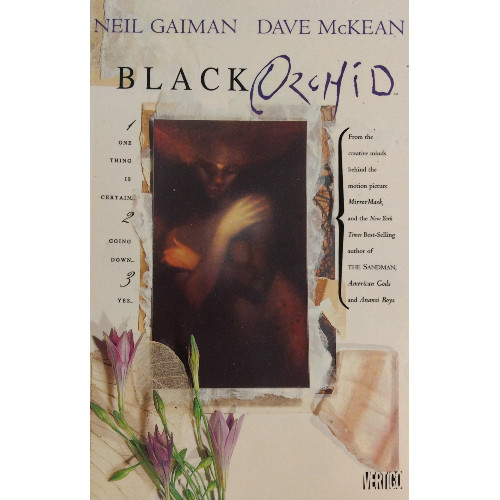

Random Reviews: Black Orchid

A well-crafted debut from an iconic storyteller applies earnestness and wonderfully atmospheric art to a virtually unknown character

—by Nathan on November 13, 2025—

These days, if they're able to look beyond the recent allegations levied against him, comic fans are likely most familiar with writer Neil Gaiman for his work on The Sandman or the graphic adaptations of several of his novels (I personally first encountered his work in the Eternals series he wrote for Marvel alongside John Romita Jr.). Sandman, however, wasn't how he broke into American comics. No, Gaiman got his start at DC with this limited series, Black Orchid. Much like Sandman, Black Orchid represents a modernization of an older character, in the same vein of other 80s series such as Green Arrow and The Question. Research indicates Gaiman, along with artist Dave McKean, had actually wanted to work with several other characters, including Green Arrow and John Constantine, but because of Mike Grell's Longbow Hunters and Jamie Delano's Hellblazer, one of Gaiman and McKean's desired characters lower on the list was selected.

I know virtually nothing about Black Orchid as a character, other than her brief appearances in John Ostrander's Suicide Squad. But given I've been working through some material which was later collected under DC's Vertigo banner, I wanted to give Gaiman's first American comic a try. As I noted, this is a renewal of a character who originally appeared in 1973, similar to how Grant Morrison renewed Animal Man or Alan Moore revitalized Swamp Thing. It's also a proper origin for the Black Orchid, her lack of which seemingly a running gag prior to Gaiman's series.

Which I guess is only appropriate. We are dealing with a character who is a human/plant hybrid, so why shouldn't we learn which seeds were planted and led to her growth?

Black Orchid

Writer: Neil Gaiman

Penciler: Dave McKean

Inker: Dave McKean

Colorist: Dave McKean

Letterer: Todd Klein

Issues: Black Orchid #1-3

Volume Publication Date: September 1991

Issue Publication Dates: December 1988-February 1989

Publisher: Vertigo (DC Comics Imprint)

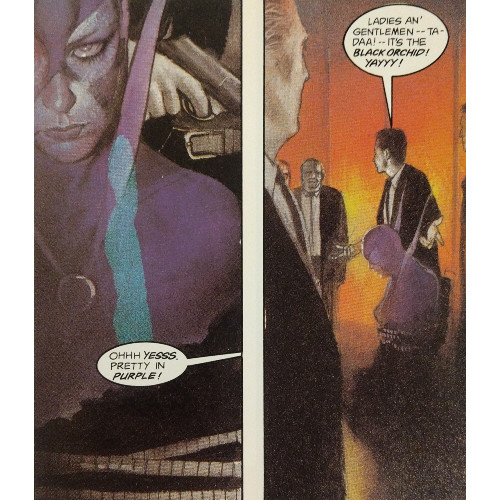

Susan Linden has led a rough life. If getting killed by her criminal husband and resurrected to fight crime as the Black Orchid wasn't a difficult enough situation, she's killed a second time within the first few pages of this series–shot in the head, set on fire, and then blown up, for good measure. I guess the guy must've heard about the whole "resurrected after getting killed by her criminal husband" thing, which would make sense, because this second dude and her (now ex-)husband work for the same boss, a multi-million dollar businessman you might've heard of named Lex Luthor. Susan may just be in the wrong line of work.

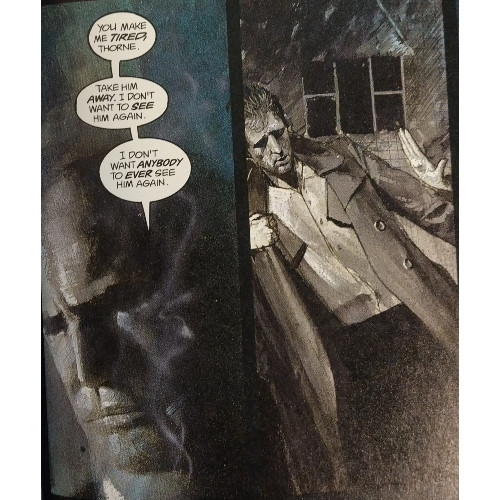

I joke, but the trials Susan undergoes, followed by a second resurrection as this new incarnation of the Black Orchid, underscore the brutality and reality permeating this series. That word "reality" should find its way into your nostrils like a sweet rose as you head into this series, because a good groundedness exists here…yeah, in writing a series about a plant woman, Gaiman creates a solid world, one where the darkness of existence haunts every corner and where very human emotions pour throughout the pages. We never see an abusive father strike his child, but we feel the grip of his hatred over his young daughter; a husband stalks his wife, his bitterness coursing through each word and action; Luthor and his people can get away with murdering scientists, bribing firefighters, funding South American expeditions and hiring mercenaries. No aliens come to conquer or demon lords declare hell on earth. Very real men perform very real actions with very real consequences…and those consequences are felt palpably.

The darkness and violence is intended to lead us to develop empathy for Susan in her newest form, as well as a younger Black Orchid who follows her. Theirs is a mission of identity, caught up in this new existence, and as they look for answers as to who and why they are, they brush up against the unfairness of the world. They don't fight back, not really–there are none of your standard superhero dust-ups here. These Black Orchids seek other solutions outside the violence inflicted against them, but Gaiman layers on the pain to discourage and frustrate them. Dead friends, dead ends, armed stalkers…if Susan is seeking a rebirth and a new purpose, she is confronted at every turn by people who want to nonchalantly drag her back into the darkness of how they do things.

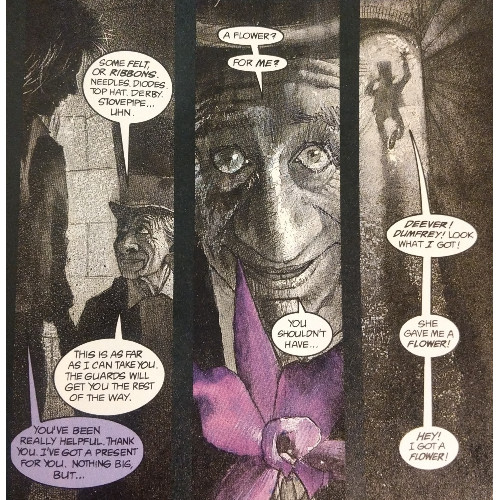

Gaiman's writing is incredibly fresh, and I want to chalk that up to him having established himself as a writer outside of comics and then coming into the genre, similar to a Kevin Smith or Jeph Loeb. As an outsider, Gaiman by this point had developed a knack for developing dialogue which still feels, much like his story and at the risk of sounding repetitive, real. Characters cut each other off, curse, quote lyrics, repeat themselves, speak in broken sentences. The perfect, polished cadence of typical comic book parlance is thrown out the window. People speak naturally here, in ways which don't always propel the story forward but which help give insight into who they are as characters.

If a complaint can be found anywhere, it's in the ending–a tense sequence building to the tale's culminating moments feels abruptly shortened, a resolution found a bit too quickly for my tastes. There is a way which this resolution tethers into those ideas I mentioned earlier, of our Black Orchids seeking a solution outside of violence, of them representing a "better" method of working than slipping into the murderous intentions of characters like Luthor and his men or even Susan's ex-husband. But the turn around which this theme moves is abrupt, a minor character's coincidental change of heart having a larger impact than it should.

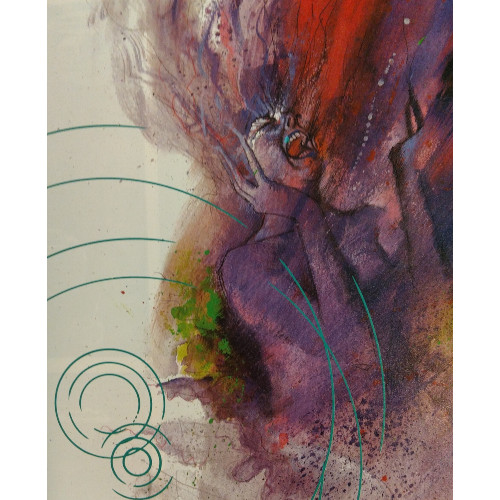

No complaints to find, fortunately, regarding Dave McKean's artwork. The year after this series was published, McKean worked with Grant Morrison on Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, and a sequence in Black Orchid's second issue where Susan visits the infamous asylum feels like a trial run of McKean's work there. As in the graphic novel, McKean is interested in creating a powerful atmosphere–his characters here are more defined than in Morrison's graphic novel, which only lends strength to the grounded feel Gaiman provides. Arkham feels more like a dream, or perhaps a nightmare, with settings and characters cloaked in necessary shadows. Here, darkness does linger, but form feels more important.

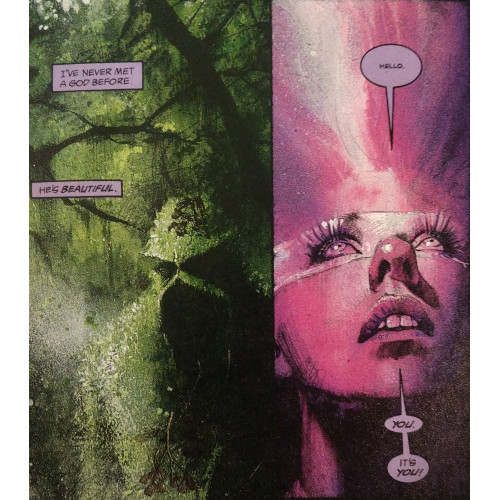

McKean's colors are wisely used, sparingly at moments when they should be then spread prodigiously where appropriate. Hues of grays and blacks cover much of the world he creates, Susan's startling purple providing a stark contrast when he is reborn in her Black Orchid form–even before, actually, prior to her second death, a striking purple figure against the backdrop of an office boardroom. A sequence where she meets Swamp Thing offers a flurry of two colors, greens and purples meeting in a seamless manner where the contrasts work together rather than combat each other, much as they do in supervillain costumes, like those of the Green Goblin or Mysterio. Without Susan, the world, and often people, feel intentionally drab, devoid of life as they are devoid of peace. As she offers a new way to move through life, so does Susan give a splash of color against the gray backdrops and gray people winding their way through existence.

Links to the wider DC Universe, such as the Swamp Thing meeting, enable Gaiman to toy with a few concepts. He develops former friendships between Susan, Alec Holland (Swamp Thing), Pamela Isely (Poison Ivy), and Jason Woodrue (the Flouronic Man, a Swamp Thing enemy), creating a connection between people who would develop powers associated with vegetation. Gaiman uses one character to create bitter situational ironies–a shame Alec was killed in that explosion, right?–but any reader with a grasp of DC history will catch the fun references. Gaiman doesn't spend a lot of time linking these characters to each other, but even the idea that a connection exists gets the reels of my imagination rolling. It's fun to think of these characters inhabiting the same space at one time, and the idea was actually what generated my interest in Black Orchid to begin with. These connections do have story elements which are drawn from them, but the geek in me appreciates them even as references.

In the series' opening scene, a captured Susan is taunted by a cruel businessman, who tells her, "I've read the comics. So you know what I'm not gonna do? I'm not going to lock you up in the basement before interrogating you. I'm not going to set up some kind of complicated laser beam deathtrap, then leave you alone to escape. That stuff is so dumb. But you know what I am going to do. I'm going to kill you. Now." And then he has a henchman shoot her in the head. I don't fully agree with the idea of laser beam deathtraps being dumb–I like that Silver Age kookiness in moderation–but from a criminal businessperson standpoint, yeah, I can see where he'd skip all that. Subtly, it also feels like commentary from Gaiman: we're skipping the dumb stuff, the kid stuff. This comic is for intellectual adults. It has substance, purpose.

For Gaiman's first American work, Black Orchid is a strong debut, a character-focused narrative driven by plot rather than cliches. It's a very different comic than what the average reader will encounter, even if it hinges on several DC Comics characters. The intentionality behind Gaiman's script, the efforts by McKean to create a strong atmosphere, the necessity of creating something fiercely grounded rather than something cosmic or crazy...all of it allows the series to sprout from a well-seeded earth in full, colorful bloom.