feel tonally inappropriate–but the subtleties displayed through the art create a pervasive sense of luxury and wealth which the well-to-do feel protected by…and find they're failed by when robots rebel. Several wealthy folks cavort at an anti-gravity dance club while fires break out in buildings around them and the news reports robot advancement. Magnus is invited to a dinner with his girlfriend and her father, attended to by robot servants, discussing the robot uprising all the while oblivious to the potential evils around them; the tone deaf criticisms of wealthy men besmirching the very automatons which serve them adds a humorous angle to the proceedings (also calling to mind a specific scene from Hawkworld) while not undercutting the principal message. You don't feel like Shooter is critiquing any one person in particular–though somewhat obvious, he's not as blunt as he was with his self-insert hero in Secret Wars II–confining his nose-thumbing to a general class of people. Wealthy folks, people in charge. Fairly safe groups of people to throw a winking barb at periodically, primarily instigated by Art's art.

This conflict created between humanity and its former autonomous servants delivers a unique thematic notion. Many of these robots are given an additional spark of life, which causes them to think freely, separate from the commands they've been programmed with. Server bots no longer wish to serve, gardener bots no longer garden. Through Magnus, Shooter asks the question: are these robots truly alive? What would it mean for them to have life, and in asserting their newfound self-awareness, are they claiming a right they truly have? The question of whether the robots really exist, even though they're capable of acknowledging an increased sense of self, runs prominently through the narrative. The idea affects Magnus himself, forcing him to wonder if wading through waves of robots is the best solution.

We find our hero often torn internally even as he tears through metal enemies. Magnus is, it seems, the most self-aware person in all of North Am, and even though other characters such as his girlfriend, the quasi-telepathic Leeja, are willing to help, they seem oblivious to the root of the conflict Magnus experiences. Like with the setting, I found myself comparing the hero of "Steel Nation" to Katar Hol in Hawkworld, who similarly experienced disquiet with the status quo. The concept isn't new to sci-fi/dystopian fiction, certainly, as novels such as 1984, Fahrenheit 451, and a whole slew of young adult novels can attest. If any difference exists, it's that North Am is not a strictly totalitarian nation (at least not in the eyes of its human inhabitants). Magnus does not fight to overthrow the government…but he does not completely agree with how the world around him is run either. This dual conflict–Magnus struggling to uphold the principles of the nation he fights to defend–lends some uniqueness to the premise, allowing these earliest Valiant issues to stand out from the legions of Marvel and DC books lining comic store shelves.

I'm not aware of the immediate impact Valiant's earliest releases had on the comic publishing industry. I know the first issue of Magnus, Robot Fighter sold 90,000 copies, enough for Shooter to see possible sustainability in his new line even if such numbers weren't going to break any records (especially considering Marvel's X-Men #1, by Chris Claremont and future Image co-founder Jim Lee, sold over 8 million copies the month after "Steel Nation" wrapped up, becoming the highest-selling single issue of any comic ever to this day). But these first five issues represent a fairly solid beginning to a comic franchise which continues to today–sure, the modern Valiant Universe is a reboot of what came before, but Shooter and Nichols lay the foundations here. I look forward to exploring some other corners of the burgeoning Valiant Universe, with far more gusto than I approached the origins of Image.