Spider-view: Avengers: Deathtrap: The Vault (Venom, Part 4)

Though not extraordinary, this graphic novel presents some engaging character moments in its study of captive criminals

—by Nathan on April 27, 2023—

The Vault.

It’s all in the name, isn’t it?

You hear “Vault,” you think someplace secure, safe. Where valuables are stored, under lock and key. Maybe armed guards patrolling.

Of Marvel’s superhuman prisons, it certainly sounds the most imposing. Not that it has great competition. I mean, sure, the genius who looked at a squarish-shaped prison and called it “The Cube” probably didn’t see the humor in naming a prison where villains are shrunk to Ant-Man-size “The Big House” or a S.H.I.E.L.D.-run facility situated on an island called “The Raft.” Those last two are kinda funny…but “The Vault”? It’s no (creepy laughter increases) “ARKHAM ASYLUM” (thunder cascades in the background!), but it strikes a certain pragmatic chord. Again, that sense of security. It’s a big vault. You close the door, spin the lock, hear it click in place, slap the dust off your hands and walk off whistling a cheery tune, knowing your darkest nightmares are stored safely within…

…or are they?

(more thunder)

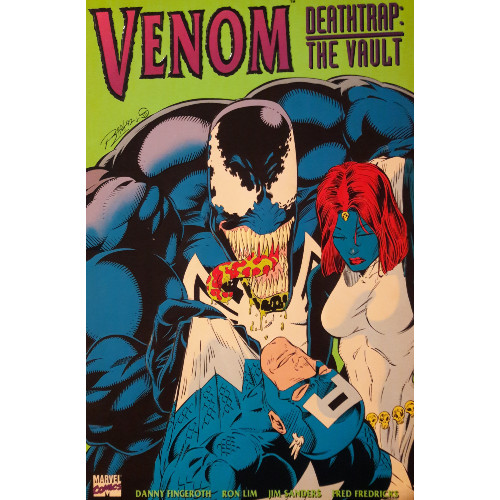

Avengers: Deathtrap: The Vault

Writer: Danny Fingeroth

Penciler: Ron Lim

Inkers: Jim Sanders, Fred Fredericks

Colorist: Joe Rosas

Letterer: Joe Rosen

Issue: Marvel Graphic Novel #68

Publication Date: September 1991

A brief note, before we move on: my copy has been relabeled “Venom: Deathtrap: The Vault,” for reasons unknown, but as the original publication was titled with “Avengers,” I’ve kept that distinction here, even though my cover sports the different title and though I've included it in my "Venom" series of posts. Thanks for the interruption. Just wanted to clear up any confusion.

I’ve noted, previously, the roller coaster quality of Marvel’s original line of graphic novels. On the higher end, you get memorable fare such as Jim Starlin’s The Death of Captain Marvel and Chris Claremont’s God Loves, Man Kills. In the more “middling” range are narratives such as Cloak and Dagger’s appearances in Predator and Prey and Shelter from the Storm. These graphic novels (or, at least, the ones I’ve reviewed) tend to at least try something bold: killing off the character Jim Starlin turned into a cosmic champion, allowing Bernie Wrightson to try his hand at a crazy Spidey fantasy story, covering Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson’s whole history, or turning the mutant/humanity conflict into quasi-religious allegory. The results tend to work more favorably when writers can concoct original stories that positively affect continuity. These tales should feel special, unique, worthy of the “graphic novel” label.

Deathtrap pulls with all its might but can’t quite get its chin over the bar.

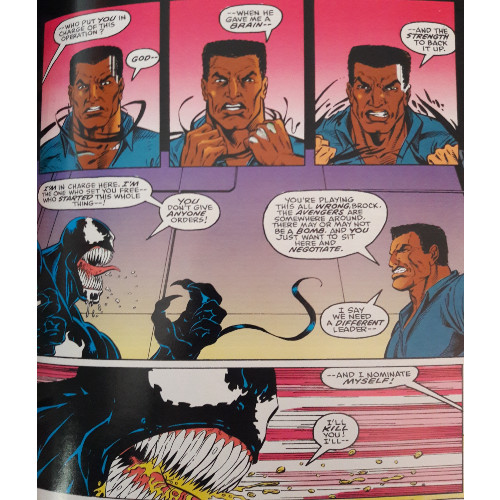

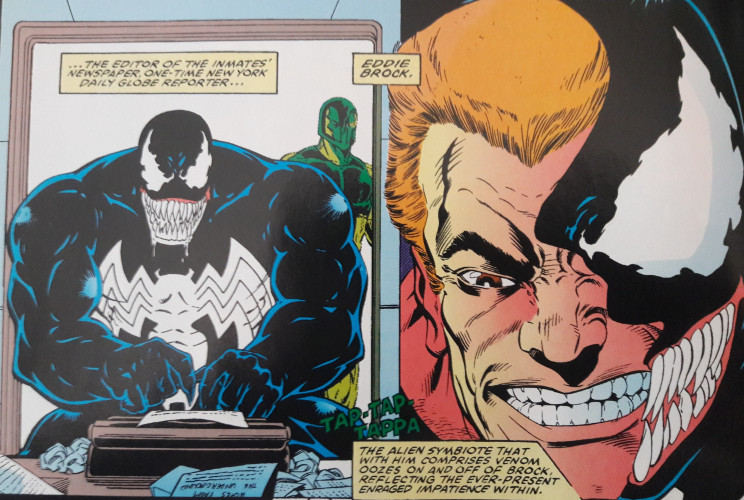

The Avengers may play the most prominent hero roles in this graphic novel (and receive top-billing in the original title), but it’s Venom who appears front-and-center. Much of the action circles around him and his attempt to break himself and fellow prisoners out of the Vault. He takes charge, assumes leadership, accepts no substitutes. The man with the lollygagging tongue and the fangs is head honcho, folks. Follow the leader or get your face not-so-surgically removed.

For those interested, this piece, though published in 1991, takes place before Venom’s successful breakout from the Vault in ASM #330, while Spidey helped the Punisher bring justice to drug-dealing U.S. army members (it’s a whole thing), thus also prior to the story where Venom stalked Peter Parker before the symbiote seemingly perished at the hands of Styx, in ASM #332-333. I was actually intrigued by Deathtrap’s chronological placement myself, as placing it in “present” day wouldn’t have made sense, as Venom was “vacationing” on a deserted island when this graphic novel was published. A bit of an aside, but I want to keep the timeline straight.

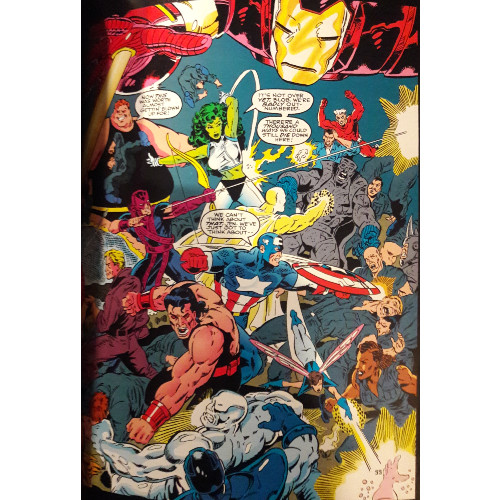

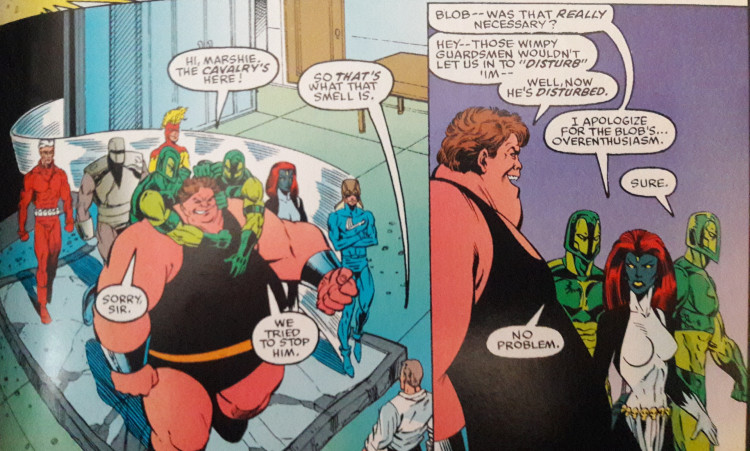

So, for now, Venom’s a prisoner leading a riot against the establishment, teaming with the likes of Electro, Radioactive Man, Moonstone, Speed Demon, Gorilla Man, Thunderball, Vapor, Orka, and Griffen. It’s a “Who’s Who” of Marvel supervillains, primarily the B- and C-grade baddies you don’t get to see quite as often. Fingeroth seems to be having fun pulling in as many random foes as he can; somewhat understandably, he constantly has characters refer to each other by their costumed identities, a tactic used, I assume, because most of these guys are wearing generic prison outfits and need to be identified in some way. I get the logic, but if I were helping free a group of supervillains, I wouldn’t be constantly identifying my holed-up homies. It seems awkward shouting "Electro!" instead of "Max!" all the time (unless you run into one of those embarrassing situations where you can't remember the guy's real identity, but you do know his supervillain name, so you keep calling him "Gibbon" because you never learned his name was "Martin Blank," which is the perfect name to either never have learned or just completely forget).

Fingeroth is at his best when he’s inserting fun, human elements into the story. He did something similar in his Deadly Foes of Spider-Man limited series, toying with characters’ personalities and motivations. He made you empathize with the Shocker, for crying out loud, the Shocker! When Fingeroth can look beyond the masks, powers, and cornball names, he includes small yet engaging character moments. Hydro Man sleeps in his cell in a literal water bed. Thunderball stands his ground against the symbiote-suited supervillain’s leadership, evidencing the brains which make him the smartest member of the Wrecking Crew. In my favorite bit, Venom, leaning into Eddie Brock’s journalistic tendencies, edits the prison newspaper, decrying the condition of the commissary. Small pieces like these make the more simplistic story surrounding the details more engaging.

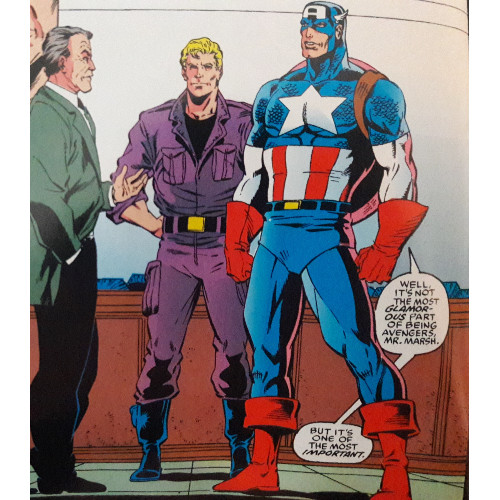

Because we’re not talking about anything deep here. Most of the tale centers around the assembled villains’ attempts to escape and the Avengers and Freedom Force’s efforts at keeping them contained. The Avengers’ inclusion makes sense–the story begins with Captain America and Hank Pym at a hearing for the Controller prior to the villain’s incarceration–but Freedom Force feels a little out of place. Made up of reformed villains once belonging to Mystique’s Brotherhood of Evil Mutants (developed by Chris Claremont and used, perhaps most famously, during “Days of Future Past”), Freedom Force is kinda “in the neighborhood” when the breakout attempt occurs, adding a slight bit of conflict when they bump into the Avengers; otherwise, this team of former villainous mutants feels shoehorned into the narrative.

Perhaps Fingeroth’s most engaging contribution to the Marvel mythos is Truman Marsh, ostensibly the Vault’s warden. Fingeroth shoves a whole page of backstory at us very quickly–Marsh’s parents were killed when he was a child, victims of superhuman combat. Fingeroth doesn’t identify what conflict this could be, and I was left scratching my head given the man’s relative age as to which of the many, many superhuman battles over the decades Fingeroth could be referencing. I initially assumed the original Human Torch/Namor skirmish, but the text clearly refers to a good/evil dynamic (and specifically mentions “teams” over individual combatants). It’s a tad vague, and may not make actual sense, but our hard-nosed warden, inspired to fight injustice in the name of his deceased parents (there's an original idea), is here to stay.

For, y’know, his only appearance ever in comic book history.

But despite the seeming inanity of his backstory, Marsh provides us a very human lens through which to read this graphic novel. Truman’s a regular dude, surrounded by bad guys who can shoot electricity, become intangible, run at the speed of sound, or bond with an alien parasite. The “dead parents” angle is supposed to not just make him relatable but gives us a reason for why he’s as tough-as-nails as he appears. At least, that’s my reasoning. The reader, I assume, is intended to develop a connection with Marsh, to understand his fanatical hatred of supervillains and tether that to his disposition as warden, but not fully agree with the less humane practices he employs later in the story. He’s hero and villain combined, someone whose personal tragedies make us wish to root for him but whose reactions to those tragedies make us wince and wonder, “Ah, Truman, if only you’d done ZYX instead of XYZ.”

My only advice, Danny? Next time, when you’re creating an everyman persona just begging for sympathy, maybe switch the parents with a wife or child. It just makes much more sense given Marsh’ age. I just can’t wrap my mind around the idea of a 50-plus-year-old man in 1991 losing his parents to a team of heroes and villains.

A tad like its namesake, Deathtrap isn’t impregnable. The security system has a couple of flaws, the commissary skimps on dessert, and the cells are a tad cramped. In spite of its issues, this graphic novel has a few foundational strengths which keep it from collapsing in on itself like Jericho. Nods and references to greater Marvel continuity are entertaining and appreciated, the warden is a surprisingly engaging central character, and the plot is amusing despite its simplicity. Between Deathtrap and Deadly Foes, Fingeroth has given us a few engaging glimpses into how the darker half of the Marvel Universe thinks and lives. As I’ve surely commented on previously, I like my villains. I love my Sinister Sixes, Brotherhoods of Evil Mutants, and Masters of Evil. But as fun as it is to see a good “hero vs. villain” smackdown or watch a superhero take on legions of lethal louses, I also enjoy character-driven narratives. I get excited about tales where your villains are treated as human beyond their fist-shaking, “I’ll get you next time!” rants or loquacious commentaries on world domination. So while Deathtrap isn’t genius, it finds its human core and toys with it nicely, offering a look behind the toothy complexion often obscuring the face of Eddie Brock and the colorful costumes of his empowered allies, even if blue jumpsuits make it a little difficult to distinguish Electro from Speed Demon.