Spider-view: "Remote Control" (Spider-Man 2099, Part 8)

A simply told tale digs at some universal, yet brutal, truths

—by Nathan on February 7, 2026—

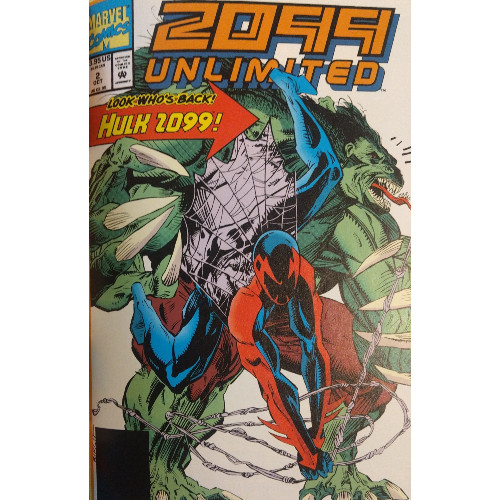

A short while back, I reviewed a two-part narrative by Evan Skolnick and Chris Wozniak featured in a "companion" title to Spider-Man 2099 called 2099 Unlimited. Where mainstream Spidey Peter Parker had received his own "Unlimited" series as a fifth Spidey title, with the first two double-sized issues opening and closing the 1993 crossover event "Maximum Carnage," Miguel O'Hara was asked to split his own page count between himself the the future's version of green rage monster the Hulk. Therefore, we're looking at one half of an anthology issue today.

Those two 2099 Unlimited issues told a cohesive narrative, with this somewhat bizarre second issue serving as a break in the middle. Today's Unlimited issue has nothing to do with Skolnick and Wozniak's two-part tale, yet like the other narrative focused on a serial killer murdering genetic deviants, this issue, too, wishes to ask the question of what happens when scientific and technological advancement is used for insidious purposes.

"Remote Control"

Writer: Evan Skolnick

Penciler: Chris Wozniak

Inker: John Lowe

Colorist: Kevin Somers

Letterer: Dave Sharpe

Issues: 2099 Unlimited #2

Publication Dates: October 1993

You can develop all the technological wizardry you can dream up, unlock all the scientific secrets there are to discover, create marvelous cities with holographic assistants, flying cars, and the promise of constantly better tomorrows…but you'll never completely annihilate the festering sore of human evil. The concept might feel regurgitated across media, but for sci-fi explorations of the future specifically, it's meant to be profound to a certain degree, emphasizing our collective propensity toward selfishness while allowing us more elaborate ways to perform cruelty.

Though, as Skolnick and Wozniak point out, some of the simple ways still work in 2099.

I don't mean to be a downer, drubbing humanity's turn towards darker inclinations. I believe each person has the capacity towards acting well and acting wickedly, but I also believe that left to our own tendencies, we'll take the rock-strewn waterways, guided by the siren songs of our hopes and dreams. It's what carries a decent number of folks in this issue, particularly our two primary antagonists.

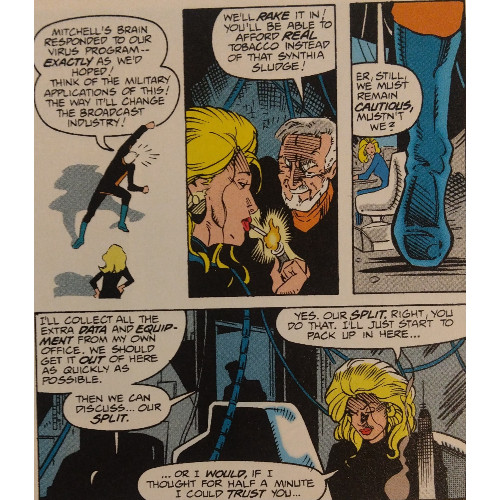

There are no supervillains in this issue, not really. Spidey does battle a few mercenaries decked out with some high-tech weaponry and cheesy, 90s codenames (Poncho! Recoil! Tarp!) who never appear after this issue, but our main antagonists are a couple of brilliant, morally misguided inventors. Developing a virus which hijacks the human brain and makes it susceptible to manipulation, the pair see dollar signs and discord…and they're not too keen on splitting the money.

We don't learn much about them, other than one used to work with our hero Miguel and thus uses the process on him to try and kill her partner…unknowingly involving Spider-Man in the whole business. They're devious and deceitful, these inventors, willing to abuse others with their latest invention and twist people to their liking. One inventor demonstrates their newfound code by applying it to a former coworker, having the man kill himself after losing all sense of control over his own actions. It's a cruel act, made all the more disturbing by how mundanely it's handled.

There is something to be said for the technology used–it's a program these two have developed, played through screens directly into the brain. It's advanced enough to feel like the product of a future civilization yet practical enough to imagine as a possible form of torment in our present reality. Computers? Check. Computer viruses? Check. The ability to adjust brain chemistry and DNA? Check. We've not yet managed to put it all together in the form Skolnick and Wozniak develop, but the pieces are laid out in front of us. And I'm not saying it's going to happen, nor am I advocating for the destruction of personal computers or the erasure of the internet for fear of this exact scenario playing out. There's a difference between "possible" and "plausible," and Skolnick writes this in a way that tickles the "plausible" side of belief.

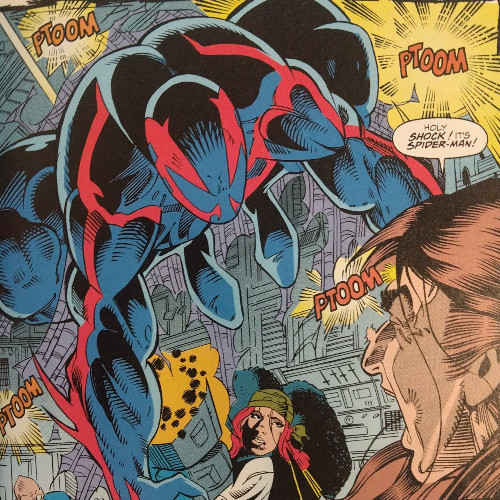

Yet even without the creepy, hijacking computer virus, Skolnick and Wozniak write evil in other forms. The issue opens with Miguel rescuing a woman in an alley from some muggers, a scene readers have watched play out in hundreds of comics previously. It doesn't matter than the muggers are using laser knives to scare this woman and fight Spidey–they're still muggers, looking for money, in a dingy alleyway. Miguel even comments on how there's no cure for what he calls "this disease," rampant criminality, even in a world where scientists are pulling apart DNA to cure other illnesses. Someone is later bludgeoned to death with a statuette of the Empire State Building, an old edifice, a "relic" as the killer calls it; a symbol of bygone days is used to brutally dispatch someone, an old form of murder used by someone giving into their base emotions.

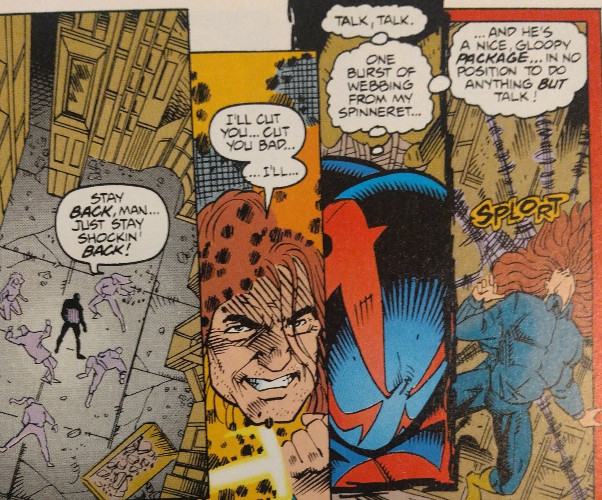

Even with his brain scrambled, Miguel is presented with a will of steel, fighting this programming to have his decision-making outfox the commands he's receiving. He's the hero–we know this, we know he won't succumb to this digital influence fully or for the entirety of the issue. Skolnick weaves in enough of a struggle to make Miguel's ultimate victory over this viral hypnotism achievable and believable. No deus ex machina moments or sudden strokes of luck or coincidence bring him out of this manipulation; he must make the choice for himself and does so in a manner which feels fitting for the narrative.

I wouldn't call this a standout issue or consider it a favorite narrative by any stretch of the imagination–and, please, no one write a brain-hijacking code and send it to me through an email to force me to change my mind–but this has a gritty charm to it. The issue is dark and relevant, blending futuristic technology with an inner torment that has plagued humanity since its inception. Seeing someone whacked over the head with a statuette is more frightening than a thug with a laser knife, precisely because it can happen now. I don't doubt the possibility of laser knives popping onto the scene at some future date, and I'm certainly not discounting the threat inherent in intentionally wielding an actual knife violently, but the bludgeoning feels a bit more relevant to today.

At the end of the issue, Miguel notes the dangers of living in a world "where everything's under control," and this has a clever double meaning. In one way, he's referring to the experience he just had, the ability of someone wielding their will over him. In another way, he's referring to the sheen the future has created, that everything is "under control." Maybe it appears that way, what with the shiny skyscrapers and flying cars. But make no mistake: perfection is a mirage, so long as people, even the people of 2099, remain imperfect. You can't throw us far enough into the future or give us enough advanced technology to cure that particular illness.