Distinguished Critique: Batman: Gothic Review

Morrison and Janson craft a narrative constructed on opposing ideas, a near seamless addition to Batman's early career

—by Nathan on October 19, 2025—

A while back, I reviewed "Shaman," the first arc in Legends of the Dark Knight, the third ongoing Batman comic series alongside Batman and Detective Comics as a mainstream title. Launched in 1989, Legends intended to capitalize on stories set in Batman's early career, honing in on the mystique which made Frank Miller's "Year One" so popular.

I appreciated how "Shaman" artfully capitalized on that gritty, urban feel which Miller captured in "Year One," giving us a human Batman still trying to find himself in this new world of nighttime vigilantism. Writer Dennis O'Neil saw fit to add some elaboration on Bruce's inspiration for becoming Batman–specifically, why he selected the symbol of the bat–and I'll admit to finding he more successfully wove in the symbolism than he did in developing the plot. It's a fine story that just loses itself near the end.

Grant Morrison was no stranger to Batman specifically and DC in general by time "Gothic" debuted, the writer having developed the Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious House graphic novel with Dave McKean and deep in the throes of an Animal Man run when this arc was published. For those fans of the Arkham graphic novel won over by Morrison's literary sensibilities and symbolism, you'll find material here worthy of that installment. Paired this time with Miller's partner-in-crime on Daredevil and The Dark Knight Returns, Klaus Janson, Morrison weaves a story which both satisfies Legends' "urban crime drama" quota while flirting with more esoteric notions, a fitting blend for the writer.

Batman: Gothic

Writer: Grant Morrison

Penciler: Klaus Janson

Inker: Klaus Janson

Colorist: Steve Buccellato

Letterer: John Costanza

Issues: Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #6-10

Publication Dates: April 1990-August 1990

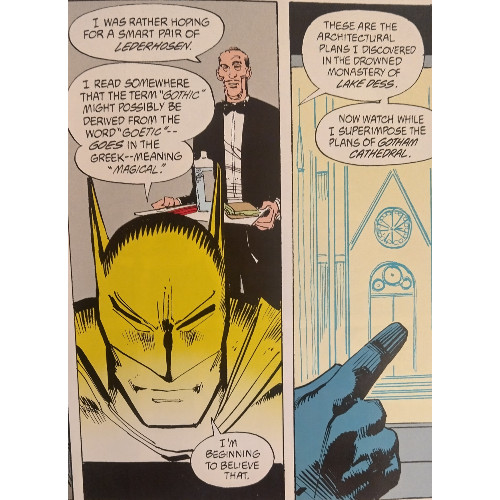

The word "Gothic" finds its roots in "Goth," a term denoting a Germanic people group famed for partaking in the fall of the Roman Empire; a bit of research indicates some Renaissance scholars used the term "Gothic" in reference to architectural forms they felt clashed with the prevailing themes of the era. Gothic buildings, with all their points and arches, were ugly when compared to the beautiful Roman contributions to architecture, such as stately marble columns. As the Goths opposed the progress of the Roman Empire, so too did the hideous, barbaric points and arches clash with the progressive columns and other classical contributions to the art form. Art and architecture being subjective as they are, the term appears less pejorative these days than when it originated.

Such an architectural form dominates Gotham–there's that root word there again–a city itself often associated with the ugliness of crime and corruption. There's a hideousness to the city's underbelly that seeks to poison the entire scope of Gotham, and it's this ugliness from which Morrison derives the plot. The narrative itself deals principally with the reopening of a gothic cathedral, but this is Grant Morrison we're talking about, and I have no doubt the writer fully intended the title to have more than one meaning.

"Gothic" is a very purposeful narrative, in that you can tell Morrison thought through at least most of the plot prior to penning a single issue (a notion that feels true even if you weren't aware of the author's proposal, included in the back of the trade I own). Hints introduced earlier are followed up by the final issue, a seemingly innocuous supporting character returns in a very dramatic moment near the end (upstaging this reader's own personal "fan theory" during my first readthrough), and even the cathedral, obviously indicated as important from the beginning, fulfills its purpose in a satisfying manner. Even though you can notice Morrison's hints, our Batman still must unravel the mystery himself, and though the inclusion of the cathedral as integral to the plot may not be a surprising twist, Morrison does well to include it to at least capitalize on earlier seeds sown.

There is a lot to unpack here, and Morrison, as the writer often does, is not going to allow the audience an easy time in picking apart all the references and nods. I began my second reading with a greater intention to pay attention to Morrison's allusions, but I soon lost interest, not wanting to Google a name or quote or title of an opera every five pages. It can get dense and may alienate some readers. At moments, I do feel Morrison sacrifices straightforward storytelling for opportunities to sound incredibly smart or clever, but I feel fairly used to this when reading a Morrison comic. There will always be material I just don't fully grasp and can't quite fit into the narrative being told.

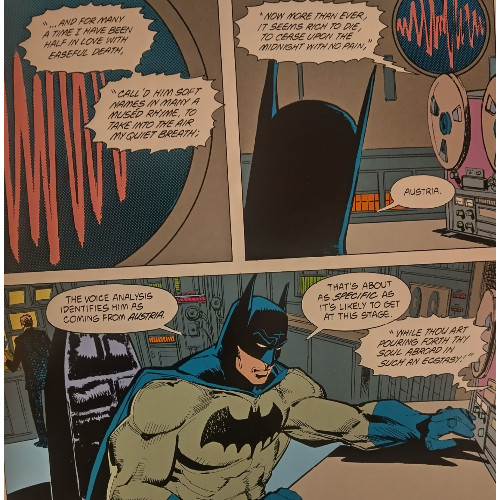

What works for Morrison and artist Klaus Janson much better is their ability to provide balance between seeming opposites. Where scholars may have believed gothic architecture clashed with classical, Morrison and Janson capably weave in conflicting ideas well. The main plot showcases this in pitting Batman against a seemingly immortal enemy, drawing the grounded vigilante into trouble with the supernatural. Morrison and Janson's introduction of villain "Mr. Whisper" is appropriately eerie, casting him as a serial killer who may have just existed for hundreds of years. In a similar move to Jim Starlin's Batman: The Cult, published a year earlier, the duo toy with the audience, making you wonder the truth behind Whisper. The man, whom Batman recognizes as a former, brutal headmaster at a boarding school he attended briefly as a child, looks not a day older than he did twenty years ago…and like the Russian mystic Rasputin, seems to have returned from a very definitive demise. What is the truth here? What can we believe? Morrison provides the answer, and it may not be the one fans initially expect him to uncover; though it steers the comic towards the outlandish, it works nevertheless.

Tonally, Morrison and Janson weave the fantastic alongside the human, endeavoring to incorporate just enough doubt to make the reader wary until the end. I often prefer my Batman stories to be completely grounded–I love The Dark Knight, in part, because Christopher Nolan makes you believe a terrorist could slather on makeup like a clown and bring a city to its knees. "Year One" gorgeously argues for the practicality of an urban vigilante like Batman, and even The Dark Knight Returns paints a somewhat realistic portrait of an aged Batman (aside from the weird, flying baby bombs). Similarly, Morrison convinces me that Batman is right at home with the eerie Mr. Whisper waltzing about. A seemingly unkillable killer, evidence for ghosts, and other legends add to the narrative rather than take away from the groundedness.

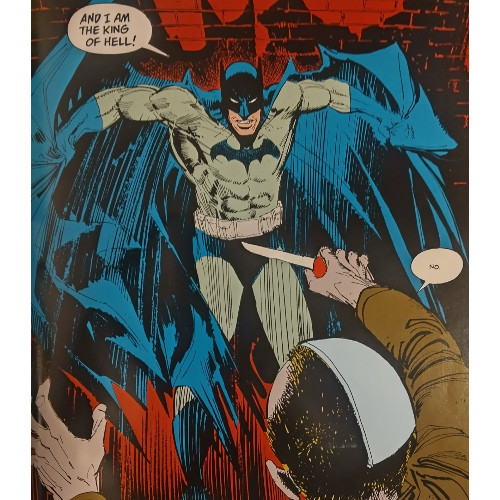

This works as well as it does principally because Batman himself provides the mortal tether needed to keep us fixed to reality. We are early in his career, in a time where he's still defining himself and what he means to the city and its inhabitants, and he provides theatrics to help cement his position as something more than human. "I am the king of hell!" he snarls at a few muggers, terrifying them. He refuses to work with mobsters seeking his help, incapacitates a thug while his oblivious boss is standing in the same room, and is often illustrated by Janson giving the most unsettling grins. He's one of the good guys, but he's a demon in bat's clothing to the Gotham underworld, and Morrison and Janson know just the right moments to have him scare the daylights out of these criminals.

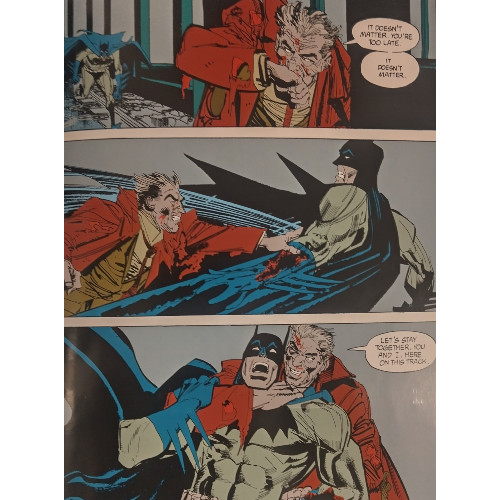

And yet…he is still very human. It's that balancing act again, this time applied to our Dark Knight Detective. Some of the arc's best moments see Bruce at his most vulnerable, whether it's him being pushed off a roof edge by an enemy or resting his back against a wall and then collapsing after a harrowing, last-minute save. He puts on a brave face–"Bring a band-aid," he tells Alfred when requesting a pick-up–but there are necessary wounds inflicted on him to remind readers how much like us Batman is.

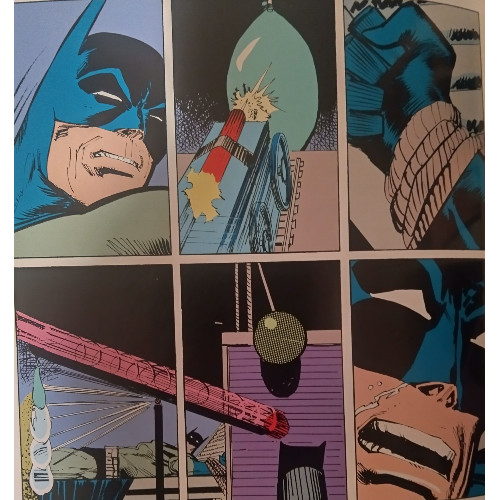

I do want to touch on the arc's most perplexing moment: a scene where Bruce is tied to an elaborate deathtrap–itself an amusing juxtaposition against the arc's grittier use of violence–sees Batman escape…somehow? It's not shown very clearly, and even in Morrison's proposal, the writer merely notes that "He escapes." I was initially confused by the scene and ruffled by its ambiguity, but given that so much else feels intentional and how Morrison notes it in the proposal, I feel this has to be intentional. I'm still left somewhat confused as to why Morrison directed the scene this way, as I don't believe it was Morrison's inability to allow Batman a clever, successful escape. My rule of thumb with good deathtraps is that the writer must inherently devise a means for the hero to escape that doesn't hinge on coincidence, and this one doesn't even hinge on happenstance! It just…happens? I want to say it's Morrison giving in to the mystique of Batman as this incredible detective/escape artist, that, of course, Batman would escape! Why wouldn't he? He's Batman! It's a hint of the absurd coming to the rescue, a moment where Morrison's otherwise grounded vigilante indulges in some silliness.

As other writers before, Morrison endeavors to tie in some of Bruce's past, not necessarily to retcon events, but to allow more credence to certain notions. In this case, Thomas Wayne removes Bruce from an abusive private school and decides, as a celebration, to see a movie at a local theater. Whomp whomp. We see this kinda stuff all the time in comics, where it just so happens that an important event is suddenly connected to or given close proximity to this story over here or that story over there. It's a little more cheesy than clever. In fact, despite its importance to the plot, I found myself uninterested in "schoolboy Bruce Wayne." One fairly significant, traumatizing experience is recounted for the plot, but Bruce brushes over the psychological implications like they don't matter at all. They explain, perhaps, a brief moment of fright Batman experiences late in the story, but otherwise, he discusses it far more innocuously than I would imagine.

Like with "Shaman," I have some scruples with Morrison's Legends contribution. I'll credit both Morrison and Janson for acing the "tell a Batman story early in his career and maybe dig a bit into his humanity" assignment, and they do a fairly good job at creating a tale different from "Shaman." Similarities exist–our Batman is young, vulnerable, not yet a legend even if he can inexplicably escape deathtraps and encounters some spooky supernatural vibes–and Morrison, more so than O'Neil, has considered the entirety of the plot. "Gothic," like the stones men used to construct those cathedrals, can be a tad too dense at times, whereas a few plot points don't land with the weight they should. Elsewhere, Morrison is like those cathedral spires stabbing at the heavens–pointed, direct, unafraid to take a few jabs to see exactly how our Batman bleeds.