(Strand)om Stories: Sub-Mariner and the Original Human Torch Review

This volume features one hero floundering in a repetitive past and a second operating more organically

—by Nathan on February 17, 2026—

As I mentioned in my recent review of Fantastic Four #4, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby dug into Marvel's Golden Age to pluck that issue's antagonist from time, reusing a character who first appeared when (then known as Timely Publications) the company published its first-ever comic in 1939, the prophetically named Marvel Comics #1. The issue featured the first appearances of both Prince Namor the Sub-Mariner (by Bill Everett) and the android version of the Human Torch (by Carl Burgos), who would headline their own World War II-era titles and eventually, years later, be pulled into the Marvel Universe proper alongside Captain America.

In 1989, the company (no longer known as Timely Publications, in case you were concerned) elected to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Marvel's first comic, and Namor's first appearance, through two means. The first was the multi-part crossover epic Atlantis Attacks, spread out across fourteen annuals, pitting several of Marvel's heroes and teams against the forces of Lemuria (and I'll note I use the term "epic" purely ironically). Each issue came with a backup strip detailing the history of that narrative's McGuffin, the Serpent Crown. But in case those pieces didn't slake the thirst of any history-loving bibliophiles, worry not: Marvel had a whole other ocean for you to slurp up like panting dogs.

Their second effort was The Saga of the Sub-Mariner, a limited series reprinted in the volume I'm reviewing today (published to commemorate Marvel's 75th anniversary). Retelling Namor's extended history, from his first appearance to 1988's Avengers #293, it's nearly fifty years of history covered in twelve issues, courtesy of Roy and Dann Thomas and Rich Buckler. Because I just reviewed Namor's first Silver Age appearance, I wanted to dive in to this volume, which contains not only the Sub-Mariner's saga but a companion series focused on Jim Hammond, the man who bore the name "Human Torch" years before Jonathan Spencer Storm was irradiated by cosmic rays.

Sub-Mariner and the Original Human Torch

Writers: Roy Thomas and Dann Thomas

Penciler: Rich Buckler

Inkers: Bob McLeod, Roy Richardson, Mike Gustovich, Danny Bulanadi, Alfredo Alcala, and Romeo Tanghal

Colorists: Michael Higgins, Bob Sharen, Gregory Wright, Steve White, John Wilcox, and Nel Yomtov

Letterers: Joe Rosen, Jean Simek, Agustin Mas, Janice Chiang, Tim Harkins, and Jim Novak

Issues Collected: The Saga of the Sub-Mariner #1-12, The Saga of the Original Human Torch #1-4

Volume Publication Date: October 2014

Issue Publication Dates: November 1988-October 1989, April 1990-July 1990

Though this volume collects two series, the issues within are based on many other comics published across several decades, including issues of Marvel Mystery Comics, Sub-Mariner Comics, Young Men, Invaders, Fantastic Four, Avengers, X-Men, and Super Villain Team-Up. I waded into this volume thinking I'd be bored for sixteen whole issues of summary as the Thomases and Buckler detailed the histories of Marvel's two oldest heroes (if we're excluding, of course, the original Angel and the Masked Raider, who also debuted in Marvel Comics #1–where are those guys' twelve-part limited series???). Fortunately, I didn't reach the end of these sixteen issues wiped out by ennui, though my emotions were a bit more complex than I would have originally assumed.

The Thomases understand the laborious task in front of them, covering the adventures of two fifty-year old characters in just a handful of issues each. To their credit with the first series, they do their absolute best to make sure they largely hit the highlights of Namor's career, finding common threads, characters, and events across decades of stories to provide a more complete understanding of who Namor is, who his people are, and the events which have shaped him as an individual. The Thomases don't have as far along to go with the Torch, following Jim Hammond's career as an android/superhero/cop for quite a shorter distance, which is ultimately to their benefit.

The problem with the way Namor's history is presented in these issues has absolutely nothing to do with the Thomases–Roy Thomas is a celebrated creator, and even if he isn't always my favorite writer, he wrote some strong material in his day. It isn't even that the concept of who Namor is, a prince born of two worlds, makes for a lousy character. Namor should be interesting–he should be allowed to struggle with his identity and purpose. Like royal counterpart the Black Panther, Namor should be tasked with addressing both his own needs and those of his people. The Thomases also understand this…the failing is found in other writers.

I don't know how Roy and Dann Thomas put this series together, if they read a gazillion comics from the Golden Age and then checked over Namor's Silver and Bronze Age appearances to find complimentary material. You can tell they desperately try to hone in on recurring plots and points to craft a story over decades of development at the hands of different creators. The Thomases marshal their creativity as best they can, but they constantly run into the faults of other writers who return, time and again, to the same tricks in unfolding Namor's narrative.

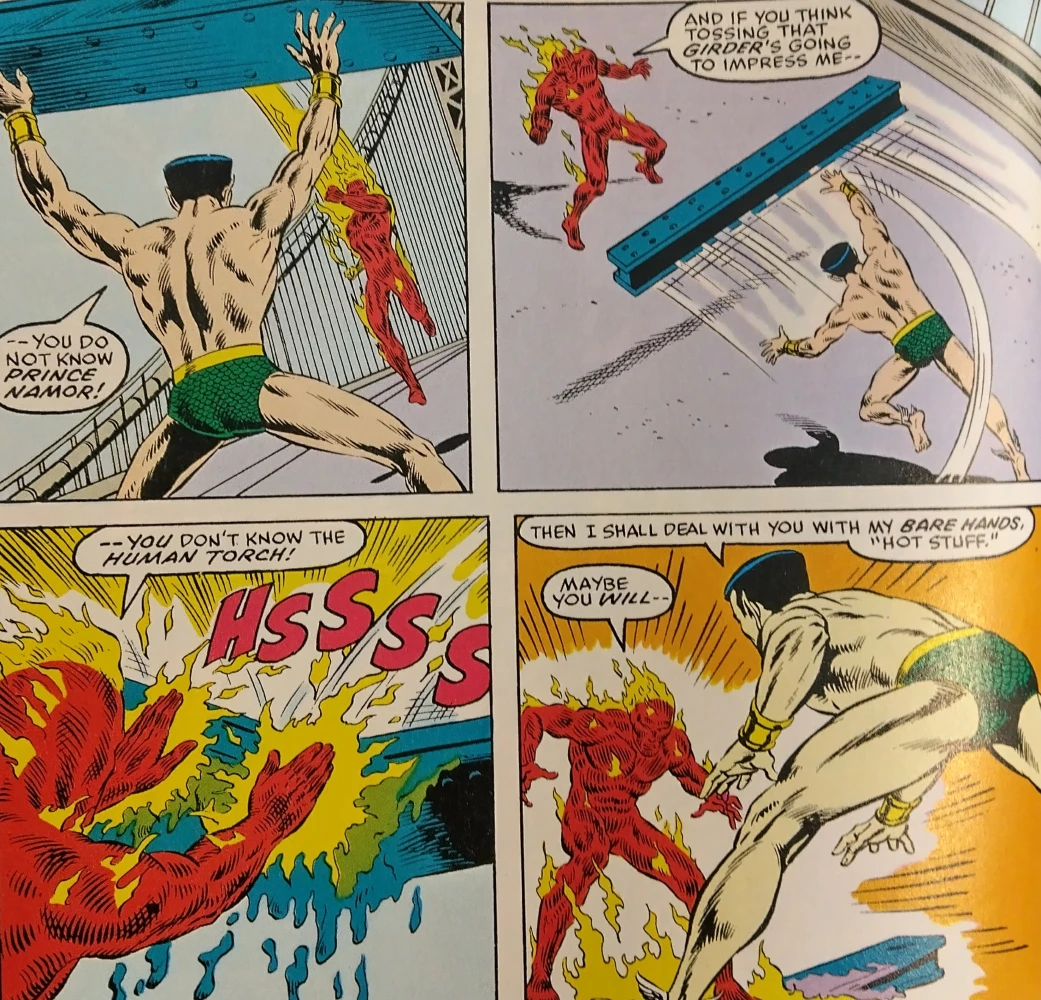

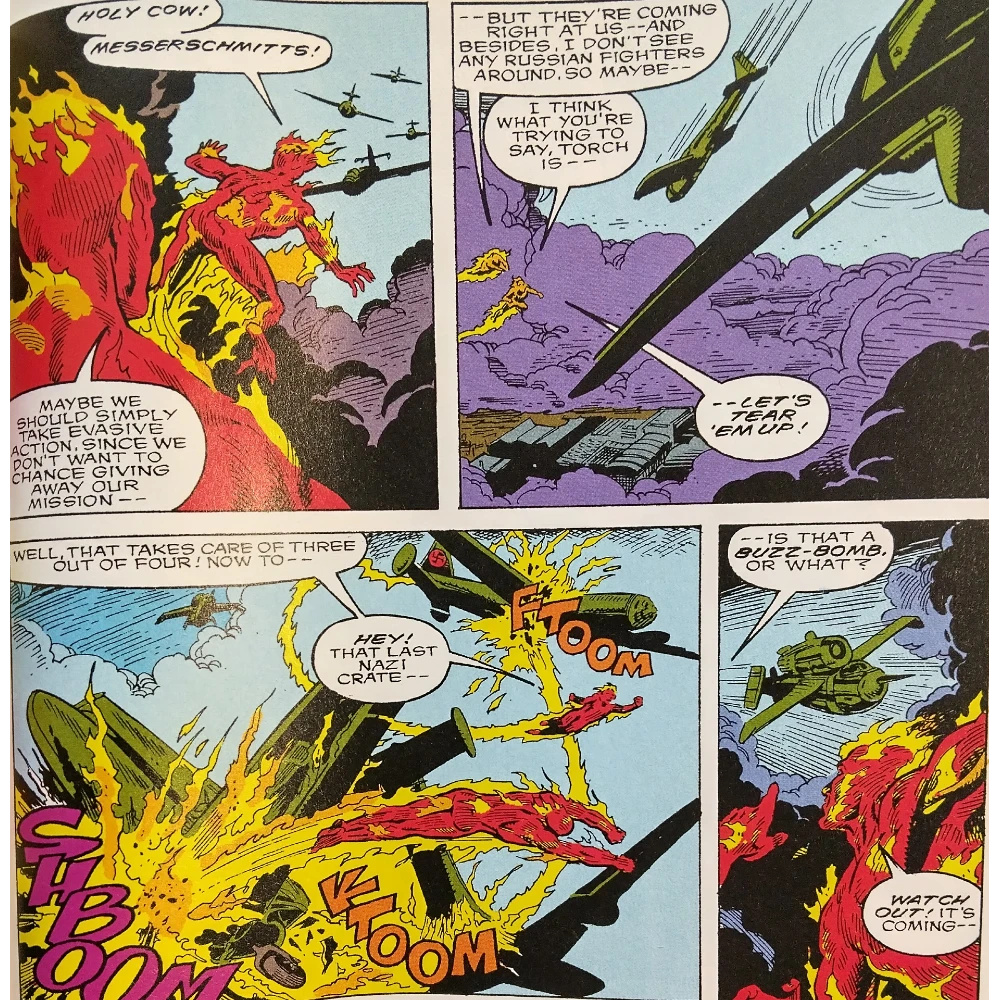

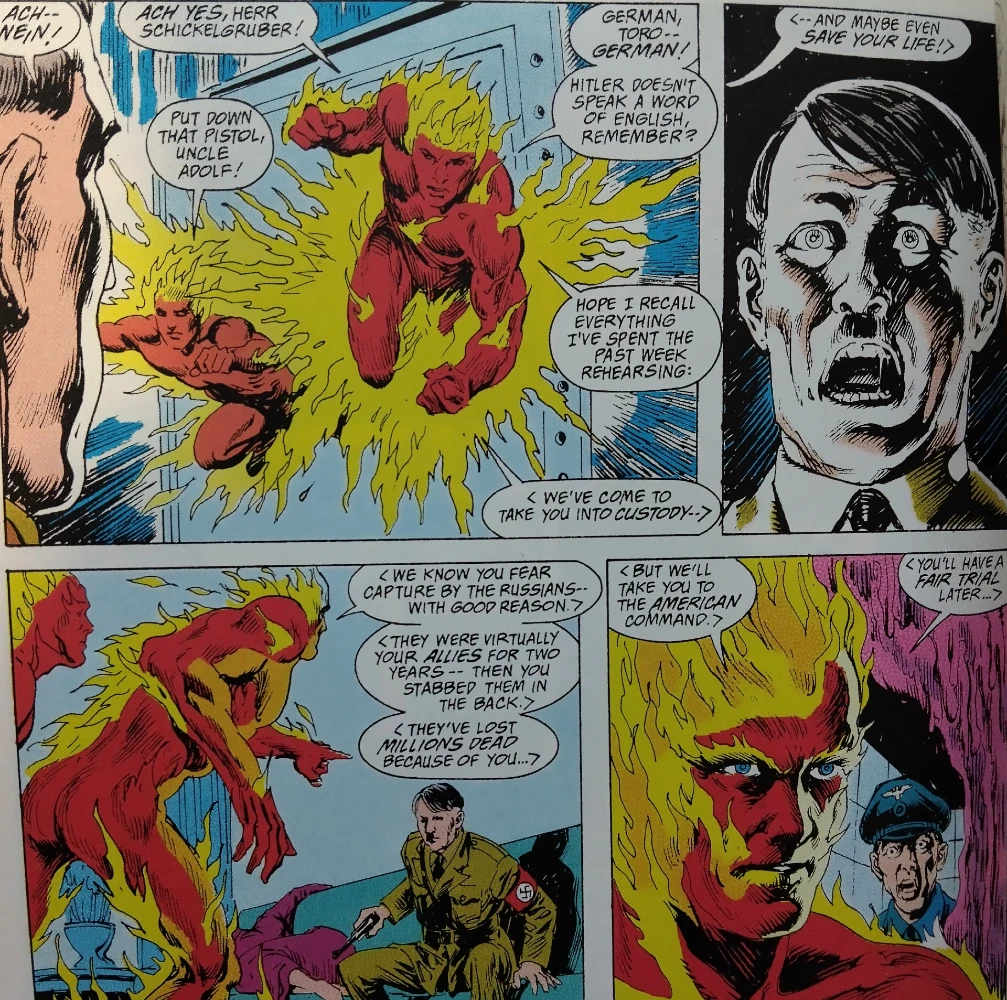

Unaware as I am of Namor's history, I never found myself laid out by boredom–the first few issues actually do a decent job at detailing Namor's past and the history of his parents and people, illustrated majestically by Buckler. He takes these Golden Age characters and locations and gives them a necessary polish, imbuing Atlantis with significant detail and moving New York through the decades. Especially in the Torch issues, Buckler shifts expertly into "period piece" mode, drawing us into the 40s and 50s and grounding us in actual events. Such grounding gives those latter issues more heft, though the creators don't skimp on the details when Namor attacks Nazi submarines and faces the threat of nuclear devastation against his people and city.

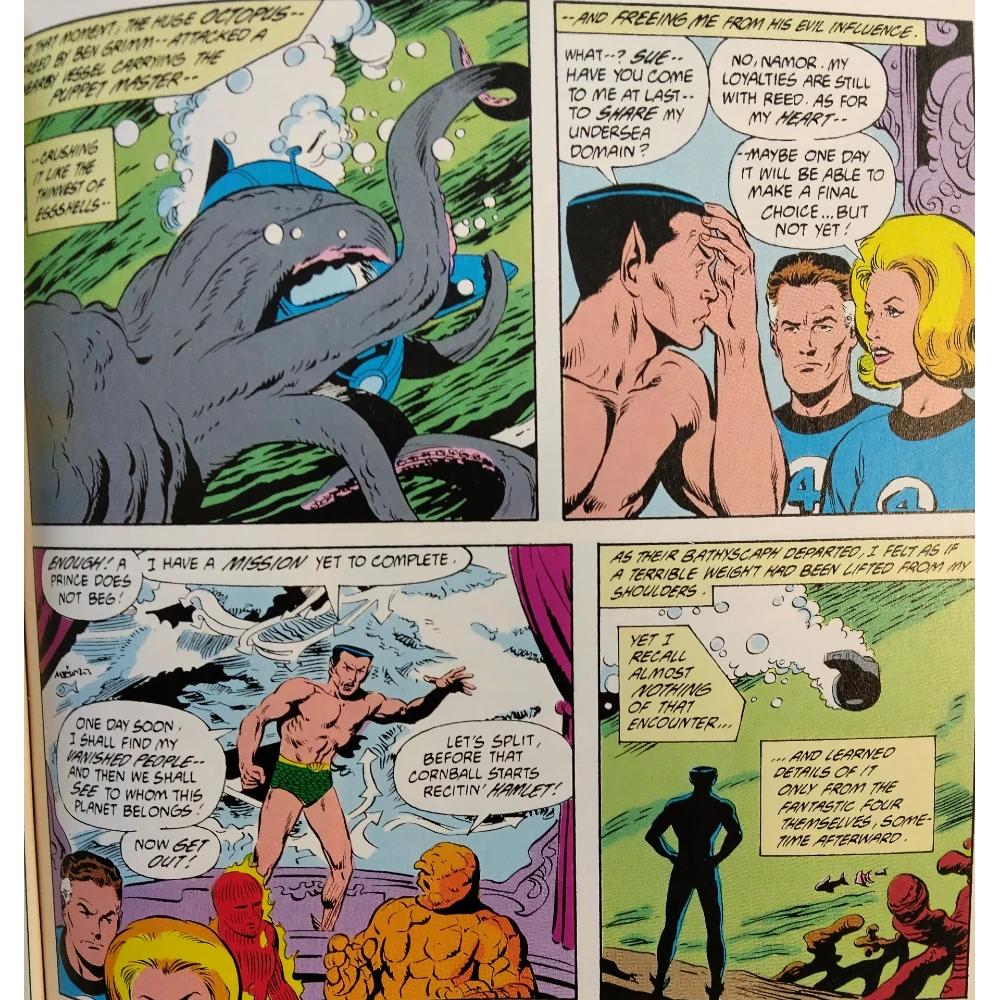

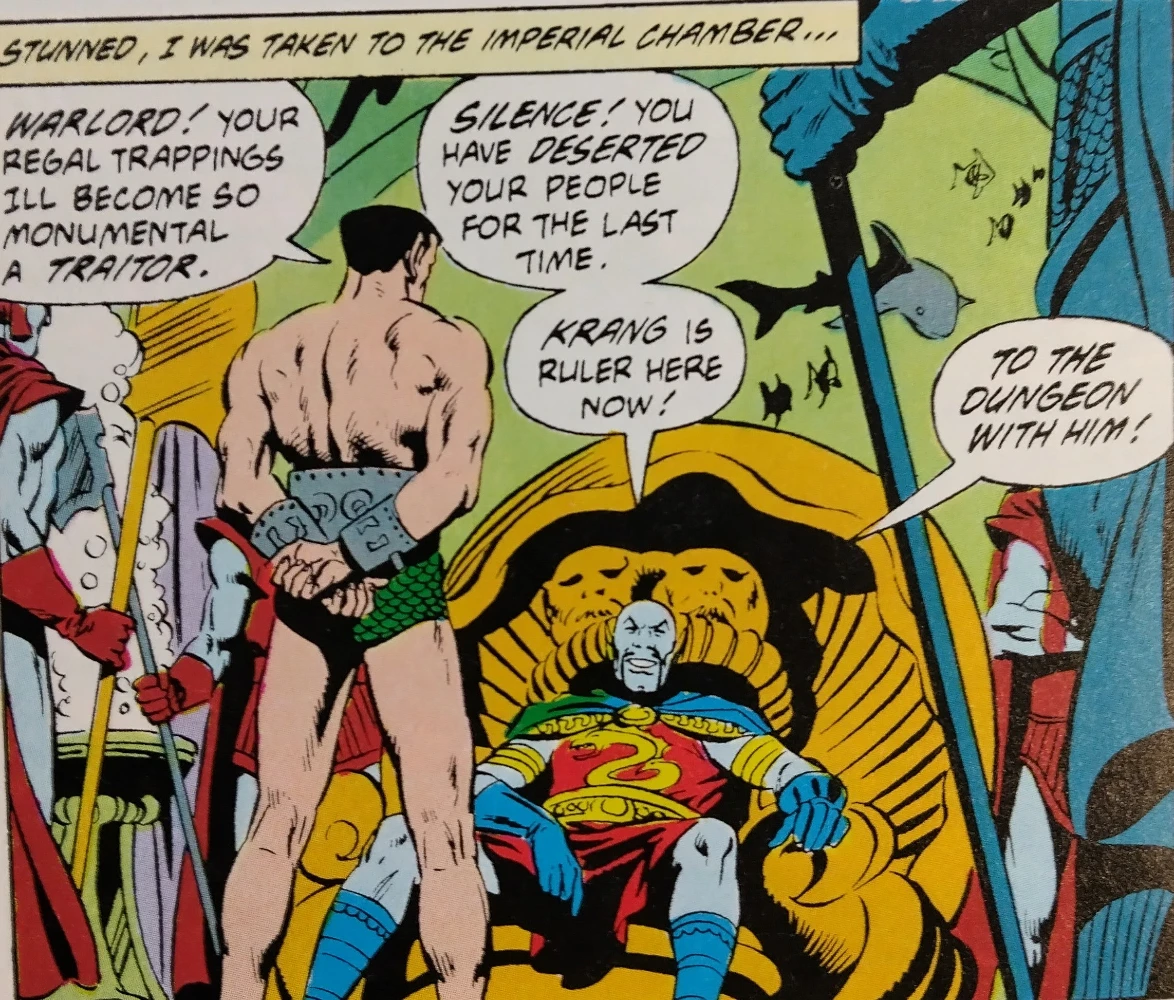

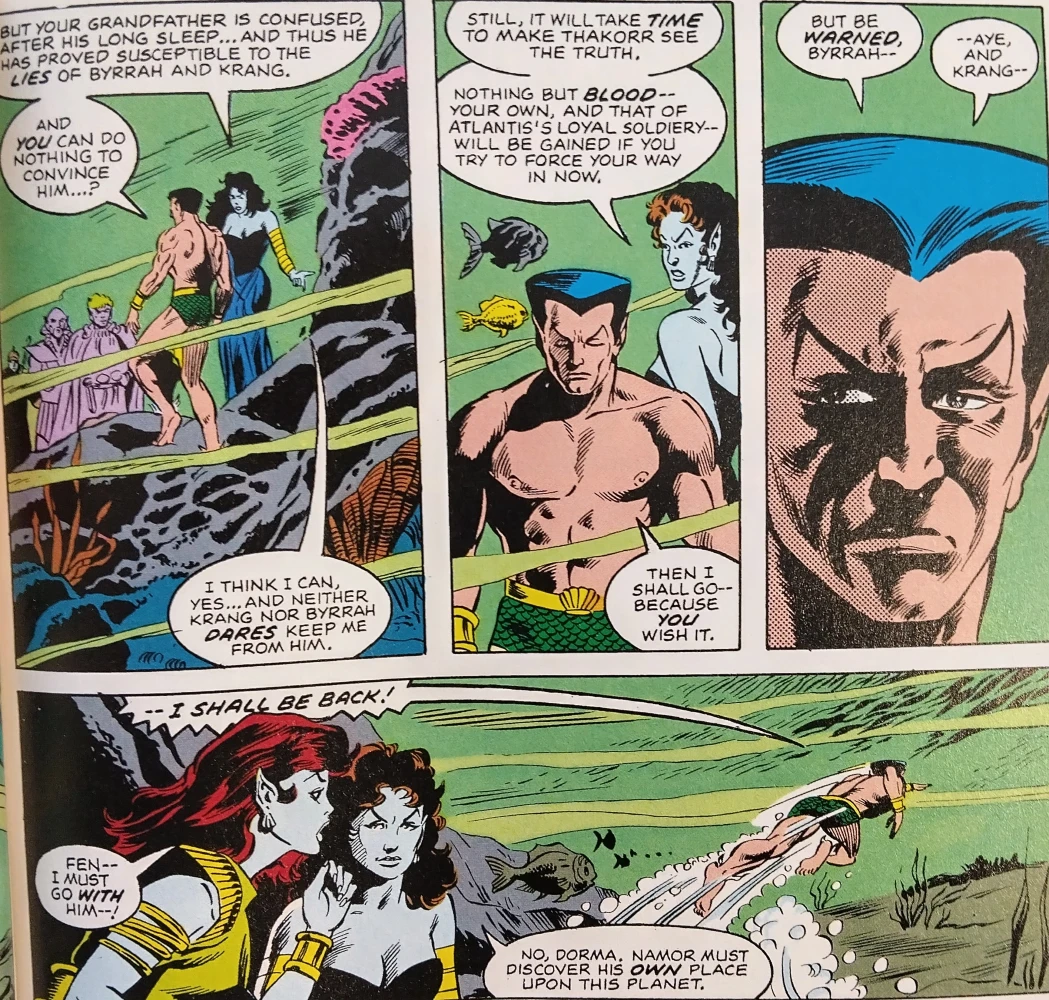

The Thomases find those elements which are consistent across time and emphasize them to the best they can, whether it's Namor's stubborn attitude, his love for Atlantis, his pursuit of women, or his constant internal warring. He, simultaneously, possesses a deep respect for the surface and an irreversible hatred for humanity, at times seeking peace and wishing to be recognized by the United Nations, at other times leading companies of soldiers through the streets of New York. He vacillates between deep faith to Atlantis and a desire for a life outside her walls, at one moment loved by his people, at another despised, rejected, or supplanted by usurpers. This roller coaster provides conflict and insight in specific sections, and it's in these panels where you can tell Roy and Dann Thomas are itching to really sink their claws into the character's personality and make us want to appreciate him all the more. Can't you see the way he thinks and acts? it seems they implore. Look at this constant war he fights! Feel for him and his endless struggle!

And I wanted to, I really did, and in those quieter moments, I found I could, even if only temporarily. The Thomases employ a trick throughout their narrative, told from Namor's perspective as he revisits his history, where he attempts to reconcile his past self with his current mindset, almost apologizing for the way he spoke and acted when he was younger…though he doesn't change all that much across the series. The Namor retelling his tale is working to understand his own behavior, making a silent promise that who he is now is different from who he was. That's only fair: it wouldn't be much of a fiftieth celebration if your hero took delight in the times he killed people, betrayed allies, or acted like a haughty moron.

Unfortunately for the Thomases and Buckler, this history was never intended to be compiled. Namor's story was never meant to unfold organically across the years, at least not for a while after his first several appearances. Issues were told as issues, with little connective tissue in-between. Set aside each other, events which were meant to be read in isolation grate against one another, exposing the repetition utilized in dramatizing Namor's character and the idea that writers across his history seemingly had very little by way of interesting concepts to stick to him like a barnacle on a boat. The prince constantly finds himself at the mercy of writers who have only two or three central ways to use him–as a good king, as a refused king, or as a whiny braggart pining for Susan Storm–and those beats are recycled endlessly. He keeps returning to the same locations, with little development having occurred between visits. Enemies, usually the same ones, rise against him and his rule. Namor leaves Atlantis, returns, leaves again, returns, ad nauseum. Panels which do impart some form of forward momentum often come on suddenly, such as the dramatic return of a supporting character assumed dead, offering a glimmer of propulsion before dragging progress back into the swirling depths of repetition.

Namor isn't the only character immune to forward momentum–were you to chronicle the decades-long history of any character at this stage, you'd find similar faults. You'd see Spidey constantly fighting the same enemies, Daredevil consistently at the mercy of the Kingpin, Batman agonizing over letting the Joker live again, Ben Grimm finding a snatch of hope by becoming human before transforming back into the Thing. It's the nature of the monthly comic book, and though the Thomases strongly endeavor to make each step Namor takes look intentional on the part of the character himself, they cannot escape the grip of history. They try, desperately try, and in moments, they succeed in making me believe a certain notion, idea, or theme could have been intentional. It's easier to trust the closer you get to the then-present of 1988 that writers became more serious in laying out plotlines for particular characters and that whatever repetition existed was done with the full knowledge that it was happening. Namor, for example, finds his love life in constant peril, no matter which woman he falls for, be they human, Atlantean, or something else entirely. The more often it happens, the more you want to believe it's something of a cruel joke played against him, to prevent him from finding the true happiness often denied so many other crimerighters, yet that nagging sense of laziness or a lack of creativity from our assembled writers and artists lingers.

It's easier to forgive those faults with the Torch issues, as this second limited series is only a third of the first series' length, with more time passing between certain developments. Roy Thomas (working alone this time around) can more adequately tell the character's history in a condensed format–I assume, partially, because the character's history was not as fleshed out as Namor's. The series ends with a reference to a comic published in 1969, about twenty years prior to the last reference in Saga of the Sub-Mariner. Actually, Jim Hammond references a story published during John Bryne's West Coast Avengers run, but it's a very brief summation in a single text box to quickly bring us up to the present with little in the way of story in-between...probably because the Torch spends significant chunks of time deactivated between certain later appearances.

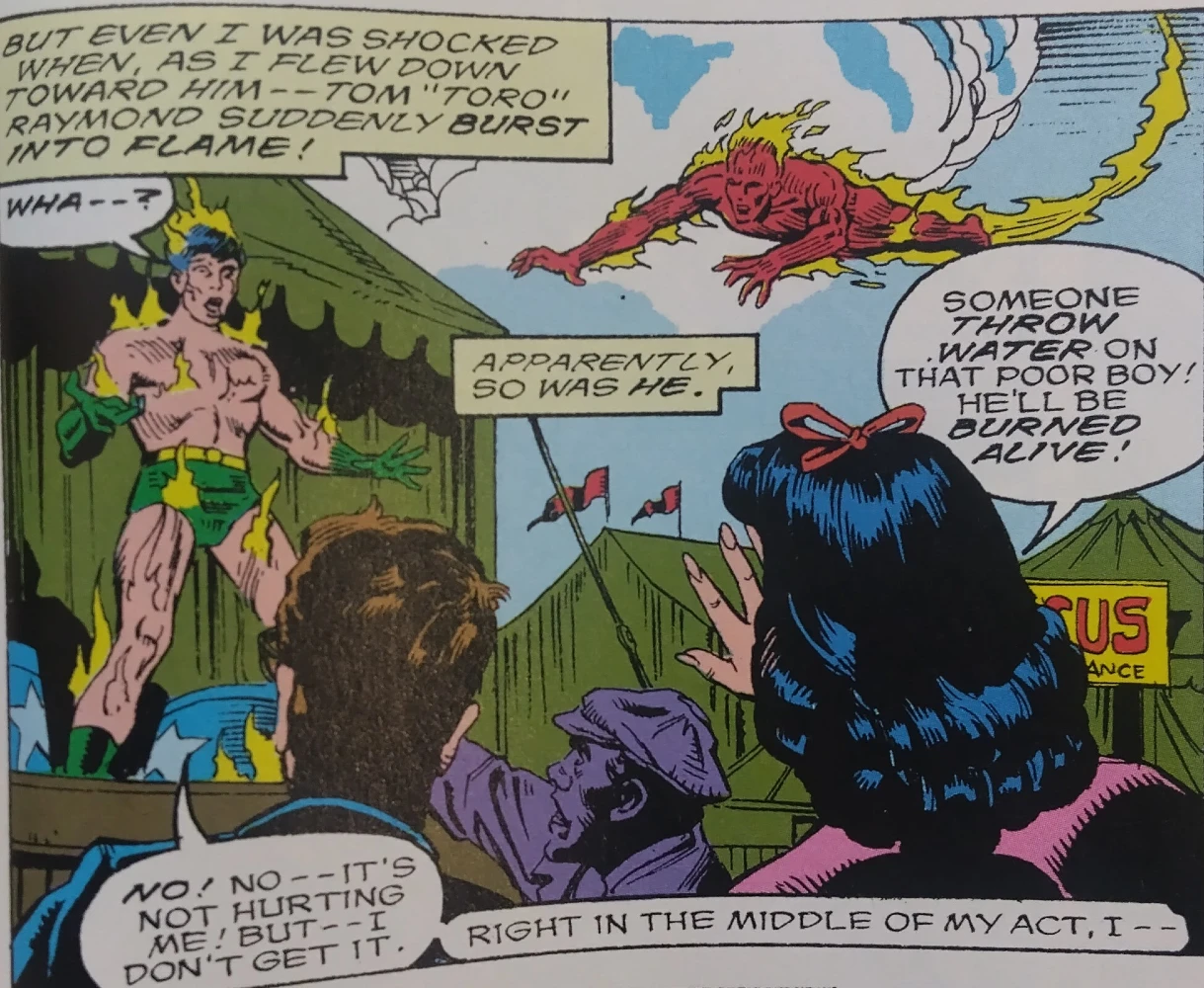

The four-issue structure is more palatable, with a narrative that feels told more organically than Namor's. The repetition is lessened, the characters feel more natural and capable of growth. The series is still a rehash of older comics, but here, the length is more easily justified. There's a lot of goofiness that isn't addressed in any serious manner, such as Jim's sidekick Toro's origin, but seeing these characters take such dramatic developments at face value is part of the charm of the whole thing. As a character, this first Human Torch is a much more noble figure than Namor, less prone to outbursts. Thomas tends to chalk up his personality to Hammond being an android, which is woven in as an interesting and dynamic character trait which may explain some of the Torch's tendencies.

With both of these series, you get the palpable sense that both Thomases are searching for the "story" in "history," taking decades and decades of old, disparate issues featuring the same characters and transforming them into a sensible progression of life events. A is supposed to lead to B, which is supposed to lead to C, and so on. Within the period Thomas covers for the Torch, that notion tends to operate well enough. For Namor, unfortunately, there is such a sheer volume of issues split between two distinct ages of comic publication history that such a synthesis is much more difficult to accomplish. A full story with constant development was never baked into the character's origin, and so the Thomases are seeking a coalescence which never existed.

The idea has merit, particularly for readers like myself who either aren't as interested in those older issues or would be unable to find them. Both the Torch and Namor have decades of history to pull from, and these series allow a look into where they came from and how they developed across the years. Unfortunately for Namor specifically, that history is strewn with repeating locations, characters, and events which were never meant to be justified or explained outside the present moments where they happened. If the Thomases had found a way to perhaps modernize Namor a la Byrne's Man of Steel or George Perez's Wonder Woman, or even if they had chosen to construct new scenes around older ones or introduce new threads, maybe we would've been given a series that felt intentional in developing Namor as a character. Instead, they bow to the whims of writers of old, trapped in the currents of yesterday.