Distinguished Critique: Catwoman: Her Sister's Keeper Review

This limited series constructs an entertaining follow-up to "Batman: Year One," even if some of the pacing is muddled and characters a tad flat

—by Nathan on May 28, 2025—

In 1987, when Frank Miller modernized (for the late 80s) the concept of Batman, he also modernized the concept of Selina Kyle. A woman of dubious background and career options, Selina played a not insignificant role in "Year One," going toe-to-toe with a disguised Bruce Wayne before showing up later as Catwoman to save Batman from Carmine Falcone (fans of the Robert Pattinson movie will remember the part where she scars Carmine's face, though I'd argue his injuries are more apparent in "Year One" and its "follow-up" The Long Halloween). Miller's focus was Batman, but he created a Catwoman who aligned with the gritty, grounded Gotham surrounding this gritty, grounded Dark Knight Detective.

But what if I told you that wasn't the end of Selina Kyle's story…or even the true beginning?

In 1989, someone at DC decided to expand upon the character as Miller introduced her. Writer Mindy Newell was tasked with writing a four-issue limited series reintroducing us to the feline-themed burglar, to draw us into the soul and mind of the woman whose best act of thievery has always been stealing Batman's heart.

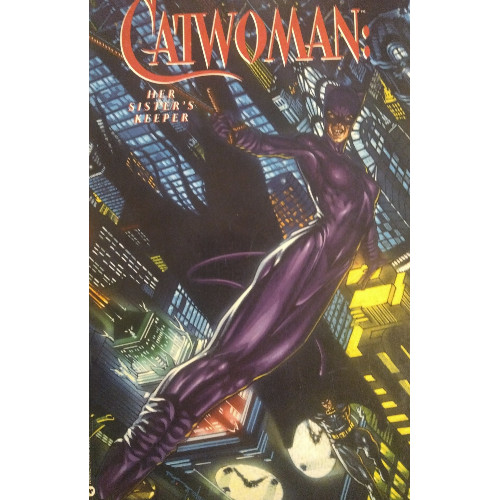

Catwoman: Her Sister's Keeper

Writer: Mindy Newell

Penciler: J.J. Birch

Inker: Michael Bair

Colorist: Agustin Mas

Letterer: Adrienne Roy

Issues: Catwoman #1-4

Publication Dates: February 1989-May 1989

In the biblical book of Genesis, God comes to Cain, the son of Adam and Eve, after Cain has killed his brother Abel. When God asks Cain where Abel is (knowing full well the answer, of course), Cain feigns ignorance. He doesn't know, he says. "Am I my brother's keeper?" he asks God. The question has, in the popular conscience, extended beyond its initial use by the world's first committer of fratricide. It's a question which wonders how much we are actually responsible for those around us, and not just our biological siblings. In the case of this four-issue limited series, the question does center on biological sisters…and, if interpreted a certain way, maybe means more.

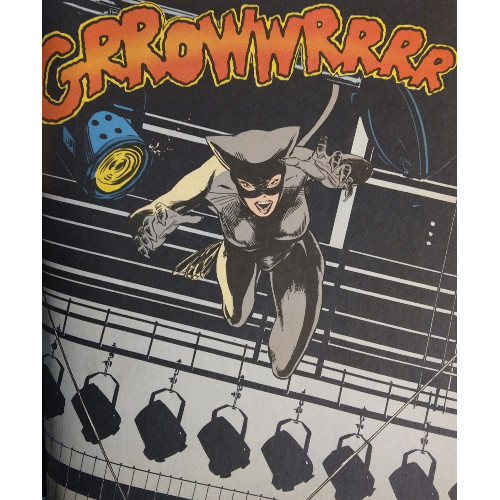

What initially intrigued me about this series was its direct relation to the events of Miller's "Year One," with one or two scenes in the first issue lifted almost directly word-for-word from Miller's script and with J.J. Birch doing his darndest David Mazzuchelli impression (and not just in these early scenes but throughout the book). Miller gave us glimpses of Catwoman, from her little spat with Bruce Wayne, her agility foreshadowing her later feline persona, as well as the inspiration she takes from Batman when donning a costume later on in the narrative. I wanted a story which gave us more development on Catwoman's end, spoke to her motivations beyond "Yeah, I should wear a costume too."

In this, Mindy Newell succeeds. That isn't meant to come across as trite as it possibly sounds. This is Newell's intention with the series, and by time it wraps up, Selina Kyle and her alter ego are allowed that much-needed development. The boxes are checked, the tale is told. We can pluck the cat hairs off our jumpsuits and head home for the evening…or early morning, I guess, because those vigilantes stay out late.

If the above sounds somewhat disparaging or reaching to find praise, it's because I do have obvious issues with the series, and they are the first bits which come to mind. But I'd rather focus on the positives than the negatives immediately, so let's begin with where "Her Sister's Keeper" fulfills its promise.

We are given a well-rounded Catwoman, a character who seeks to break away from the life she's lived in the manner she wishes to, inspired by another costumed vigilante. Newell makes no bones about the fact Selina is someone of questionable morality; she doesn't try to celebrate her past decisions in a "I had no choice" manner, nor does she excuse Selina's current activities as a thief. Selina recognizes, in both instances, she's prowling along the wrong side of the law, and she recognizes she's made such a choice with both activities. Is it something most readers would agree with? No, probably not, but there is a, dare I say it, level-headed approach to determining her path forward, consequences or not, right or not. The intentions won't necessarily persuade the reader to agree, but Newell forgoes any cheap attempts at emotional manipulation. There is no "Will Selina become Catwoman or won't she?" trickery moving ahead. There's not even a "steal from the rich to help the good" aspect here. There is some talk about the kind of Catwoman she may be, but it's fairly clear from the start we're not reading about a superhero or even a do-gooder vigilante. Selina is tarnished, and tarnished she will remain.

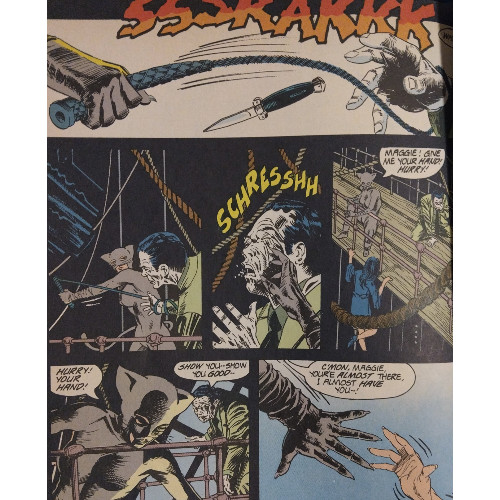

Religion, Catholicism in particular, plays an important part in the narrative, and it's here where some complexity is introduced into Selina's more straightforward approach to her lifestyle choices. I don't know if Newell is the first person to inject religion into Selina's story, similar to how Frank Miller introduced Catholicism to Matt Murdock's devilish defender of Hell's Kitchen, but the notion is played well. Catwoman's (biological) sister is a (religious) Sister, a nun, putting her at theological odds with her sibling once she learns Selina is a costumed thief. Sects of Christianity, I've found, aren't often treated respectfully in comics, or just seem to be misunderstood, but Newell handles the situation without coming across as disparaging. Selina's sister's feelings are well-intentioned and treated as such, offering a juxtaposition to Selina's own confidence. Both walk a path they believe is right…how are you, dear reader, supposed to react to that?

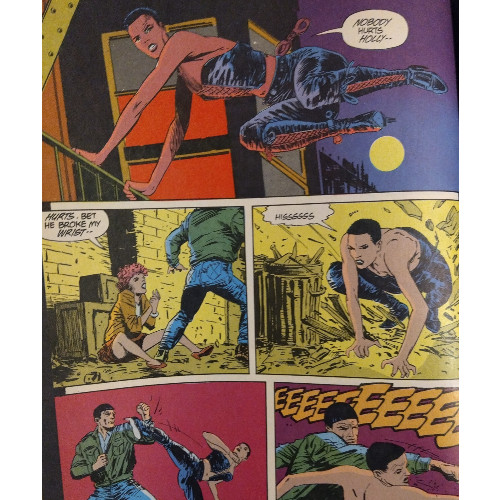

Thus, we also see the volume's title, "Her Sister's Keeper," come into play. Who keeps who? Is the nun responsible for the actions of her cat-thief of a sibling? Does Selina owe it to her sister to walk a straighter line? And what of Holly, a slightly younger girl exposed to the lifestyle Selina lives? Selina is protective of her to the point of placing herself in the way of physical harm to keep Holly safe. But can she really say he's a good role model, mentor, or guardian for Holly, with what we know of her past? Heck, Holly seems to have the most common sense out of anyone in the story, urging Selina to maybe not go galavanting across the rooftops of Gotham dressed as a cat. She's thrust into the role Selina is supposed to show her, Selina choosing the fantasy instead.

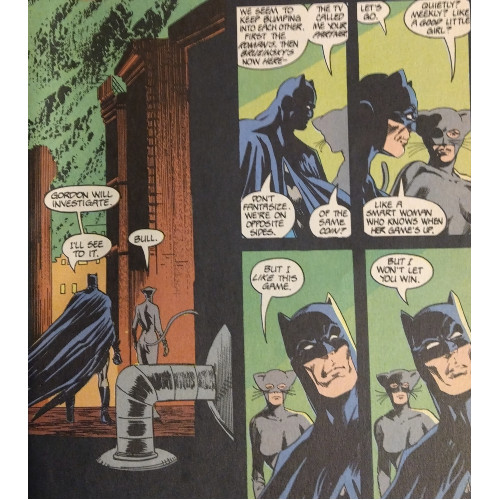

Other relationships in the series–such as those involving an albino thug, a detective, and the Dark Knight himself–feel secondary to the triumvirate of "sisters" weaving themselves throughout the narrative. These supporting characters are necessary to drive tension and conflict–it's the detective who seems to force Selina's hand in some aspects, and it's the thug who largely inspires her to don the cat costume in the first place (he's the one who gives her an early version of the outfit, actually). They just don't feel as interesting beyond that necessity; we need a bad guy to hate, so the bad guy's there, and this kind of story welcomes the grizzled police detective who's empathetic towards our hero while suspicious of her because he supports the law foremost. Batman's inclusion was the most concerning, as I was worried he'd feel forced into the narrative simply because he's Gotham protector and because of his history with the protagonist. The vigilante plays a role, certainly, and his introduction as Bruce Wayne in the Miller-mirrored scenes feels appropriate. He doesn't steal attention, nor does he add much of anything other than performing a last minute save which feels equal parts unavoidable and unnecessary. He's just there, I guess? Not too integral but not just a shadow in the background. If anything, Newell doesn't allow him, until that save, to cheapen Selina's integrity as a quasi-protagonist.

What's more problematic is Newell's pacing. This is a series that could have easily included an additional issue, maybe two, and not felt unnecessarily padded. The first issue moves like lightning between scenes, directly jumping from one action to the next and lacking much rhythm. Not that transitions are always necessary, but the writer who can use clever dialogue or an artist who can echo an image can allow scenes to flow together without the switch feeling jarring. The changes here are rough and abrupt, often across time as well as space, and causing missing moments. A cop car screeching in front of Selina after she tussles with Bruce at the end of one page is continued with a panel of Selina approaching boxer Ted Grant (aka, Wildcat) for a self-defense lesson, with nary an indication of what happened in-between. The pacing improves as the series continues, but I found myself flipping between pages early on, trying to determine if I missed anything or if my copy was missing pages.

I won't label this limited series among my favorite post-Crisis reconstructions of classic DC characters. Newell does interesting things with Selina's character, largely adding to the foundation Miller laid in "Year One," so it's mainly a matter of comparison. I've reviewed some absolute classic reintroductions to DC's heroes–like "Year One," Man of Steel, and The Longbow Hunters–and enjoyed a few hidden gems, such as Tim Truman's Hawkworld. "Her Sister's Keeper" can't quite stand shoulder-to-shoulder with those bastions of narrative. Newell understands her assignment and works admirably to construct a clever character around the pieces provided. As I noted, there's no waffling with this Catwoman–she's true to who she's supposed to be. The characters around Selina are kind of flat, pressed into service because they align with common character tropes. Even Batman feels included out of necessity. And the pacing can be tricky, making for a confusing first reading experience. But maybe a few problems won't kill the cat who's curious about Ms. Kyle's capers, especially if you have eight lives to spare.